|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

The Folktale Typology of

Prehistoric Races

Clickable terms are red on the yellow or green background |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

The

Theoretical Foundations of Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistoric

Studies |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

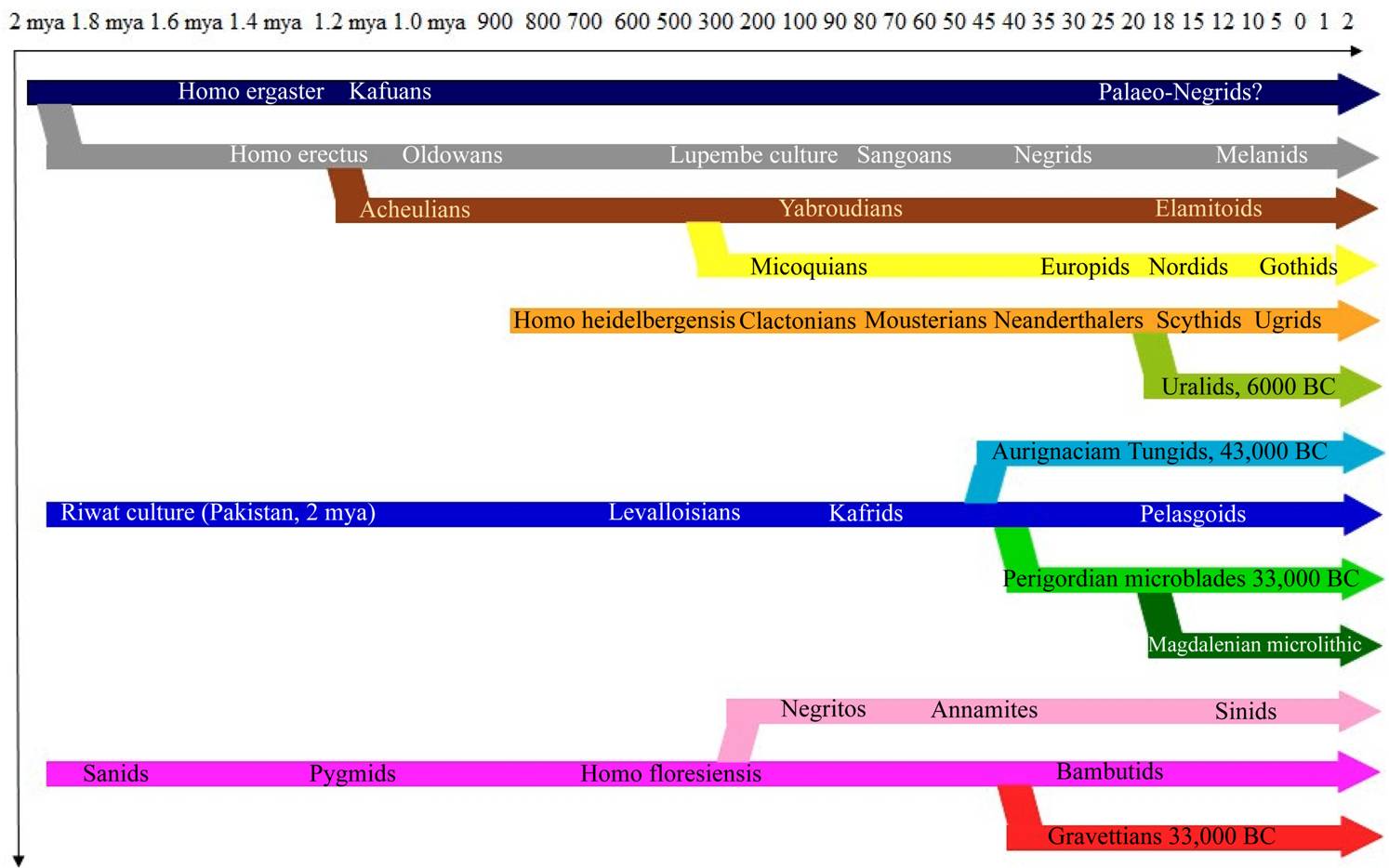

The

Paragenetic Model of Human Evolution from Hominids The paragenetic model of prehistory presupposes

that most hominins and hominids lived in relative interbreeding and their genetic

distances were much nearer than now. What we denote as detached genera and

species were actually interfertile genetic races, strains, lineages, crosses

and hybrids that later lost mutual interfertility owing to isolation in

different hominoid populations. It is not plausible that they developed by

large jumps from one genus to another, they must have maintained and

preserved their genetic pool through progressive evolutionary metamorphoses. Many

categories of genus and species were only generations, so the extant binomial

and trinomial anthropological classification should adopt a special term for

transient generations. All strains underwent parallel processes of

hominisation, gracilisation and sapientisation by means of radical

revolutions and longer stages of conservative inertia. Hominins split off

hominids and hominoids as a special genetic stream competing with alternative

strains of Paranthropines and Australopithecines. Participation in different

population strains caused intraspecial differentiation. In the following

evolutionary series the symbol means digression while the arrow → implies genetic continuity. It does not

mean direct mother-daugher inheritance but a complex statistic process with

many digressions splitting off the dominant mainstream. The following series

are chief statistic mainstreams that suggest that the Palaeolithic Urrassen

had different ancestors but converged to one of predominant Neolithic racial

varieties. Tall robust

dolichocephalous herbivores with marked crista sagittalis Gigantopithecus

(9 mya) → Ouranopithecus (9 mya) (

Gorillas (9 mya)) → Paranthropus aethiopicus

(2.5 mya) ( Paranthropus robustus (2

mya)) → Australopithecus garhi

(2.5 mya) → Australopithecus sediba (1.8 mya) → Homo gautengensis (1.8

mya) → Homo erectus

(1.8 mya) → Oldowans (1.8 mya). Slender

piscivores with tall and leptoprosopic flattish faces: Proconsul africanus (23 mya) → Kenyanthropus platyops (3.5 mya) → Australopithecus afarensis (3.9–2.9 mya) → Homo

habilis (2.1–1.5 mya) → Homo rudolfensis (2–1.5 mya) →

Levalloisians (0.5 mya). Tall

brachycephalous carnivores and big-game hunters with narrow aquiline noses Australopithecus anamensis (4.5 mya) → Laetoli man → Homo heidebergensis →

Homo rhodensis (0.5 mya) ( Saldanha

man) →

Homo neanderthalensis → Mousterians. Shortsized brachycephalous omnivores: Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4

mya) → Ardipithecus kadabba ( Pan

paniscus (Bonobo)) → Australo-pithecus afarensis (3.9 mya) → Homo habilis →

Sanids → Pygmids ( Homo floresiensis) → Sinids.

Table 1. The paragenetic model of racial

diversification |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Folktale Typology of Prehistoric Races

The great import

of popular folktales to systematic racial taxonomy consists in an explicit

testimony and identification of the source-to-target ethnic perspective.

Prehistoric lore anticipated the science of modern anthropology by sketching

a sort of fantastic monsterology that

perceived foreign tribes as unnatural beings. Considering their types from

the viewpoint of modern narratology, we should speak of a field of

comparative fictional characterology as a discipline giving natural

anthropological interpretations to superstitious fictions. Our prehistoric

forebears viewed Lappids as tiny elves and dwarfs, giant Basco-Ugrids as

cannibalic ogres, Turcoid cave-dwellers and pirates as dragons, Sarmatoid

raiders as lycanthropic werewolves and vampires and tall Nordic Goths as lazy silly Jacks.

Foreign warriors were feared as animal monsters because they made raids in

totemistic disguise. Every prehistoric

race had its own specific animal heroes, feared inimical predators and folktale

types. Animal trickster tales indulged in elfin heroes and can be

described by a simple formula: ‘an elfin animal hero outwits a silly giant

animal’. In ogrish tales the central monstrous figure is the ogre or

ogress conceived as an unnatural being with cannibalistic dispositions.

However, their narrative perspective fulfils the formula ‘en elfin girl

escapes the threat of devouring by an ogrish cannibal’, so their more

accurate name should read ‘anti-ogrish tales’. If we clean the story of The

Little Red Riding-Hood of improper later associations with horse-riding

sports, it may be seen as an elfin-to-lycanthrope archetype as red hoods were

peculiar to fairy-tale dwarfs and medieval coxcombs, while lycanthropy and

wolfine totemism pertained to beliefs of Sarmatian raiders. It simply

described the social clashes of the autochthonous Alpines besieged by

assaults of Hallstattian invaders of Sarmatian origin. Tales about ogres form the most core of

narratives denoted as fairy tales. Fairies are usually described as

supernatural beings that lure humans to follow them to water depths or to

forest thickets. Their appearance and social customs differed according to

sex, age and degree of civilisation. Their majority belonged to female

forestial or waterside creatures as their folktale motifs referred to women

who sojourned in caves and later in waterside hill forts. They were built on

inaccessible high rocky promontories towering over river streams and

mentioned in folktales as wizards’ castles. Their ramparts served as a winter

base for herdsmen, who departed every spring with their herds of cattle and

grazed them in mountainous pastures over summer. During their spring

expeditions they dwelt in light portable tents, while their wives and kids

lived on a limited supply provided by the animal and human catch.

Table 9.

Supernatural beings and ethnic stocks in European folktales |

Their tribal identity can be

deciphered easily from their monsterological description drafted out in

tales. The supernatural creatures of the Slavonic fairies rusalka, jezinka or yezinka, mara or Genuine fairy tales concerned

only nymphs and fairies that seemed to be the least dangerous of the whole

band. Their festival Walpurgisnacht was celebrated by nightly dances

in Lycanthropic myths mention a number of typical Uralian and Sarmatian

customs: lupine totem cults, night-time looting raids upon rural communities,

wearing masks made of wolfish heads and furs, blood-letting and

blood-sipping, impaling enemies on stakes or posts of palisades, killing them

by stabbing their heart with a wooden pole etc. Moreover, the folklore of

Sarmatian male warriors included drinking intoxicating beverages (kumys,

ale, Vedic soma, Iranian haoma), tossing bones and dice for

scapulomantic divination, reciting heroic sagas and songs with the accompaniment

of string instruments. Their festivals were remarkable for sword dances

called Morisken-tanz in At the stage of Mesolithic

hunters the Uralian and Sarmatian tribes spent severe winters in waterproof

caves. Their shelter was peculiar also to fairies yezinkas in the Slavonic

tales about the little Rosin-boy.1 They besought him to open the door because of severe frost, and when he

took mercy on them, they kidnapped him away from his guardian stag’s abode.

They featured as miserable man-eating cannibalistic beings living as

ogresses. One related type of the ogresses yezinkas looked like the

old hag Baba Yaga dwelling in a hut on chicken feet, which was a clear

hint at waterside post-dwellings of Tungusoid fishermen’s tribes. Such

ogresses must have led a sad lonely life in the wilderness like hermits. When

Altaic tribes had to spend a severe cold winter in starvation, they used to

oust the over-aged elders from their home and sent them to die alone in the

woods. Such forms of forcible or voluntary hermitage made these retirees

improve their poor bill of fare by kidnapping children that had gone astray

in the forest and roast them in the oven.

Unnatural cannibalistic

practices in ogrish tales had a natural explanation in

savage hunters’ life. Every folktale type had a male, female and juvenile

version telling a different story. Warriors, women and children looked at

their clan’s ritual practices from a different angle of view but participated

in one collective economic process of tribal subsistence. Folkloristic

analysis of folktales must see through diverse viewpoints, put together seeming

inseparables and integrate alternative versions into one common type of

fabulas. After removing inorganic

later additions and generalising local mutations it is possible to reveal the

common prehistoric core. Scythoid big-game hunters tended to worship a feline

totem but their colonists adapted its appearance to local species of feline

beasts of prey. African megalith-builders prayed to lions and sphinges, their

Asiatic relatives to tigers (weretigers) and Quechuan megalith clans in Extract from P. Bělíček: The Synthetic Classification of Human Phenotypes and Varieties Prague 2018, p. 25-27 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||