|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

Ancient Amerindian Indigenous Architecture Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

|

|||||||

|

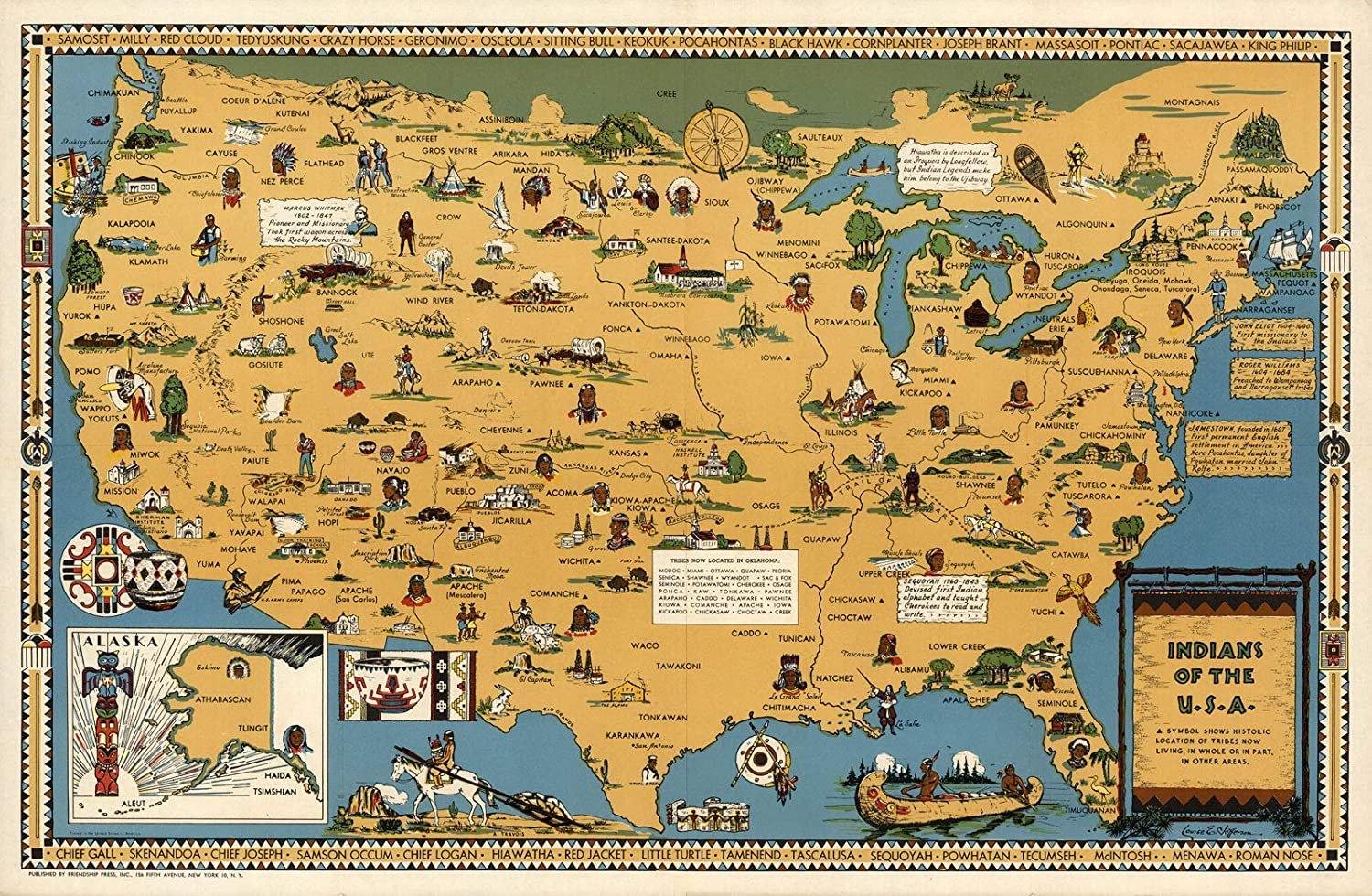

Map 1. Types of American Indian

Indigenous Dwellings |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Map 2. American

Indian housing and clothing |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

GENERAL ARCHITECTONICS

|

FOLK ARCHITECTURE § Cliff-Dwellings and Burial Rock-Cut Caves

§ Rectangular

Longhouses Out of Straw and Mud

§

Earth

lodges and Subterranean Sancturaries § Semidugout Zemlyankas of Lapponoid Cremators

|

TYPES OF DWELLINGS

§

Tungusoid teepes, pile-huts and lake-dwellings

§ Pelasgoid conical rondavel roundhouses§

Megara, palatial temples

and columnal palaces

§

Flat-roofed

labyrinth architecture of Oriental farmers

§

Rectangular wicker longhouses with

thatched roofs

§

Gotho-Frisian

wurts, terps and half-timber longhouses

§

Dome-shaped

beehive huts

§

Irregular

multi-peaked marquee nomadic tents

·

Epi-Aurignacian tepees and pile-dwellings

·

Bascoid Cyclopean megalithic

architecture

· Megalithic

tombstones and tholoi graves

·

Lapponoids’ lean-to and semidugout pit-house

·

Turcoid

dwellings and burials in rockcut caves

|

ANCIENT SETTLEMENTS §

Lakeland,

marshland, lowland, grassland and desert ecosystems §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites

in oases of subtropical shrublands §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites in

oases of subtropical shrublands §

Oppidans:

hillforts towering on high rock promontories §

Getic boroughs:

villages in alluvial lowlands §

Palatial poleis

and cultic spas in seaside harbours §

Straight streets and

alleys of lake-dwellings |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

The Architecture

of Traditional Indigenous

Houses Man

protects himself from adversities of the weather and climate in different

geographic zones by dwellings. If ABO groups represent a trans-species

phenomenon uniting humans with primates, dwellings, surprisingly, provide a

trans-continental criterion of comparison. Their patterns seem to be ‘trans-chronical’

because architectural archetypes seem to have persisted since Palaeolithic

times up to now and modern indigenes. For instance, dome-shaped beehive

dwellings unite Swazi people, Khoids, Maasai tribes, Berber and Basque

funeral architecture, Irish or Scottish megalith-builders, Algonquian

wigwams and Peruvian Quechua habitations. Their origin from Mousterians is

demonstrated by Molodovo mammoth-bone huts and Eskimo whale-bone huts in

Greenland. Mutual differences were removed by cave dwellings occupied by

boreal hunters in wintertime. The following ordered chains do not sketch

direct transitions but suggest stages that apply also to parallelisms in

premortal and postmortal abodes: straw beehive hut

> stone clochán and cairn > cupolar mosque

dome > citadel; Khoisan

heap-stone tomb > Berber tumulus > Mycenaean tholos >

pyramid; post-dwelling

> rondavel roundhouse > conical tepee > columnal palace; collective oblong longhouse >

Amazonian maloca > Gothic half-timber wurt. They demonstrate that evolution does not

switch from one typological archetype to another but observes laws of

inheritance that preserve genetic continuity pursuing one characteristic

tradition. Such continuity links prehistoric tents with medieval folk huts

and royal residences of monumental architecture. This means that cultural

development proceeds forth in several independent lineages along different

paths. Table 1 employs square brackets for tribal groups so as to indicate

ethnic appurtenance.

Table 1. Types of huts and

dwellings |

Architectural

Taxonomy An alternative model of architectonic

classification may be submitted to consideration in Table 2. Its disadvantage

is seen in too many neologisms, great complexity and divergence from standard

conventions. Its specific trait consists in applying local terms as

archetypes for entire classes of similar buildings. If it displays a positive

feature worth pursuing, it is a series of compound words ending in -tectonic.

It indicates that the actual reference cocerns the systematic typology of

constructions in popular huts and folk architecture. They show that folk

architecture builds a bridge over the wide abyss between Palaeolithic and

Eneolithic morphology and disclose their structural continuity from times

immemorial.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Auxiliary

Criteria of Architectural and Ceramic Ethnology

The racial and ethnic identification cannot

be guided only by the present-day phenotype appearance, its analysis has to trace

back archaeological roots, explore geographical distribution and compare also

typological chains in several prehistoric disciplines. Map 4 demonstrates

that Africa is occupied by at least three related dolichocephalous racial

stocks with similar osteology, craniology and housing: autochthonous African

Negrids, Caucasoid Ethiopids and Nordic Littorids. Their skeletons show tall

stature, platycnemia betraying terrestial open-air ecotype and upright gait

but share similar traits also in collective life-style, clothing,

architecture and housing. Moreover, they seem to be correlated also by

analogous inclinations to axe-tool making industry, vegetal and

plant-gathering subsistence, rectangular longhouses, matrilocal endogamous

marriage, dowry and theocracy. Map 4 shows three principal streams of

axe-tool makers, who descended from the African continent but later returned

back to its heart. All factions of Negrids originally cohabited in large

matrilinear families and built quadrangular timber huts filled by clay. Their

shape was roughly similar to large longhouses inhabited by the Danubian

peasants of the Neolithic Linear Culture or collective house maloca of

the Tupí-Guaraní tribes in Amazonia. The common denominator of all Negrids

consisted in wearing fringed grass aprons and the custom of grown-up women to

go out bare-breasted in a topless dress. Fringed grass aprons form an

indispensable accessory of clothing in Melanesia, Polynesia and Amazonia.

Their design was clearly discernible also in paintings of ancient

Mesopotamian Gutii, ‘Ubaidan

peasants and Cretan goddesses. The chief duty of their females was to bring

water in gouged wooden vessels on their head. Another typical utensil was a

head-bench for resting and sleeping. External influences from Eurasia were

visible in Caucasoid Etiopids and Atlantic Littorids. The Acheulean Ethiopids

accomplished an architectural revolution by replacing wooden logs by clay and

rammed pisé on account of lack wood in arid desert regions. They began

to build multi-cellular many-roomed houses out of sun-dried bricks. They had

flat roofs, firm external walls and few outer windows. In fear of alien

intruders, they were usually accessed on removable ladders from above. Their

architectonic style was favoured by farmers and townsfolk in Ethiopia, Egypt,

Libya and Algeria. The hybrid composition of African Nordids and Caucasoids

out of heterogeneous layers should not make us blind to their specific new

peculiarities. Their ethnic heritage shone through especially in the rites of

bull cults and bull fighting. They settled down in fertile areas along the

reaches of water streams but they did not despise colonising arid areas of

oases in deserts, either. The last but not the least of African

races comes the ethnic group of white-skinned Littoralids pursuing the

western coast of Africa as beachcombers as far as the South African Cap of

Good Hope. The European Bell-Beaker Folk and

African Littoralids manufactured campaniform pottery with corded patterns and

lived in huts that were reminiscent of the Frisian three-aisled wurt.

Their two-pitched roofs were sloping down to the earth. The mysterious

group of Atlantic Littoralids with shell midden evolved from the Mesolithic

Campignian culture (10,000 BC). They were of Indo-European origin but

differed from the Danubian Europids with clear agricultural dispositions by

living as shellfish eaters relishing on molluscs, snails and frogs. These

northern invaders were probably responsible for the import of the West

African sacred double-bitted axe. The ancient Romans knew it as bipennis, the Greek

Minoans called it labrys and Lydians mentioned it as

πελεκυς, pelekus.1 Its true copy was celebrated in the

mythology of African Yoruba people, who worshipped it as a symbol of the god

Sango or Xango. The early invasion of white-skinned Nordids into the African continent can be documented also by archaeological finds. Their hosts sailed along the western coasts of Portugal, Mauretania, Guinea and Angola as far as South Africa. They belonged to beachcombers classified as Littoralids, built their shelters on elevated sand-dunes and left behind characteristic heaps of shell midden (kjökkenmöddinger). Their roaming hordes may be denoted as Campignians affiliated to Frisians and the Mugem culture in Portugal. The southwest regions of Europe became their secondary homeland and served as the birthplace of Franco-Swabian tribes. In the Neolithic they developed a special cultivar of the Beaker-Folk culture with its typical bell-shaped pottery. It was probably the Portuguese Mugem shell-midden culture that ensured Frenchmen and Franco-Swabians the ill repute of frog-eaters. The ceramic morphology of the Spanish Bell-Beaker Folk retained its patterns also on African travels. It breathed life into the Campagniforme culture swaying in Guinea and Angola in the Neolithic period. Its spread may be responsible for a great number of Europoid toponyms and ethnonyms such as Cotonou, Ketou, Brass and Sasso in the Gulf of Guinea. The residual vestiges of the Bell-Beaker Folk Littoralid’s colonies can be recognised also in recent ethnic tribes. Bernartzik’s ethnographical survey mentioned them as hosts of conspicuously white-skinned indigenous tribes on the coasts of Angola.2 |

Such intercontinental similarities witness

that consanguine populations maintain genetic inheritance, cultural endurance

and long-range typological stability. Their inner affinity is based on the common

genetic outfit passed as a relay over hundred thousand years. After Negrids

pursued the fates of archaic Oldowan ancestrors they enriched their cultural

endowment by adding Sangoan and Lupembian innovations. On the Arabian

Peninsula they infiltrated into the northern boreal Asiatic races and their

mutual contacts gave rise to the mixed hybrid race of Acheulean Caucasoids.

Caucasoids flooded the Near East, Anatolia and South Asia and took part in

reforms of Neolithic agriculture. Their kinsfolk expanded also backwards in

the native African continent and created a new racial variety of Ethiopids.

Their northern mutations included European Neolithic farmers and Campignian

Littoralids, who combed the beaches of Atlantic seacoasts as far as the Gulf

of Guinea. Map 5 adds comparison between rectangular

housing types common to axe-tool cultures of African origin and tent

constructions characteristic of Afro-Asiatic tribes descending from the Near

East. The raids of Afro-Asiatic invaders are assumed to have created the

language families of Semitic,

Berber, Chadic, Cushitic, Egyptian and Omotic peoples.

The Arabic and Bedouin nomadic camel-breeders lived in irregular marquee

tents with several pitches supported by poles. Bedouins called them beit

al-sha’r, its Mauritanian form was denoted as tekna

and Tibetan herders knew it as ndrogba. The

Berber Imazhigen originally built huts and burials mounds resembling cupolar

or half-barrel shaped beehive constructions common among the Maasai and the

Khoisan Khoikhoi. But they looked like stonemade dome-shaped vaulted cairns,

whereas the cattle-breeding herders in the southern regions of Africa made

them out of boughs and straw. Cushitic settlers took over the architectonic

style of East African rondavels, i.e. the Pedi-Thongan roundhouses

with pointed conical roofs and cylindrical basement. Modern Herero and Damara

tribes live in conical huts with cylindrical understructure but their

Mesolithic progenitors preferred to dwell in rock shelters and articifical

rock-hewn-caves. They arrived to South Africa with the plantations of Wilton

culture colonists (5000 BC) and sketched petroglyphs and rock-paintings that

are erroneously attributed to Bushmen.

From Pavel Bělíček: The Differential Analysis of the Wordwide Human Varieties . Prague 2019. pp. 14-17 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||