|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

The Ancient Indigenous Architecture of Oriental

Farmers Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

|

||||||||

|

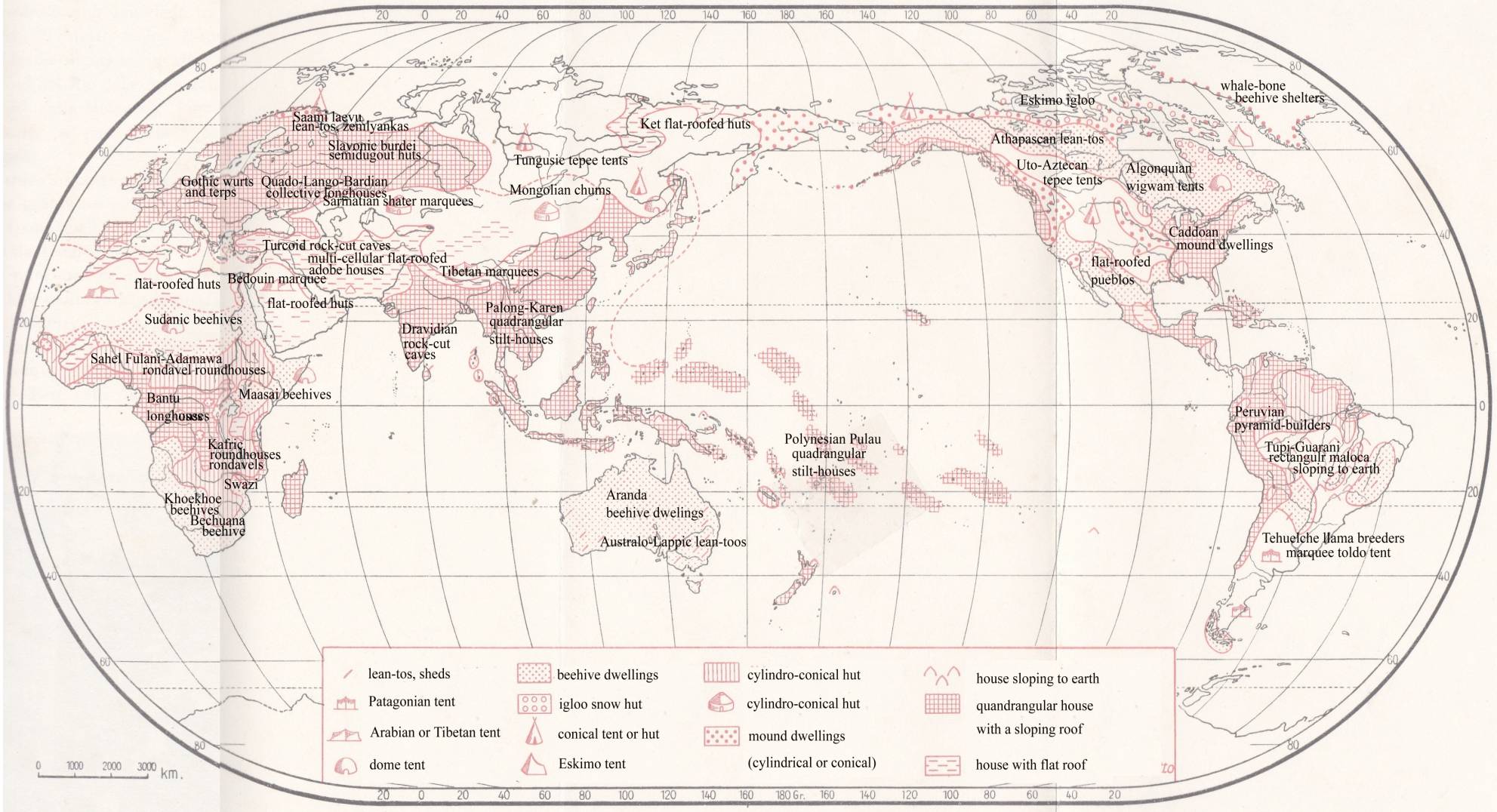

Map 1. Types of human dwellings (after R.

Biasutti) |

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

GENERAL ARCHITECTONICS

·

Evolution of human dwellings · Lakeside Stilt-Dwelling with Crossed Poles |

FOLK ARCHITECTURE § Cliff-Dwellings and Burial Rock-Cut Caves

§ Rectangular

Longhouses Out of Straw and Mud

§

Earth

lodges and Subterranean Sancturaries § Semidugout Zemlyankas of Lapponoid Cremators

|

TYPES OF DWELLINGS

§

Tungusoid teepes,

pile-huts and lake-dwellings

§ Pelasgoid conical rondavel roundhouses§

Megara, palatial

temples and columnal palaces

§

Flat-roofed

labyrinth architecture of Oriental farmers

§

Rectangular wicker longhouses with

thatched roofs

§

Gotho-Frisian

wurts, terps and half-timber longhouses

§

Dome-shaped beehive huts

§

Irregular

multi-peaked marquee nomadic tents

·

Epi-Aurignacian

tepees and pile-dwellings

·

Bascoid Cyclopean megalithic

architecture

·

Megalithic

tombstones and tholoi graves

·

Lapponoids’ lean-to and semidugout pit-house

·

Turcoid dwellings

and burials in rockcut caves

|

ANCIENT SETTLEMENTS §

Lakeland,

marshland, lowland, grassland and desert ecosystems §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites

in oases of subtropical shrublands §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites in

oases of subtropical shrublands §

Oppidans:

hillforts towering on high rock promontories §

Getic boroughs:

villages in alluvial lowlands §

Palatial poleis

and cultic spas in seaside harbours §

Straight streets

and alleys of lake-dwellings |

|

||

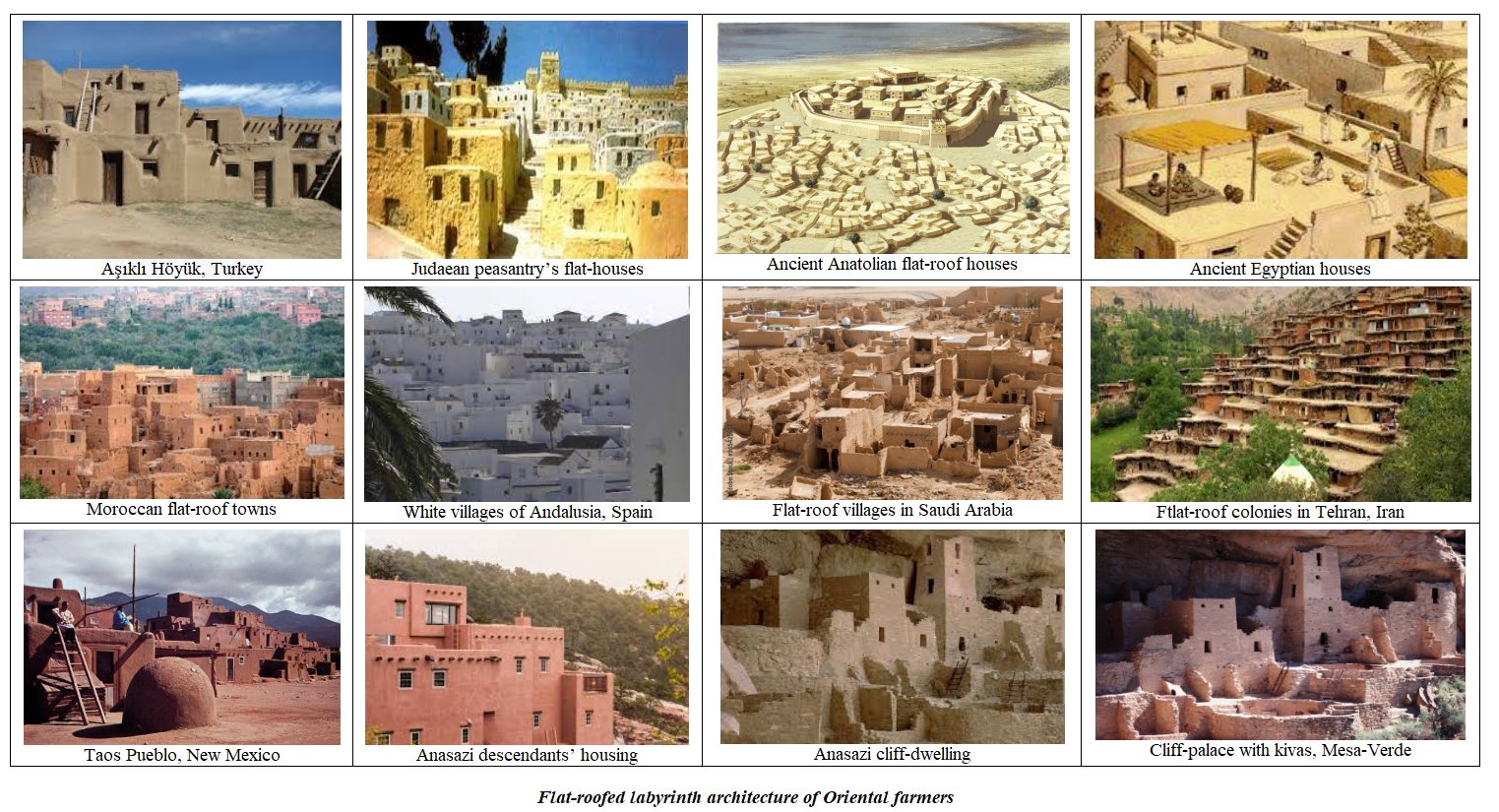

Tell-Site, Multi-Cellular Flat-Roofed

Labyrinth, Pueblo

Tell-sites. As

the Neolithic peasants applied shifting agriculture, they regularly abandoned

their settlements and returned to them in periodic cycles. When leaving old

homes, they set their houses on fire and furnished the village as a necropolis

of their dead ancestors. After returning, old ruins were pulled down and new

walls were erected on their remains. Every generation of inhabitants elevated

the mound by adding a new storey and so the tell grew high like a

mushroom. Tell Brak in Turkey was 40 metres high, Tepe Gaura in Iran 20 m

high and the Karanovo tell in Bulgaria 12 m high. Most tells in

the Tisza basin were hardly more than 3 metres in height. High tells

were common in Turkmenistan (Anau culture, Namazga Tepe), in Palestine

(Jericho I, -7,800), Assyria (Tell Hassuna), in Caucasus (Tepe Hissar) and

southeast Europe (Karanovo I). The Linear Ware people in Central Europe built

only lower mounds, because free land gave more space for migrations. The

Frisian wurts on sand-dunes seem to be their trueborn heirs in the

outer layout and design. The Arabic word tell

meant a ‘heap, mound’ while the Iranian tepe denoted a ‘hill’. In

Turkmenistan their equivalent was depe, in Egypt such settlements were

referred to as kom. In Turkey several tells are denoted as hüyük

‘hillock’. Common people usually assumed that mounds were tombs for the dead.

This etymology is clear in the Macedonian term magula and the word tumba

in Thessaly. The Mound Culture in North America illustrate a tendency of some

peasants’ settlements to turn into a necropolis and a large tomb for

the dead. Tells resulted from needs of

itinerant agriculture. Mesopotamian peasant communities huddled in large

urban units reminiscent of multi-roomed labyrinths because small villages were

assailable by nomads. Their settlements had usually windowless walls

enclosing a honeycomb of small family rooms around the central atrium

courtyard. The small rectangular rooms had walls made of compact clay or

cells separated by hanging reed mats. Younger generations were expected to

annex their premises to their parents’ homes at adjacent ends. The flat roofs

allowed younger families to add their own annexes on the roof of their

parents’ flat. In front of the central atrium we could was a temple or men’s

communal room for administering ancestral cults. Pisé. In Mesopotamia wickers with mortar out

of clay and mud were often replaced by adobes, sun-dried bricks of convex

shape. The mortar was usually thickened by straw, hay, chaff, leaves, shreds

or stones. Sometimes the half-timberwork was filled by this material to form

a maison en pisé out of rammed clay and gravel. In a rainy weather the

adobes got soaked and the hut was prone to destruction. The short-time

durability of pisé houses explains why new huts had to be built soon

on the ruins of older buildings. Another reason of frequent destructions of tells

was the need of shifting agriculture to move to new fields. Moving to new

homes was ritualised by ‘hut burials’: if the eldest grandmother died, her

grandsons set the whole tell on fire as a necropolis for the

dead ancestors and moved to a new place.

Longhouse. In Mesopotamia

most tells are fortified strongholds with cell-like multi-roomed

units. The well-known Linear Ware settlement in Köln-Lindenthal suggests that

the original form was a ‘longhouse’, a large communal dwelling whose size

could reach 36 metres in length and 10 metres in width. It was inhabited by

great matriarchal families and its inner space could be divided by mats into

smaller rooms with individual ovens. The wooden construction stood on central

pillars (with the frontal pole as a totem) and often also on the roof

slanting down to the earth. The sidewalls from timber and wickers formed

three aisles. If the roof was slanting down to the ground it could shelter

side naves usable for the cattle. The mortar was from straw, chaff and mud.

Similar principles of building constructions were envisaged in Frisian wurts

and Saxon half-timber houses. Kiva. The

roof could have gables that were of a saddle shape and often resembled

upturned boats. They were decorated with boukrania (bull-skulls)

symbolising cultic totem animals. The flat roof was designed as a balcony for

women, who cooked meals and took care for their children. In order to fend

off attacks from without, the house had not doors and windows, the only

access for entering its interior was provided by removable ladders. The

underground space was occupied by a central hall called kiva in Mexican pueblos.

It served as a central meeting hall and a sanctuary for gatherings. The

outstanding thatched roof could form an anteroom with two frontal pillars and

evolve into the classical megaron house. The Greek megaron

was not a large communal house but its hybrid application to a palace.The megara

are known from Sesklo, Dimini and Hacilar where they consisted from the

entrance-hall prodromos and the inner room called telamos. In

the rear behind the oven there were often large jars and amphorae dug

with their bottom into the ground floor. At the earlier stages their function

was fulfilled by deep lined storage pits in the floor, coiled baskets and

granaries. Pits in the floor could also make up for furniture, beds and

benches could be formed by elevated platforms from mud and clay. There were

infinitely many variations but two principles remained constant: the houses

were of oblong, quadrangular shape and the overhanging roof tended to form

side naves and anteroom spaces. Megara seem to have close parallels in

Mingrelian houses in Georgia. Their smaller size, frontal columns and

placement on fort-hills, however, suggest heterogeneous influences. Pagoda. The Neolithic excavations from China bring

evidence for both subterraneans and light quadrangular houses. The latter

type in East Asia probably developed into a pagoda with concave roofs.

The Melanesian and Polynesian convex roofs slanting down to the earth led to

boat-houses and aisle dwellings with naves. The dwellings with side

naves were very common in Melanesia, in Brasil and in Scandinavia. The long

houses out of wooden planks were popular among the Iroquois and Nootka tribes

in America. The gables bore totem emblems.

Subterraneans. The Neolithic

settlements of the Amur and Osinovki culture were excavated at Kondon,

Souchou in Kamchatka and in Sakhalin. The habitations of these tribes were

large subterraneans huddled like mounds with many inner cells that could be

accessed by large chimney entrances on logs with notches serving for ladders.

A village on the islet of Souchou in the Amur region is 4 metres deep and its

circumference is about 90 metres. The inner woodwork consisted of several

concentric circles of pillars. New families were allowed to append their own

cell and this way the whole village grew wider. The women, children and the

cattle were allowed to use a horizontal entrance leading to the riverbank.

Under the chimney hole there was a rectangular hearth, a pit with sides 1.9

metres wide. |

Cliff-dwellings. he Anasazi Basket-Makers (120 to 500 AD)

were peasants growing maize, beans, tobacco and gourds. They lived in large

centres built under overhanging rocks. Their abodes were semidugouts and

subterraneans reminiscent of cliff-dwellings and artificial caves dug out in

the sandstone rock overhangs. The single cells led to the central shaft which

joined different storeys. The inhabitants could climb up the ladders to the

chimney-hole entrance or descend to lower storeys where the men met in their

clubroom kiva. The bottom of the pit was a well, a cult tsenot

where the inhabitants threw away golden rings and other offerings. Such

characteristics confirm our suspicion that the subterraneans and labyrinth

houses had been corrupted by elements due to the Turkic cave-dwellers and

cliff-dwellers. Pueblos. After

500 AD the Anasazi people probably transformed into the Pueblans. The current

dating is 700-900 AD for Pueblo I, 900-1050 for Pueblo II, 1050-1300 for

Pueblo III and 1300-1700 for Pueblo IV. The pueblo dwellings were

large communal settlements made out of sun-dried bricks. Pueblos were

multi-roomed habitations looking like fortified castles. The walls had no

outer apertures and doors, they were accessible only by ladders. The roofs

were flat and full of ‘doors’ or holes which led down to a small courtyard (atrium).

One group of maize-cultivators lived in the Californian earth lodges, which

were simple semidugouts with inner timberwork covered with a thick layer of

earth. The

Pueblo Bonito in Gran Chaco (12th century AD) represented a large

settlement under a canyon overhang which concentrated 600 rooms in a closed

half-circle with several concentric rows. Central rooms were open from above

and served as staircases with ladders. They had no windows or doors and

served for communal meetings at the hearth of the great family. Another

centre of social life was the roof. Individual members lived in side cells

with no hearths. The inner yard had a subterranean kiva for men.

Table

1. Earth lodges, publo dwellings, cellular

labyrinths Casas grandes. The Pueblans spoke Uto-Aztecan languages, only the

Keres belonged to the Siouan-Iroquois family. The Sioux were composed of the

buffalo-hunters Dakota who dwelt in skin tepees, and the eastern

corn-cultivators who lived in earth lodges. Large pueblo dwellings may

be compared to casas grandes in Arizona, the open-air settlements of

the pisé type, built of huge blocks of adobe mortar and gravel. One of them

was Casa Montezuma, the great Indian chief’s last abode (Hodge 1907: I, 211;

II, 578). The Chalco culture of

Mexico seems to be a probable ancestor of the Maya and Quiché. From 3,000 BC

we may detect a continuous seed-gathering culture, from 1,000 BC we may speak

of a regular peasant economy. Some settlements recall the Casas grandes.

There was a marked tendency to build large urban communities such as Chichen

Itza, Uxmal, Palenque, Piedras Negras. Most of them had staircase walls that

could be climbed. The pyramid structure resulted in an acropolis with

a temple, long houses and a cult well

(tzenot) for ritual offerings. The highest priest, halach

winik, had his teeth mutilated by grinding them in V-form. His earlobes

were perforated and hung with turkeys’ eggshells. The Tupí-Guaraní villages

consist of three or more quadrangular huts (maloca) sheltered by

saddle-roofed structures. Such huts encompass the central place with a

circular ground-plan, dominated by a communal house. The whole community may

be inhabited by 70 or more people, the single huts being occupied by grand

families governed by elderly women. Most peasants in the Amazon basin live in

high ‘long houses’ with overhanging roofs. Some roofs slant down to

the earth and resemble upturned boats (Holmes 1919: 141ff., Steward 1946-:

III, 117). (Extract from

Pavel Bělíček: Prehistoric Dialects

I. Prague 2004, p. 193-197) |

|

||||