|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

The Ancient Indigenous Architecture of Lapponoid

Tribes Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

|

||||||||

|

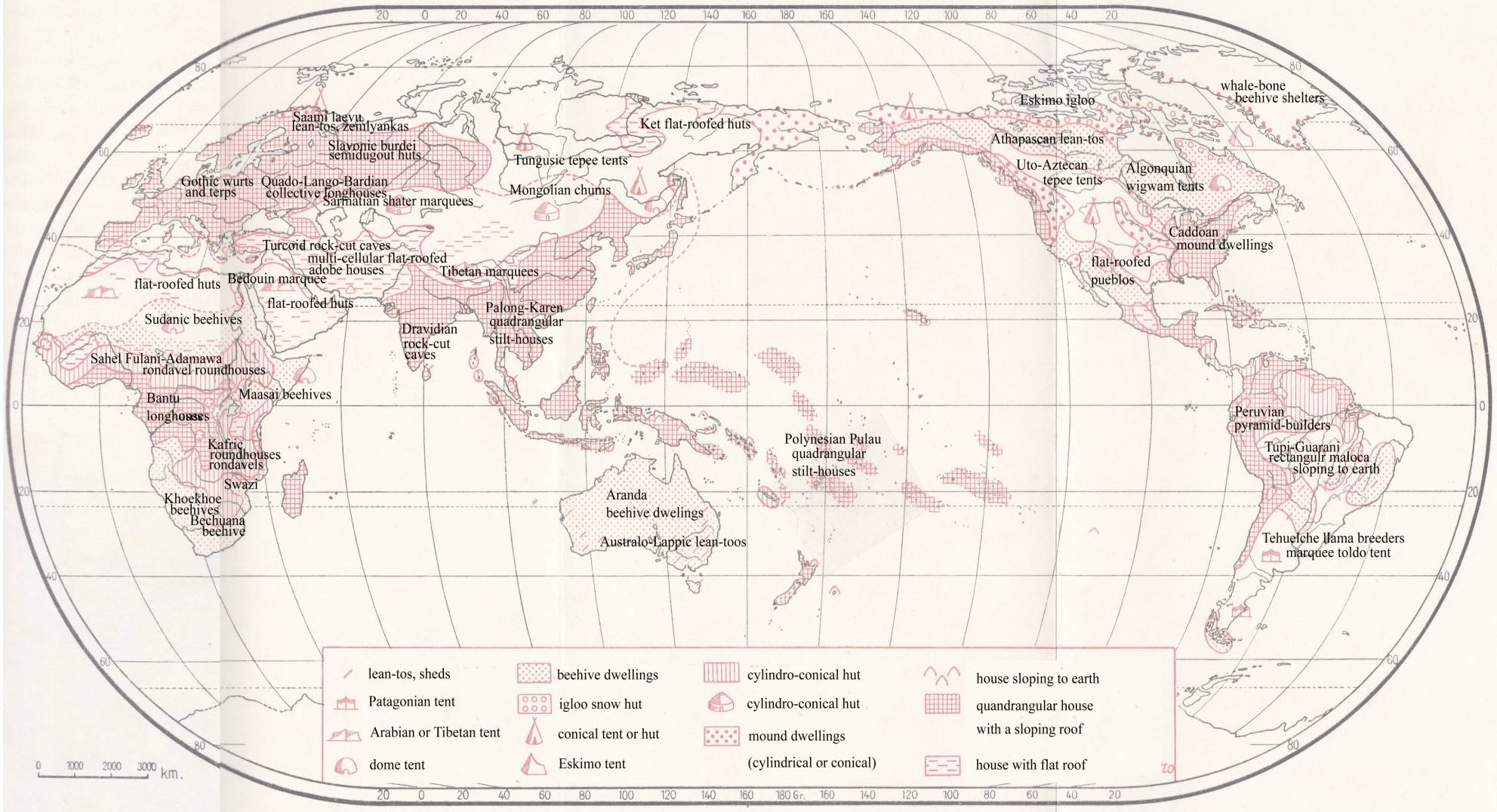

Map 1. Types of human dwellings (after R.

Biasutti) |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

GENERAL ARCHITECTONICS

§

Evolution of human dwellings § Lakeside Stilt-Dwelling with Crossed Poles |

FOLK ARCHITECTURE § Cliff-Dwellings and Burial Rock-Cut Caves

§ Rectangular

Longhouses Out of Straw and Mud

§

Earth

lodges and Subterranean Sancturaries § Semidugout Zemlyankas of Lapponoid Cremators

|

TYPES OF DWELLINGS

§

Tungusoid teepes,

pile-huts and lake-dwellings

§ Pelasgoid conical rondavel roundhouses§

Megara, palatial

temples and columnal palaces

§

Flat-roofed

labyrinth architecture of Oriental farmers

§

Rectangular wicker longhouses with

thatched roofs

§

Gotho-Frisian

wurts, terps and half-timber longhouses

§

Dome-shaped beehive huts

§

Irregular

multi-peaked marquee nomadic tents

·

Epi-Aurignacian

tepees and pile-dwellings

·

Bascoid Cyclopean megalithic

architecture

·

Megalithic

tombstones and tholoi graves

·

Lapponoids’ lean-to and semidugout pit-house

·

Turcoid dwellings

and burials in rockcut caves

|

ANCIENT SETTLEMENTS §

Lakeland,

marshland, lowland, grassland and desert ecosystems §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites

in oases of subtropical shrublands §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites in

oases of subtropical shrublands §

Oppidans:

hillforts towering on high rock promontories §

Getic boroughs:

villages in alluvial lowlands §

Palatial poleis

and cultic spas in seaside harbours §

Straight streets

and alleys of lake-dwellings |

|||

The Subterranean

Habitations of Cremating Tribes

The Pygmids are called

‘forest people’ because they avoid civilised life. They avoid large villages,

roads and paths and living aloof in the rain forest scattered in small

groups. They lead a nomadic life, wandering in large circles and staying

overnight in temporary camps. They move in small hordes not exceeding twenty

members of a small clan. They live in small monogamous families, usually from

three to five marital couples surrounded with throngs of little children.

Their housing developed in several stages: (1) wind-screen, (2) double

lean-to, (3) semidugout hut, (4)

sweat-house sauna. If we want to trace their evolution, it is more convenient

to enquire into their architecture in an ascending order from Tasmanian

isolates to Lappish sweat-house saunas.

Windscreen. A single windscreen

was used as a protection against cold winds for camping overnight in

Australia and Tasmania. It was formed by one leant sloping platform of boughs

with leaves that was supported by one or two posts on the upwind side. The

Athapascan Indians used a simple windscreen only for summertime camps. The

Yokuts had a summer windscreen called ramada from poles and boughs.

The Chukchanai had similar brush houses of boughs. These shelters were

accompanied by ‘earth baths’ functioning as the earliest earth-dwellings.

Whenever the Sanids wanted to protect their body from heat or cold in high or

low temperatures they buried their body in sand up to their necks. This

method enabled them to survive scorchers as well as frosts.

Double lean-to. Up to recent times most Sanids and

Pygmies in Africa used a double lean-to tent, a provisory dwelling consisting

of two wooden platforms leant against one another and supported by one

central post (Bernatzik 1962: 188, fig, 53). The inner gables remained empty

without any sidewalls. The platforms were made of boughs covered with large

banana leaves. The tent was sunk into the earth in case of severe weather or

a longer stay. One of standard Athapascan habitations was a double lean-to

consisting of two thatched sides enclosed by a gable from each side (Driver

1973: 118ff.). A different type was used by

Epi-Gravettian colonists who drifted from Spain and Sicily to eastern

Europe. Their dwelling at Dolní Věstonice

in Moravia (Jelínek 1972: 232) looked like a standing locust whose long

wing-sheaths sloped down to the earth and were supported by posts serving as

the front entrance. In the Ukraine the dwellings reconstructed at a site in

Kostienki I look like subterranean lodges of pear-like shape. Such a

subterranean semidugout became later known as a zemlyanka and remained

a common type of architecture up to the Slavonic period.

Pyramids. The typical house

of Athapascans was a shallow pit lodge consisting of a four-pitched pyramid

made of logs supported by a rectangular framework of horizontal logs. It was

occupied by at least three families, each possessing a wooden log side

platform used as a bed. The southern Athapascans applied hemispherical shapes

and conical huts of bark but these types should be omitted from consideration

as secondary loans. Such conical pyramids, sunk half a metre into the ground,

enjoyed wide popularity also among the Lapps and Samoyeds. Their

architectonical style would class them as Athapascan relatives without

Epi-Gravettian roots.

Semi-dugouts. The Yokuts preferred to build houses

that were round or oval in their ground-plan, and sank their floor two feet

below the ground level. The floor was stamped hard by feet and had special

wooden platforms by the side that served as beds. The Monache and Coastal

Miwok had houses with excavated floors. In their middle there was a central

depression for a hearth dug up one more foot deeper (Sturtevant 1978: VIII,

430). The Maidu made deeper earth lodges and subterranean assembly halls,

some being four feet in depth. The centres of larger communities were

occupied by larger assembly subterraneans, which were deeper and covered with

earth. The Nisenan called it k’úm, a dance house. It was three or four

feet deep and it had three or four poles. Other tribes of cremating

incinerators in Californian would do with just one foot as the average depth.

At the top of the construction there was an exit for smoke. The roofs from

bark flanks were supported by the rectangular inner construction of logs

holding the corners. The outer edge of the hut was often banked by a ditch or

a mound so that no water might soak in. |

Sweat-houses. The winter earth-covered semi-subterranean lodges were air-tight and

too hot for summer housing. Athapascans combined them with summertime

windscreens and wintertime sweat-houses. The sweathouses for men had similar

constructions. Besides, there were granaries for acorns and menstruation huts

for young girls (Kroeber 1925: 407ff.). The Athapascan sweat-houses as well

as their primitive varieties among Californian tribes must have had a common

origin with the saunas of the Finnish Lapps. We explain them as a natural

product of ‘pyrolithic’ heating and boiling techniques. This consisted in

glowing stones and throwing them in a red-hot state into the snow or a tub

with water. The vapours could heat the subterranean lodge without keeping the

hearth burning all night. The cremating tribes of

California never gathered into large village communities. The Maidu

constructed their dwellings on elevated places in a mixed coniferous forest.

Their settlements lay on low hills, ridges or edges of valleys. Every valley

defined a closed village territory. The huts were scattered unevenly in small

hamlets. The Maidu houses were inhabited by five persons on average and their

villages consisted of seven houses surrounding the central earth lodge used

as an assembly hall. The total population of a village amounted to 35 people.

Three or five villages were loosely joined into a village community of about

200 people united under one headman or chieftain (Kroeber 1925: 397). The

Monache were scattered even in smaller units. Having no central villages and

communities, they were dispersed in small hamlets. They ranged from one to

eight huts with an average of three huts. Most included thirteen 13 people

per place (Sturtevant 1978: VIII, 431). In South America the Arawak

tribes lived in larger houses but had preserved scattered patterns of

habitation to a great extent. The Betoi did not dwell in large villages

communities but built their huts in small hamlets called caseríos or rancheríos.

Their typical abode, called caney, could house an extended family

under a loose construction of poles. Its roof was usually thatched with grass

(Steward 1948: IV, 394). Young married couples often chose to build a house

of their own in a secluded place in the forests. They did not like joining

their family and old folks in the hamlet. They also avoided a close

neighbourhood of the bridegroom’s parents. (Extract from

Pavel Bělíček: Prehistoric Dialects

II. Prague

2004, p. 646-648) |

|

||||