|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

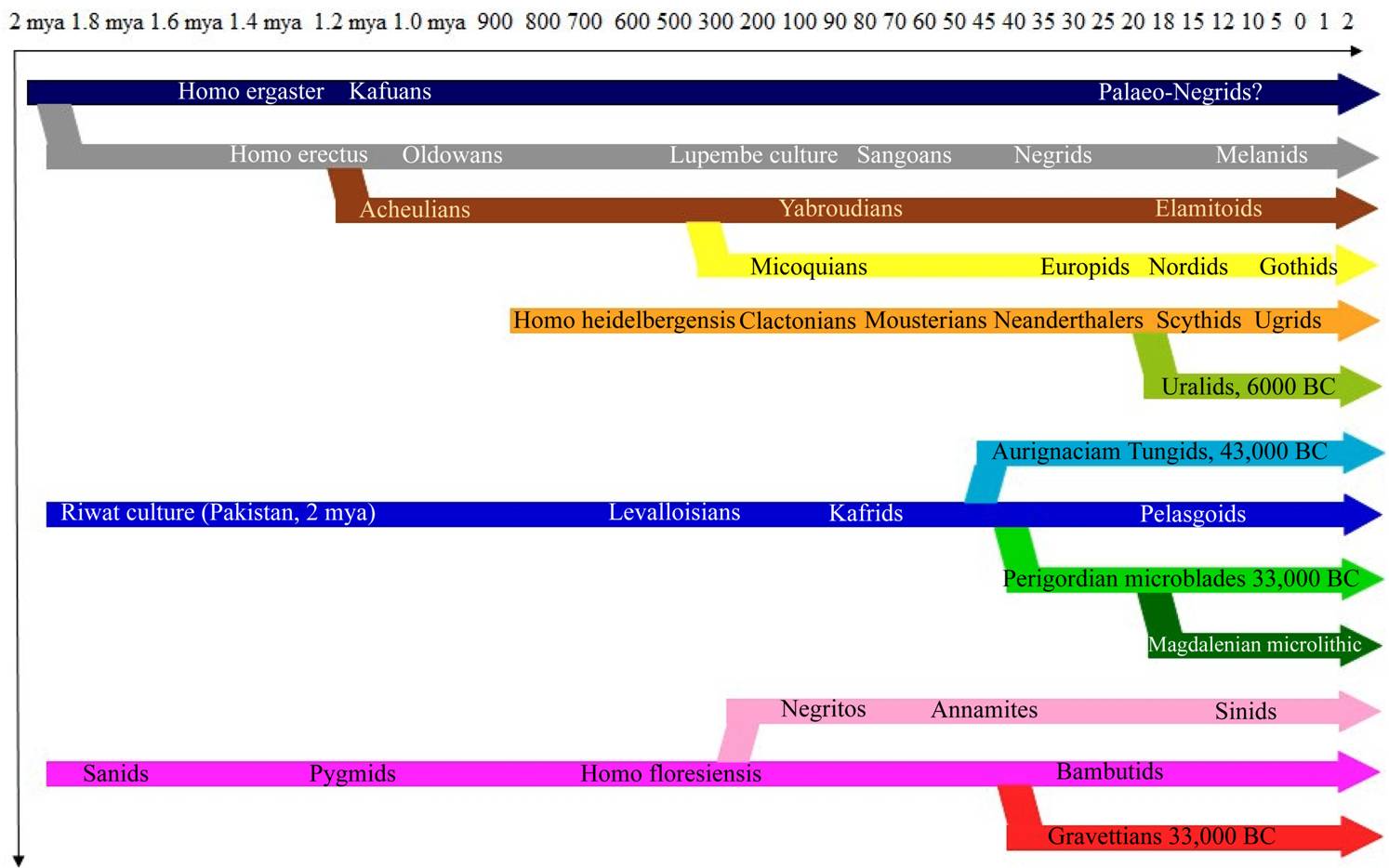

Evolutionary Paragenesis

as a Middle Way between Anthropological Monogenesis and Polynenesis Clickable terms are red on the yellow or green background |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

The

Theoretical Foundations of Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistoric

Studies |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

Evolutionary Paragenesis as a

|

|

The basic primary prototype of human species was the black ulotrichous

equatorial race, whose primary seat lay in the tropical rainforests of The most urgent theoretical requirement of

prehistoric studies is to abandon the dogmatic Extinction Theory and replace

it by the flexible accounts of Alinei’s Palaeolithic Survival Theory. It

argues that the human past is not forever dead but it continues to survive in

our blood and chromosomes. Inheritance does not jump wildly by mutations from

one genus to another but preserves all previous mutations and engenders new

subordinated varieties as its subclades. It presupposes the principle of racial interfertility2 maintained by the

so-called ring species (German Rassenkreise)3 admitting temporary mixed mating. Such ring species unite

series of early populations, which can primarily interbreed with each other

but later they fail to beget crossbreds. After a longer period of adaptive

speciation and adding new and new specific mutations they cease to be

interfertile races. Such dilemma

befell the genus of Australopithecinae, who acted as an in-between linking open-air hominins with

rain-forest hominids. Either they were pulled down into the local or regional

gene flow between neighbouring

populations or they separated from their mainstream and restored cohabitation

with the backward rainforest species. At first they coexisted as

interbreedable races but millennia of adaptive isolation made them speciate

into a diverse species and genus. Such a model of genetic mating sheds new light

on the beginnings of all hominids and hominins. It means that all binomial

designations in the genus Homo could live together as interbreedable

subspecies or racial varieties, whereas Paranthropinae and Australopithecinae

lost contact and underwent regressive mutations due to return to the

rainforest thicket. Extract from P. Bělíček: The Synthetic Classification of Human Phenotypes and

Varieties Prague 2018, p. 10-12 |

|

|

Propositions

of Evolutionary Paragenesis Reconstructions of chief human genetic

lineages lead to the following conclusions: (1) All races of

hominins were interbreedable statistic populations that survived in several

parallel genetic lineages and simultaneous tendencies. Their growth was not a

story of unilinear monogenesis but variegated multi-regional paragenesis

in several parallel lines. (2) There was no

single, unique and god’s chosen champion of sapientisation who exterminated

all alternative races of hominins. Its progress had many regional heralds,

leaders and torch-bringers. (3) Homo sapiens was

not a unique progenitor of humankind but a common evolutionary Middle

Palaeolithic stage of all hominins. Its categorial label covered most

contemporary racial varieties. (4) The assumed independent

species of the genus Homo have to be differentiated into parallel

genetic cultivars and successive evolutionary stages. Homo sapiens was

not a type-specific hominin species but an assimilative phase of most (5) Long-range anthropic

markers (racial phenotypes, folk architecture, clothing style, totemistic

cults) demonstrate that there were no extinct races of hominins that fell

victim to the predatory fads of one victorious sapiensator. There were only

regional minorities absorbed by more advanced populations. (6) The evolutionary

processes of hominisation, sapientisation and gracilisation affected all

genetic lineages of hominids and hominins in equal rates but proceeded at

faster pace in cultural centres and at slower speed in peripheral isolation

(in insular colonies, exotic paradises and rainforest thickets). (7) Anthropopithecinae

could pursue two alternative fates. In open-air centres they integrated as a

subvariety of the genus Homo, in rainforest thickets their progressive

evolution lapsed into regressive devolution and converged to integration with lower apes. (8)

Speciation usually terminated progressive evolution and resulted into a phase

of genetic stagnation. (9) The immigrants in the

Levantine centre mostly promoted and accelerated their genetic potential,

while Australian colonists underwent degenerative changes in contact with

isolated local aborigines. (10) What we discuss as the

alleged independent hominins species were actually intermarriageable human

varieties that lost interfertility and became independent species only later

by isolative speciation. (11) The archaeological

complexes of Oldowans, Clactonians, Mousterians, Denisovans and Acheuleans

did not die out but survived in the living racial varieties of

humankind. (12) The monistic philosophy

of anthropological thought teaches to unite all accessible racial, ethnic,

linguistic, religious and archaeological evidence and treat human varieties

in one integrated whole. Extract

from P. Bělíček: The Synthetic Classification of Human Phenotypes and

Varieties Prague 2018, pp.

22-23 |

|

Arguments for Evolutionary

Paragenesis * The black equatorial race was principally

opposed to the Asiatic or Altaic races living in the boreal zone of Eurasia.

The beginnings were probably shaped in the colder temperate regions of South

Africa. Their earliest antecessors Homo rudolfensis, Homo habilis

and Homo heidelbergensis look like hypothetical taxa but they are

embodied in the surviving racial varieties of the lake-dwelling Kafrids of

East Africa and the cattle-breeding nationality of Khoekhoe Khoids. The

latter group is now restrained only to arid regions of Kalahari Desert but

its residual vestiges can be traced up also in the cupolar beehive huts

typical of their clansmen all over the world. * About 500,000 years ago Homo habilis

emerged in Eurasia as a live carrier of the Levalloisan flake-tool culture.

Archaeologists grudge it the status of an autonomous self-contained

archaeological complex but its spread from * Homo denisoviensis

is now classified as a close relative of classic Neanderthals and dubbed also

as Homo

altaiensis (Altai man) or Homo siberiensis ‘Siberian man’. John D. Croft’s model (Map 1) assumes that

they both descended from Homo heidebergensis drifting from * The prehistoric travels of

Altaic races are hard to discern because they buried their dead by exposition

on the scaffolding or by drowning their corpse in deep waters. Their

religious creeds hindered them from interring their bodies by inhumation in

the earth because their souls had to be sent out on a long travel to a faraway underworld called Tartarus. * The Pygmids and

Lappids disappeared from the sight of palaeoanthropologists on account of

different reasons. They buried their dead forefathers by cremation, carried

their burnt ashes in grass-woven bags and scattered them in rainforest

solitude. The only probable migrations of their stock were the Negrito

diaspora about 62,000 BP in Extract from P. Bělíček: The Synthetic Classification of Human Phenotypes and

Varieties Prague 2018, pp. 22-23 |

|

|

The

Paragenetic Model of Human Evolution from Hominids The paragenetic model of prehistory presupposes

that most hominins and hominids lived in relative interbreeding and their genetic

distances were much nearer than now. What we denote as detached genera and

species were actually interfertile genetic races, strains, lineages, crosses

and hybrids that later lost mutual interfertility owing to isolation in

different hominoid populations. It is not plausible that they developed by

large jumps from one genus to another, they must have maintained and

preserved their genetic pool through progressive evolutionary metamorphoses. Many

categories of genus and species were only generations, so the extant binomial

and trinomial anthropological classification should adopt a special term for

transient generations. All strains underwent parallel processes of

hominisation, gracilisation and sapientisation by means of radical

revolutions and longer stages of conservative inertia. Hominins split off

hominids and hominoids as a special genetic stream competing with alternative

strains of Paranthropines and Australopithecines. Participation in different

population strains caused intraspecial differentiation. In the following

evolutionary series the symbol means digression while the arrow → implies genetic continuity. It does not

mean direct mother-daugher inheritance but a complex statistic process with

many digressions splitting off the dominant mainstream. The following series

are chief statistic mainstreams that suggest that the Palaeolithic Urrassen

had different ancestors but converged to one of predominant Neolithic racial

varieties. Tall robust

dolichocephalous herbivores with marked crista sagittalis Gigantopithecus

(9 mya) → Ouranopithecus (9 mya) (

Gorillas (9 mya)) → Paranthropus aethiopicus

(2.5 mya) ( Paranthropus robustus (2

mya)) → Australopithecus garhi

(2.5 mya) → Australopithecus sediba (1.8 mya) → Homo gautengensis (1.8

mya) → Homo erectus

(1.8 mya) → Oldowans (1.8 mya). Slender

piscivores with tall and leptoprosopic flattish faces: Proconsul africanus (23 mya) → Kenyanthropus platyops (3.5 mya) → Australopithecus afarensis (3.9–2.9 mya) → Homo

habilis (2.1–1.5 mya) → Homo rudolfensis (2–1.5 mya) →

Levalloisians (0.5 mya). Tall

brachycephalous carnivores and big-game hunters with narrow aquiline noses Australopithecus anamensis (4.5 mya) → Laetoli man → Homo heidebergensis →

Homo rhodensis (0.5 mya) ( Saldanha

man) →

Homo neanderthalensis → Mousterians. Shortsized brachycephalous omnivores: Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4

mya) → Ardipithecus kadabba ( Pan

paniscus (Bonobo)) → Australo-pithecus afarensis (3.9 mya) → Homo habilis →

Sanids → Pygmids ( Homo floresiensis) → Sinids.

Table 1. The paragenetic model of racial

diversification |

|

||