|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

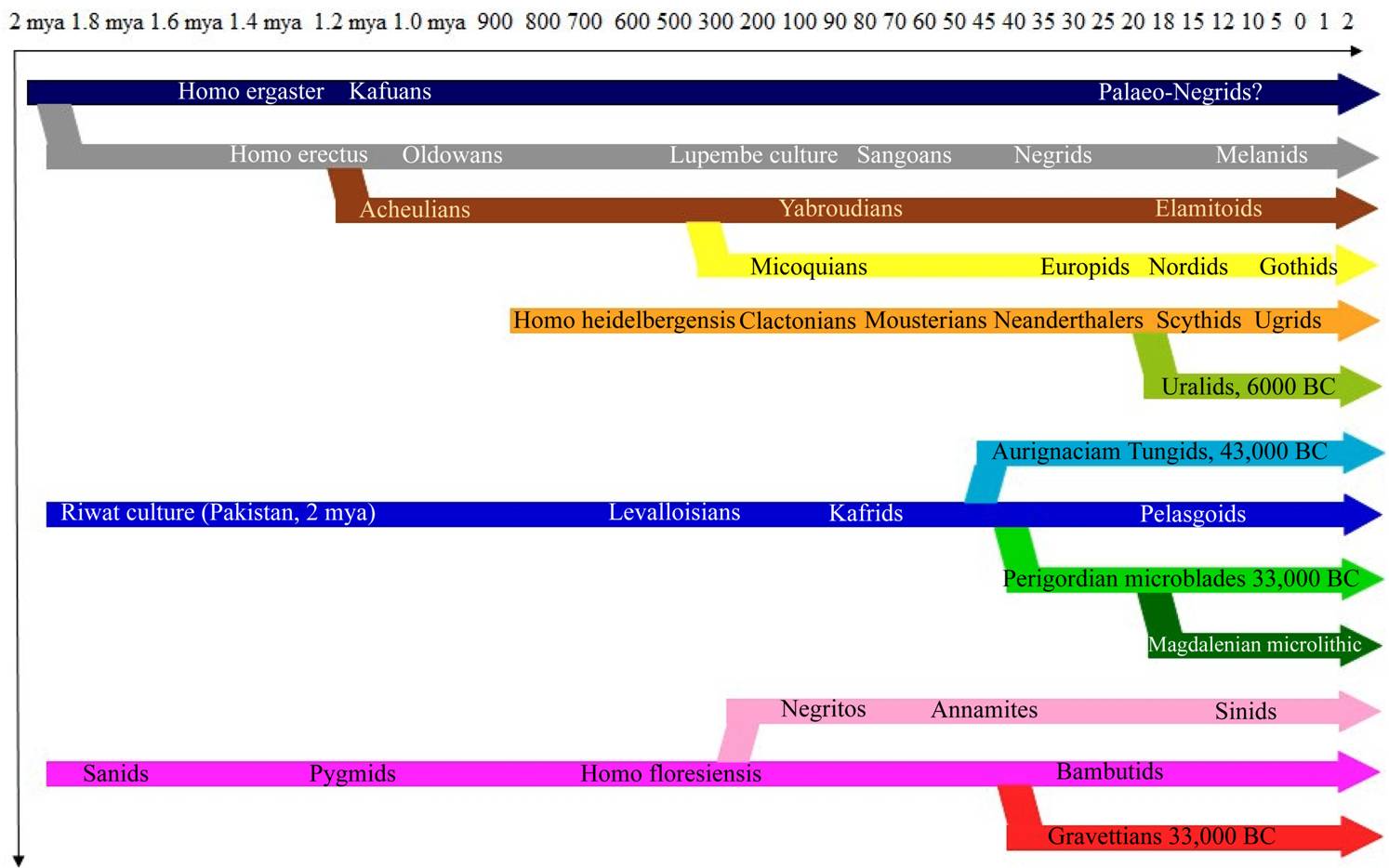

The Paragenetic

Model of Human Evolution from Hominids Clickable terms are red on the yellow or green background |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

The

Theoretical Foundations of Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistoric

Studies |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

The

Paragenetic Model of Human Evolution from Hominids The paragenetic model of prehistory presupposes

that most hominins and hominids lived in relative interbreeding and their genetic

distances were much nearer than now. What we denote as detached genera and

species were actually interfertile genetic races, strains, lineages, crosses

and hybrids that later lost mutual interfertility owing to isolation in

different hominoid populations. It is not plausible that they developed by

large jumps from one genus to another, they must have maintained and preserved

their genetic pool through progressive evolutionary metamorphoses. Many

categories of genus and species were only generations, so the extant binomial

and trinomial anthropological classification should adopt a special term for

transient generations. All strains underwent parallel processes of

hominisation, gracilisation and sapientisation by means of radical

revolutions and longer stages of conservative inertia. Hominins split off

hominids and hominoids as a special genetic stream competing with alternative

strains of Paranthropines and Australopithecines. Participation in different

population strains caused intraspecial differentiation. In the following

evolutionary series the symbol means digression while the arrow → implies genetic continuity. It does not

mean direct mother-daugher inheritance but a complex statistic process with

many digressions splitting off the dominant mainstream. The following series

are chief statistic mainstreams that suggest that the Palaeolithic Urrassen

had different ancestors but converged to one of predominant Neolithic racial

varieties. Tall robust

dolichocephalous herbivores with marked crista sagittalis Gigantopithecus

(9 mya) → Ouranopithecus (9 mya) (

Gorillas (9 mya)) → Paranthropus aethiopicus

(2.5 mya) ( Paranthropus robustus (2

mya)) → Australopithecus garhi

(2.5 mya) → Australopithecus sediba (1.8 mya) → Homo gautengensis (1.8

mya) → Homo erectus

(1.8 mya) → Oldowans (1.8 mya). Slender

piscivores with tall and leptoprosopic flattish faces: Proconsul africanus (23 mya) → Kenyanthropus platyops (3.5 mya) → Australopithecus afarensis (3.9–2.9 mya) → Homo

habilis (2.1–1.5 mya) → Homo rudolfensis (2–1.5 mya) →

Levalloisians (0.5 mya). Tall

brachycephalous carnivores and big-game hunters with narrow aquiline noses Australopithecus anamensis (4.5 mya) → Laetoli man → Homo heidebergensis →

Homo rhodensis (0.5 mya) ( Saldanha

man) →

Homo neanderthalensis → Mousterians. Shortsized brachycephalous omnivores: Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4

mya) → Ardipithecus kadabba ( Pan

paniscus (Bonobo)) → Australo-pithecus afarensis (3.9 mya) → Homo habilis →

Sanids → Pygmids ( Homo floresiensis) → Sinids.

Table 1. The paragenetic model of racial diversification |

|