|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

The Ancient Indigenous Architecture of Microlithic TribesClickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

|

||||||||

|

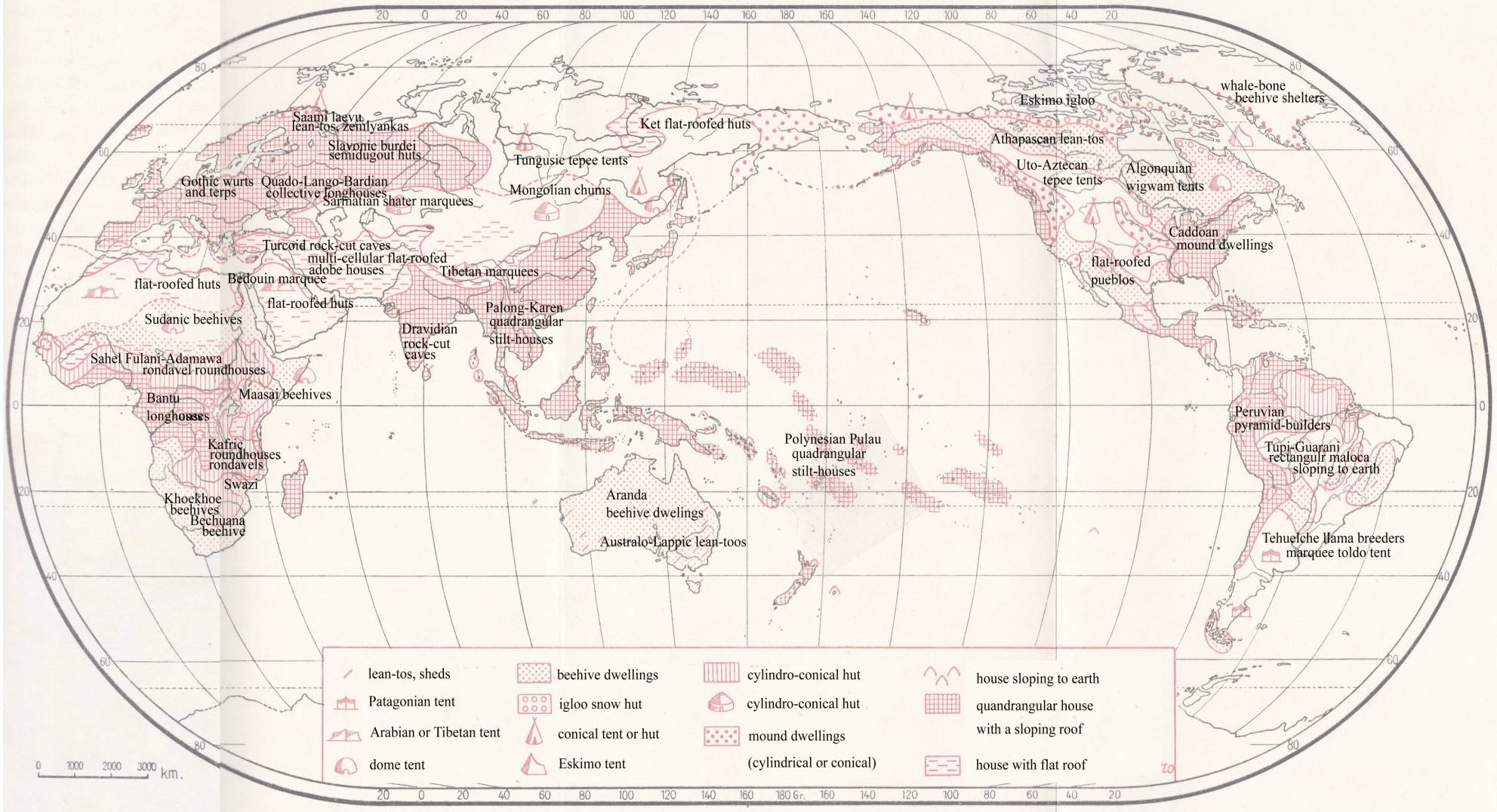

Map 1. Types of human dwellings (after R.

Biasutti) |

||||

|

|

||||

GENERAL ARCHITECTONICS

|

FOLK ARCHITECTURE § Cliff-Dwellings and Burial Rock-Cut Caves

§ Rectangular

Longhouses Out of Straw and Mud

§

Earth

lodges and Subterranean Sancturaries § Semidugout Zemlyankas of Lapponoid Cremators

|

TYPES OF DWELLINGS

§

Tungusoid teepes,

pile-huts and lake-dwellings

§ Pelasgoid conical rondavel roundhouses§

Megara, palatial

temples and columnal palaces

§

Flat-roofed

labyrinth architecture of Oriental farmers

§

Rectangular wicker longhouses with

thatched roofs

§

Gotho-Frisian

wurts, terps and half-timber longhouses

§

Dome-shaped beehive huts

§

Irregular

multi-peaked marquee nomadic tents

·

Epi-Aurignacian

tepees and pile-dwellings

·

Bascoid Cyclopean megalithic

architecture

·

Megalithic

tombstones and tholoi graves

·

Lapponoids’ lean-to and semidugout pit-house

·

Turcoid dwellings

and burials in rockcut caves

|

ANCIENT SETTLEMENTS §

Lakeland,

marshland, lowland, grassland and desert ecosystems §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites

in oases of subtropical shrublands §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites in

oases of subtropical shrublands §

Oppidans:

hillforts towering on high rock promontories §

Getic boroughs:

villages in alluvial lowlands §

Palatial poleis

and cultic spas in seaside harbours §

Straight streets

and alleys of lake-dwellings |

|

Cliff-Dwellings and Burial Rock-Cut Caves

Argillae. The Cimmerian cliff-dwellings were dugouts and

souterrains cut into cliffs. They appeared in misty regions veiled in gloomy

clouds and dense fog where the sun never shone and never showed its face.

Ephoros, himself a native from Cyme in Asia Minor, attributed Cumae in

Italy to the Cimmerians. He explained that their permanent homes were in

rock-cut subterraneans called argillae. In deep subterranean caves

they had oracles and priests who never saw the sun and were allowed to go out

only at night. They drank water from a well at the bottom of their

subterranean temple. They believed that it was linked with the Styx and

sprang from mineral springs (Strabo IV, 4, 5). Argil(l)a

probably corresponds to the Rumanian expression argea ‘hut’ and Albanian ragál ‘hut’

(Georgiev 1985: 5; 1977: 11). Geryon’s caves. According to

the Old Irish chronicle Lebar Gebàla, the earliest inhabitants

of Ireland were called fomoire. They lived in submarine crags and

caves on ragged cliffs towering like glass castles over the sea. The

description of their vertical rock-cut towers reminds us of Geryon’s

submarine caves mentioned by Greek myths. Geryon was another hero of

Iapethos’ progeny, he was Typhon’s son and Chimaira’s brother. He inhabited submarine crags

that were accessible only through the

entrances submerged in the water. In these caves Cimmerians deposed the bones of their

forefathers and their warriors met to practice chthonic cults with feasts on

human victims. Strabo gives a vivid description of the

subterranean caves called argillae used by the Cimbri at Cumae

in Italy. They were dug in rocks as vertical towers and at their bottom there

was a sacred well where visitors threw gold coins. Cave-dwellings were

characteristic also of the Kelteminar culture (4,000 BC) east of the Caspian

Sea. Their inhabitants were people of Turkic stock. Gebru. Near

Teheran and in Yezd and Kerman there is a group of cliff-dwellings in rocks

which may be attributed to the Gebru, a tribe of Zoroastrists, who preserved

this creed and habitation up to the 19th century. Zoroastrism was made an official religion by the Achaemenids,

who seized the rule in 522 BC. The Achaemenid rulers Dareios I, Dareios II,

Xerxes and Artaxerxes and constructed monumental rock tombs cut in the rock.

The Persian cave tombs have rich reliefs, columns and rock carvings. The

kings wear long hanging beards and Median tiara-shaped crowns. Similar

tombs were built by Russ I, King of Urartu. Phrygia, Urarte and Media were

three large centres of rock-cut funeral architecture. The origin of the

Achaemenid may be associated with the Tajik, Tat and Talysh.

V. V. Bartol’d (1925) linked the Tajiks with the Moslem tribe Tazi

of the 10th century AD and an earlier Arabic group Tai. They were

highlanders living in terrace houses (kishlaks) cut into steep rocks.

Their flat roofs were levelled with the ground and their inner rooms had numerous

niches. Their tombs were mostly cellars with niches and mounds (gūri

laxad). Ossuaries. The

architecture of artificial caverns in Palestine originated in the Neolithic

and its builders were the Jews and Phoenicians. The dead corpses in rock-cut

caves lay on elevated benches or in niches. Later they were placed in sacrophagi

out of stone, wood or clay (larnaces). Most corridors were sloping

down like shafts. The cave ossuaries with larnaces are usually

attributed to the Philistines, forefathers of Palestinians. The expansion of

burial caves to Punic Carthage was probably due to the Phoenician sailors. Scarab. The Phoenician rock-cut

graves contained sealing-sticks with the symbol of scarabs (Scarabaeus).

This beetle was a sign of the scarab god Cheprew and the sun god Amon

whose cult was introduced with rock-cut graves by the priests and pharaohs of

the Eighteenth Dynasty. Tutankhamen had several scarab amulets on his neck.

Amenhotep III edited memorial scarab gems on jubilee occasions. Large gems

contained a text from the 30th chapter of the Book of the Dead. They were

called ‘heart scarabs’ since they had to replace the heart after a mummy was

embalmed and deprived of bowels. The stone graves were cut into the limestone rocks in the

Valley of the Kings (Bībān el-mulūk) in the Upper

Egypt. This necropolis was founded by Amenhotep I, the first of Weset

kings. The military power of this dynasty rested on the title of kings of

Nubia. This dynasty kept regular marriage contacts with the Mitanni

and exhibited a Persian influence in the decorative entrances and columns in

front of the tombs. The tomb of Ramesses II is decorated by four statues of

the king depicting him with a high tiara or fez which was formerly typical of the Mitanni.

Table 1. Dwellings and burials in rock-cut

caves

Capsians. The Capsian

culture in North Africa (-8000) belonged to nomads who practised

mummification and used ostrich eggshells as vessels. Capsian caves exhibited

many rock drawings and cave paintings. The Guanches in Teneriffe prepared

real mummies and deposited them in large caverns. These caverns served as

ossuaries but also as shelters before enemies. The mummies were not wrapped

but stood naked as columns along corridors and galleries. A large centre of

artificial caverns is found in the Seine-Oise-Marne region. These caves cut

into a meek limestone composed of narrow entrances, sloping passages and

large ante-chambers. At the estuary of the Tago in Portugal they were cut

into cliffs. Within the range of the Greek world they were discovered in

Cyprus (-3000 to -2400), on the Cycladic Islands, in Attica, Euboia and on

Crete. R. Whitehouse’ paper The rock-cut tombs of the Central

Mediterranean proved their structural analogies with chamber-graves in

Britain (D. and R. Whitehouse 1975:

94). (Extract from

Pavel Bělíček: Prehistoric Dialects

II. Prague 2004, p. 546-549) |

Architectural

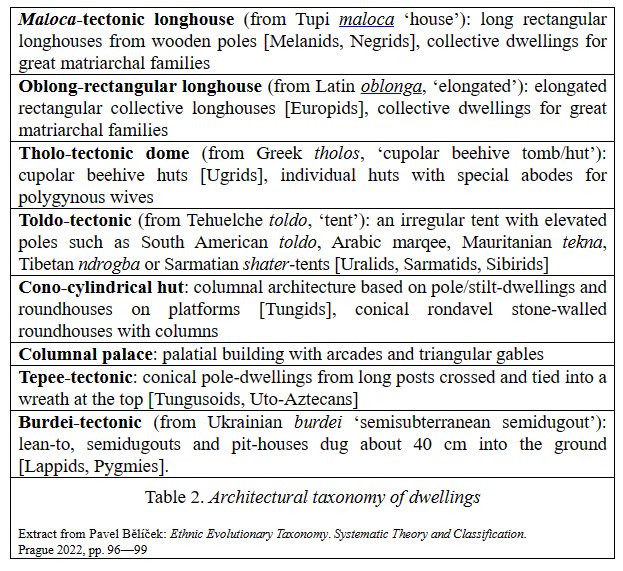

Taxonomy An alternative model of architectonic

classification may be submitted to consideration in Table 2. Its disadvantage

is seen in too many neologisms, great complexity and divergence from standard

conventions. Its specific trait consists in applying local terms as

archetypes for entire classes of similar buildings. If it displays a positive

feature worth pursuing, it is a series of compound words ending in -tectonic.

It indicates that the actual reference cocerns the systematic typology of

constructions in popular huts and folk architecture. They show that folk

architecture builds a bridge over the wide abyss between Palaeolithic and

Eneolithic morphology and disclose their structural continuity from times

immemorial.

|

|||

2 H. A. Bernartzik: Die

neue grosse Völkerkunde. Wien – Prag 1962.