|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

The Transition from Hominids to Hominins

Clickable terms are red on the yellow or green background |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

The

Theoretical Foundations of Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistoric

Studies |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

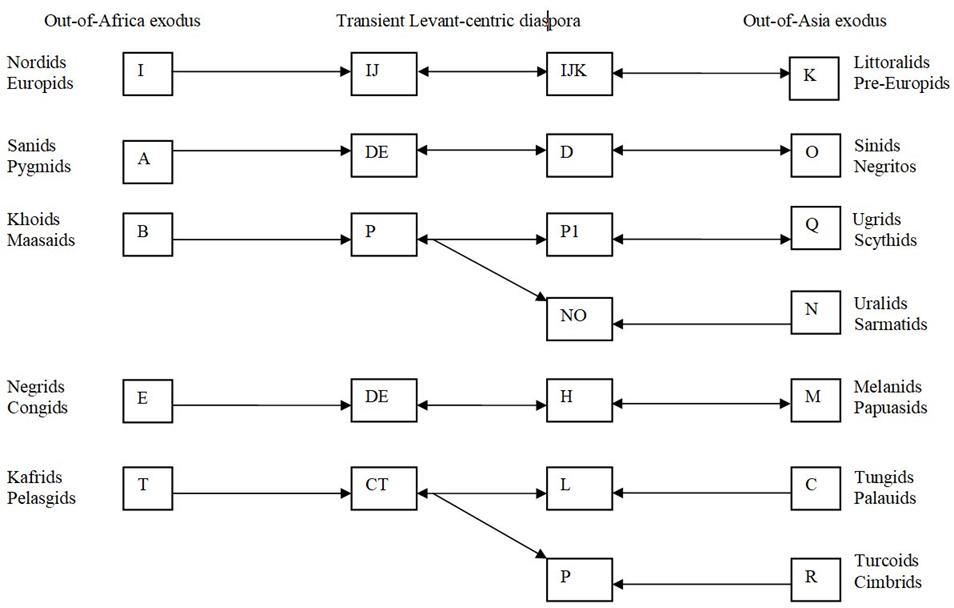

The

Transition from Hominids to Hominins

Similar lineages have to be traced up also

for hominins and recent racial varieties of humankind. The principal dichotomy

splits them into the Negritic herbivorous (pre)agriculturalists in the

tropical equatorial zone and the Altaic carnivorous (pre)pastoralists in

colder regions of Current population genetics defends African origins and Chris Stringer’s ‘single-origin model’. It supports theories

of strict monogenism in belief that one sapient race colonised the world from

one homeland in

Table 5.

The simplified genealogic tree

of Y-DNA haplogroups The out-out-Africa wandering sounds like

as tenable hypothesis but its dating must be shifted to the earlier times of

Oldowan migrations from 1.8 mya to 0.5 mya. There exists little evidence

supporting the alternative theory of an out-of-Asia model but it is worth taking into account. Besides the

Riwat flake-tool culture (2 mya) in north Pakistan it is necessary to

scrutinise Asiatic hominins as an independent genetic strain evolving

inclinations to green, yellow and red pigmentation. Asiatic orangutans and

gibbons exhibited green, grey, yellow and red hair pigmentation. Prehistoric

megalith-builders in

Table 6.

The Y-DNA transitions during the out-of-Africa and

out-of-Asia exodus Palaeontological digs are relatively rare,

so their taxonomic labels have to be determined in accordance with other

prehistoric disciplines. The categories of their diachronic phylogenesis may

be reconstructed by comparison to synchronic raceology and the ethnology of

living varieties. Another guideline is found in the typology and distribution

of archaeological cultures because their bearers were ancient anthropological

and ethnic groups. Table 6 proposes to solve their mutual correspondences and

structural resemblances like an equation in several unknowns. The evolution

of human races gets clear contours if their isolated types are arranged into

migratory chains linked by similar cultural patterns. The Balkan Dinaric race

can be related to the mythological breed of the Mycenaean Cyclopes and the

builders of Megalithic monuments in |

|

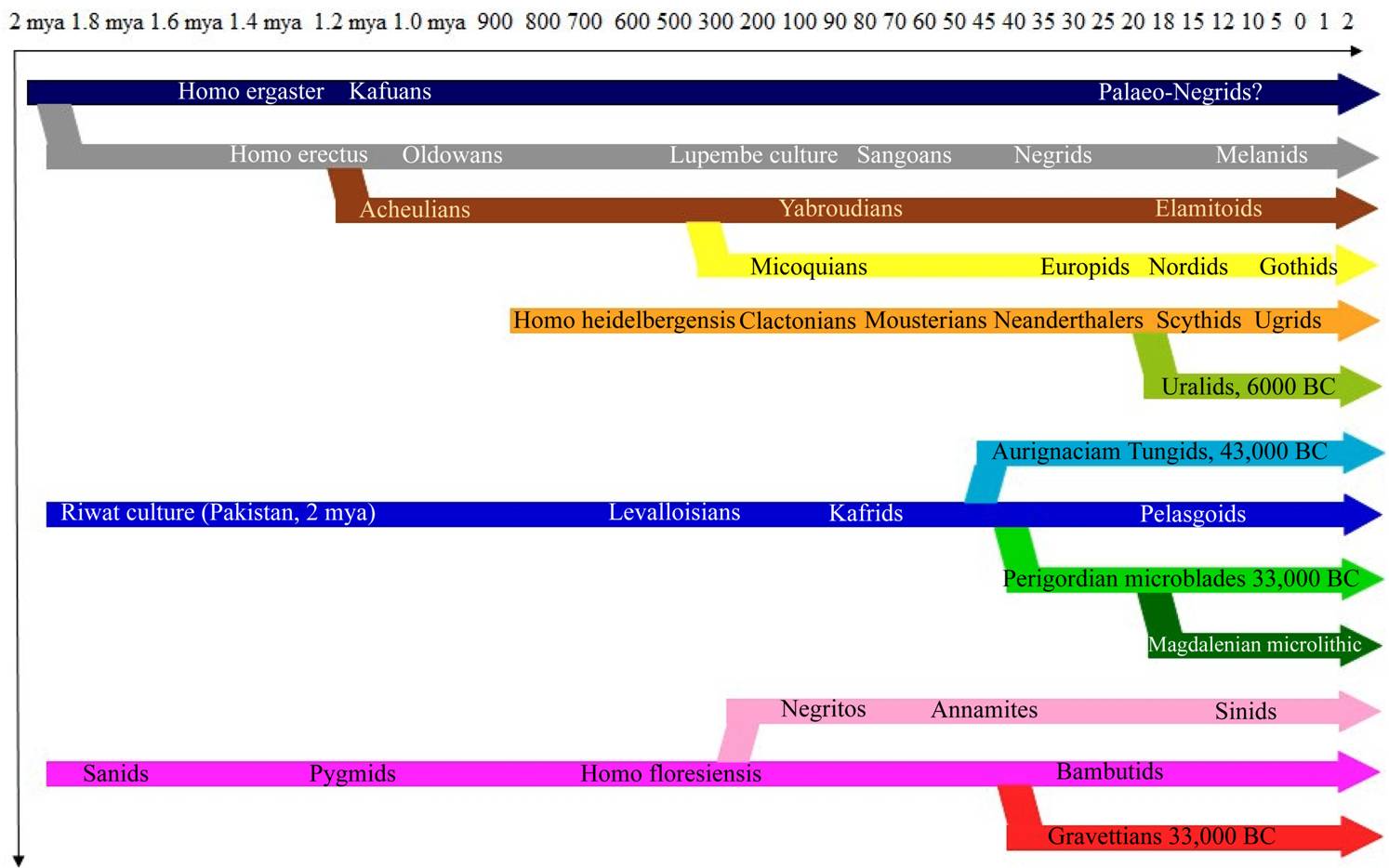

Table 7. Joint lineages of Palaeolithic and Neolithic

races Comparative parallels confirm that humans

races are not isolated local outgrowths but lawful descendant leftovers of

one prehistoric migration. Cultural comparison witnesses that African Negrids must have developed into Oceanic Melanesids,

Australids and American Amazonids. Despite certain minor differences the

South African Sanids seem to be related to Pygmies, European Lappids and

Asiatic Sinids. Leptolithic technology betrays hidden affiliation between

stocks of the Kafrids, European Pelasgids and Asiatic Tungids. Surprising

coincidences associate the African Khoids and Mousterian Neanderthalers, who

both excelled in big-game hunting, beehive architecture and manufacturing

leaf-shaped heads of lances. The most astonishing phenomenon about such

chains of prehistoric relatives appears in similarities of their language

structures.

Obvious genetic links between remote continental stocks call for an

integrated anthropological reclassification. The first hominids born in Palaeo-races, proto-races and

deutero-races formed archetypal stocks of humanity, who influenced each other

and intermarried as free genetic strains. They represented pure clear-cut

somatic taxa with definite ethnonymy, archaeological industry, religious

beliefs and cultural customs. The modern living racial groups are hardly more

than their mixed and degenerate residual derivates and have to be kept apart

as subsequent ulterior neo-races. An analogous subcategorisation has

to be carried out also in ethnology and comparative linguistics. These fields

deal only with neo-tribes and neo-languages and bury their

earlier predecessors as dead and extinct. Their real goal is to decompose

them into original pure typological elements arisen from palaeo-tribes,

palaeo-cultures and proto-languages. The Palaeolithic Survival Theory1 assumes that it is possible to

reconstruct their origins in as lawful integral genealogies as are presently

ruling in palaeoanthropology and archaeology. Such phylogenetic trees of racial varieties partly agree with

genealogies looming in population genetics. Sanids exhibited the Y-DNA

haplogroup A, the Khoids spread the Y-DNA haplogroup B, the Negrids the

haplotype E, and the Kafrids propagated the Y-DNA haplogroups T or C. DNA

haplogroups serve as an efficient tool of investigating racial interrelations

but their scope of study is confined to the last 70, 000 years. This is why

they fail to give a convincing account of earlier prehistory. Historical

linguistics is accustomed to work with ‘short-range comparisons’, while they

provide efficient methods for enquiring into ‘middle-range comparisons’

between prehistoric stocks. However, it is only archaeology and

palaeoanthropology that make it possible to plot ‘long-range genealogies’.

Generally speaking, neo-races, neo-tribes and neo-languages are only

fragmentary splinters fallen away from the mainstreams of Palaeolithic

anthropogenesis. Besides distilling into pure subcomponents they need

rearranging into regional subclades and lineages. Every Palaeolithic

palaeo-race and palaeo-tribe is an octopus spreading its tentacles radially

in several dominant directions and so their convenient subclassification

partitions racial varieties according to regional lineages. The

dominant super-lineage unites the regional outgrows of the black equatorial

races. It is fathered by its progenitor Homo erectus and its migratory

plantations should be kept together by a common taxon of Negrids or

Congids. Its continental tentacles ought to be denominated as Euro-Negrids,

Levanto-Negrids, Georgo-Negrids, Indo-Negrids, Sino-Negrids, Australo-Negrids

and Australo-Negrids. Their unity with the ancestral stock of Bantu people in

Extract from P. Bělíček::

The Synthetic Classification of Human

Phenotypes and Varieties Prague

2018, pp. 19-21 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Paragenetic Model of Human Evolution from

Hominids The paragenetic model of prehistory presupposes

that most hominins and hominids lived in relative interbreeding and their genetic

distances were much nearer than now. What we denote as detached genera and

species were actually interfertile genetic races, strains, lineages, crosses

and hybrids that later lost mutual interfertility owing to isolation in

different hominoid populations. It is not plausible that they developed by

large jumps from one genus to another, they must have maintained and

preserved their genetic pool through progressive evolutionary metamorphoses. Many

categories of genus and species were only generations, so the extant binomial

and trinomial anthropological classification should adopt a special term for

transient generations. All strains underwent parallel processes of

hominisation, gracilisation and sapientisation by means of radical

revolutions and longer stages of conservative inertia. Hominins split off

hominids and hominoids as a special genetic stream competing with alternative

strains of Paranthropines and Australopithecines. Participation in different

population strains caused intraspecial differentiation. In the following

evolutionary series the symbol means digression while the arrow → implies genetic continuity. It does not

mean direct mother-daugher inheritance but a complex statistic process with

many digressions splitting off the dominant mainstream. The following series

are chief statistic mainstreams that suggest that the Palaeolithic Urrassen

had different ancestors but converged to one of predominant Neolithic racial

varieties. Tall robust

dolichocephalous herbivores with marked crista sagittalis Gigantopithecus

(9 mya) → Ouranopithecus (9 mya) (

Gorillas (9 mya)) → Paranthropus aethiopicus

(2.5 mya) ( Paranthropus robustus (2

mya)) → Australopithecus garhi

(2.5 mya) → Australopithecus sediba (1.8 mya) → Homo gautengensis (1.8

mya) → Homo erectus

(1.8 mya) → Oldowans (1.8 mya). Slender

piscivores with tall and leptoprosopic flattish faces: Proconsul africanus (23 mya) → Kenyanthropus platyops (3.5 mya) → Australopithecus afarensis (3.9–2.9 mya) → Homo

habilis (2.1–1.5 mya) → Homo rudolfensis (2–1.5 mya) →

Levalloisians (0.5 mya). Tall

brachycephalous carnivores and big-game hunters with narrow aquiline noses Australopithecus anamensis (4.5 mya) → Laetoli man → Homo heidebergensis →

Homo rhodensis (0.5 mya) ( Saldanha

man) →

Homo neanderthalensis → Mousterians. Shortsized brachycephalous omnivores: Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4

mya) → Ardipithecus kadabba ( Pan

paniscus (Bonobo)) → Australo-pithecus afarensis (3.9 mya) → Homo habilis →

Sanids → Pygmids ( Homo floresiensis) → Sinids.

Table 1. The paragenetic model of racial

diversification |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||