|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

The Ancient Indigenous Architecture of European Farmers Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

|

||||||||

|

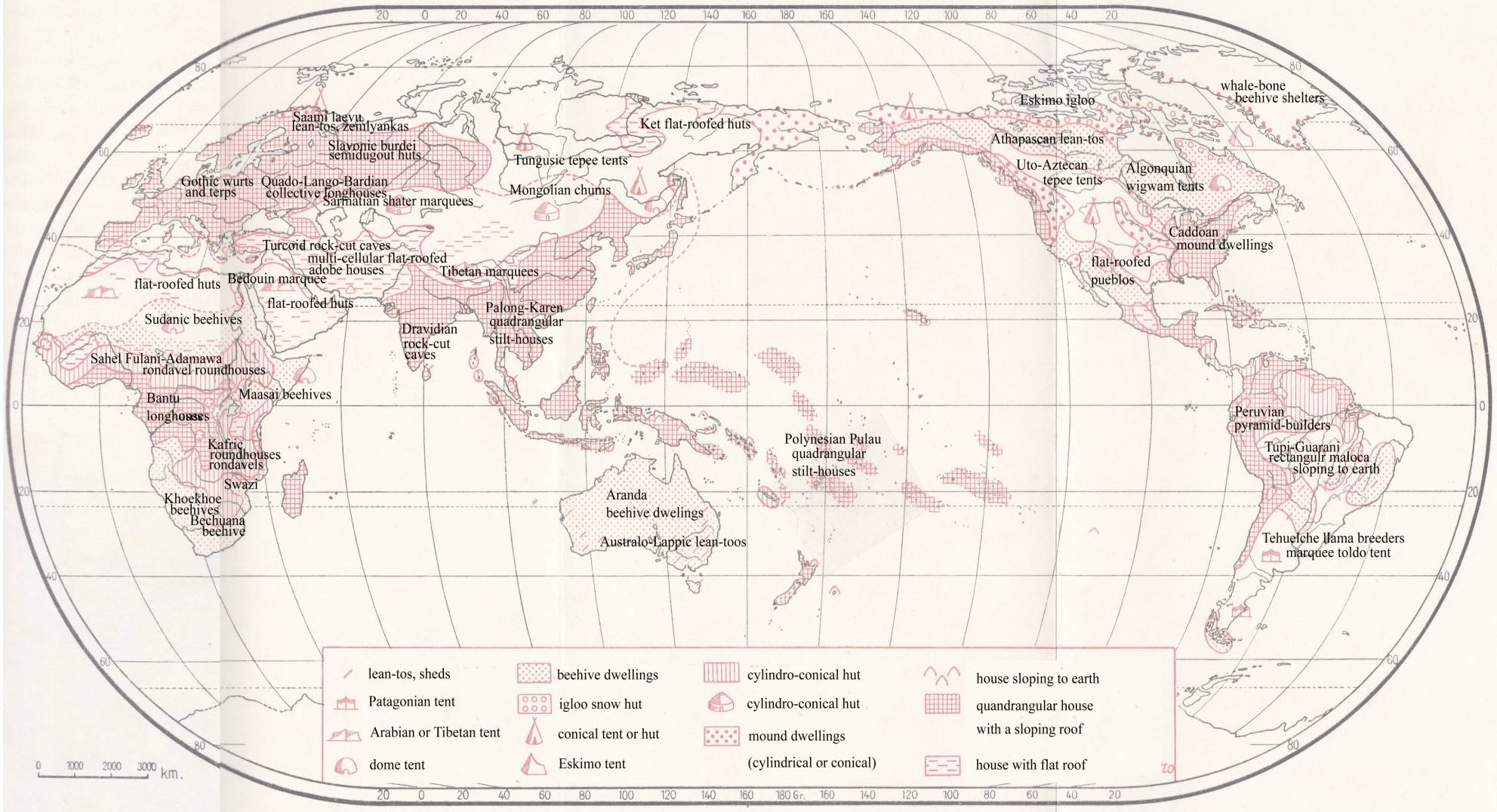

Map 1. Types of human dwellings (after R.

Biasutti) |

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

GENERAL ARCHITECTONICS

|

FOLK ARCHITECTURE § Cliff-Dwellings and Burial Rock-Cut Caves

§ Rectangular

Longhouses Out of Straw and Mud

§

Earth

lodges and Subterranean Sancturaries § Semidugout Zemlyankas of Lapponoid Cremators

|

TYPES OF DWELLINGS

§

Tungusoid teepes,

pile-huts and lake-dwellings

§

Pelasgoid conical rondavel roundhouses

§

Megara, palatial temples

and columnal palaces

§

Flat-roofed

labyrinth architecture of Oriental farmers

§

Rectangular wicker longhouses with

thatched roofs

§

Gotho-Frisian

wurts, terps and half-timber longhouses

§

Dome-shaped beehive huts

§

Irregular

multi-peaked marquee nomadic tents

·

Epi-Aurignacian

tepees and pile-dwellings

·

Bascoid Cyclopean megalithic

architecture

·

Megalithic

tombstones and tholoi graves

·

Lapponoids’ lean-to and semidugout pit-house

·

Turcoid

dwellings and burials in rockcut caves

|

ANCIENT SETTLEMENTS §

Lakeland,

marshland, lowland, grassland and desert ecosystems §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites

in oases of subtropical shrublands §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites in

oases of subtropical shrublands §

Oppidans:

hillforts towering on high rock promontories §

Getic boroughs:

villages in alluvial lowlands §

Palatial poleis

and cultic spas in seaside harbours §

Straight streets and

alleys of lake-dwellings |

|

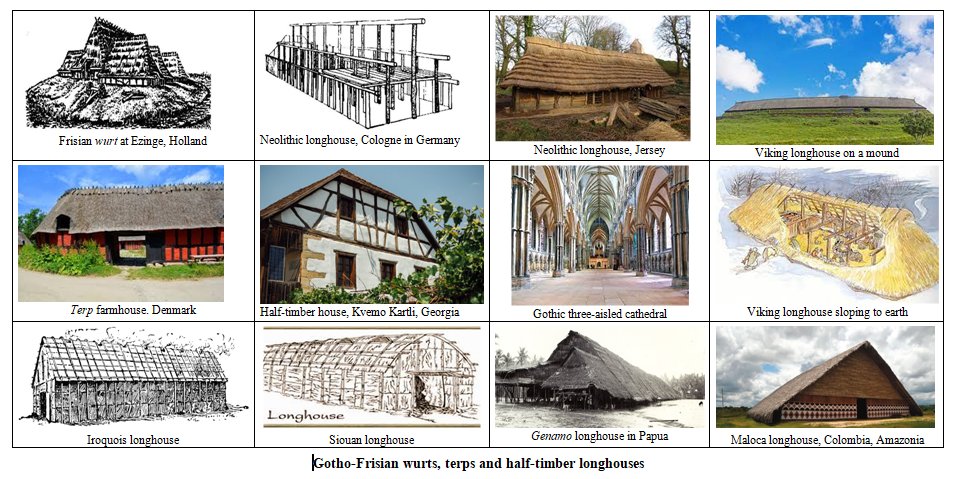

Rectangular Longhouses Out of Straw

and Mud

It is fascinating to find

that most folk customs in European ethnography can be safely derived from

Caucasoid and Palaeo-Negroid roots: parents’ marriage contract, dowry,

matrilinear affiliation, hand-axe traditions, agriculture, ancestral and

chthonic cults, ascetism, mysteries as well as folk festivals. A consistent

link in this typological network is represented also by architecture. We may find

a conspicuous structural isomorphism between the modern Saxon half-timber

architecture, Frisian wurts, Gothic cathedrals, Neolithic ‘long

houses’, Bantu clay houses and Melanesian quadrangular huts. The long

quadrangular house ought to be considered as a definite typological unit

standing in clear opposition to the Hamitoid round beehive huts (tholoi),

Turcoid tall conic post-dwellings (tepees) and the

Lapponoids’ semidugouts (zemlyankas). The round roofs in Africa

are of Mousterian origin, the conic pointed roofs of Levalloisian descent and

the oblong rectangular structures of Sangoan or Acheulian provenience. The common features of the

Palaeo-Negroid long-house architecture include: (a) settlements on

dunes, mounds, tells, kitchen middens and other small elevations, (b) large

long houses of quadrangular form, (c) wooden timberwork, (d) tall roofs

sloping down to the ground, (e) walls from wicker osiers, (f) wickered walls

fixed with mud, later with sun-dried clay bricks, (g) mortar made from cut straw

and mud, (h) floor from trodden clay, (i) thatched roofs, (j) the galleries

along the walls and upper stories used as

bedrooms, (k) clay ovens in the centre, (l) opening in the roof for

smoke used as impluvium, (m) rows of pillars dividing the inner room

into three or five aisles, (n) side rooms under the roof used as stables for

cattle and domestic animals, (o) saddle roofs with decorative gables, (p) boukrania

and totem symbols on the gables, (q) main entrances under the front gable,

(r) sheltered columns forming outdoor verandas, (s) head-benches and tripods used as furniture, (t) no cellars and

ceilings, space under the roof used for drying onions and other vegetables,

(u) descendants’ huts adjoining their parents’ central hut in radial circles,

(v) quadrangular palisades and fences around huts and the village, (w)

backyards for family clans, (x) men’s and women’s huts for ritual meetings. Apart from these common

traits the Neolithic peasants’ straw-and-mud architecture displays also

several variant styles. One tradition applies long terrace houses with saddle

roofs, verandas and pottery with spiral patterns and tripods. This seems to

be predominant in Greece, the Danube basin, Central Africa, China and

Melanesia. A different style was devised by peasants in Egypt, Mesopotamia,

Elam, Turkmenistan and Harappa. Their civilisations preferred labyrinth

houses with many cellular rooms. Usually one quarter of a town was formed by

a many-room labyrinth concentrated around one central yard. Such quarters were

inhabited by one large family, guild or clan, their outer walls were without

any windows and neighboured on other blocks of flats, separated only by

narrow lanes. The inner windows led to a central atrium or impluvium,

the access was through a ladder from above. Originally such houses were

subterraneans accessible through chimney-holes and ladders from above. These

atrium houses had usually flat roofs and walls of square shape, there were no

verandas, only columns inside the rooms. The typical ornament was a chequered

matting style. It is of interest that Amerindian farmers of the Hopi and Zun)i extraction built their casas grandes in the

Mesopotamian style and applied also the chequered ornament while the Tupí and

Guaraní clung to the older saddle-roof tradition. Labyrinth houses may be

interpreted as a Neolithic outgrowth of Mesopotamian cultures with b-languages.

We suspect that they represent a compromise of the Australo-Negroid

quadrangular hut with Asiatic subterranean cave-dwellings. The peasants’ farming

originated from shifting or fallow agriculture. Neolithic tribes living on

corn and fruit prepared their fields by burning forests. The soil soon got

exhausted and after three or five years they had to move to new areas.

Harvesting festivals or games gave opportunity for initiating 5-year age

classes. Young boys and girls got married in collective wedding rites and the

whole clan went on a journey to find a new home. The dead were buried in the

old huts and the whole village was left as their necropolis or cemetery.

After twenty years the exhausted fallow land was able to grow corn again, the

ruined or burnt old village was reconstructed and grandsons built a new long

house on the old ruins. This explains why most Neolithic sites stood on high

mounds (often as much as eight metres high). These mounds were called tell

in Mesopotamia (Tell Hassuna, Tell Halaf) and tepe in Iran

(Namazga-tepe, Kara-tepe). The highest tell of the Danubians was in

Karanovo in Bulgaria, while the Neolithic ‘long houses’ and the Frisian wurts

stood only on seaside dunes. The typical Bantu house in

Congo is an oblong saddle-roof house with bamboo rafters and boughs

interwoven into walls. The small square entrance with a very high threshold

looks like a low window. These huts have usually outside and inside bamboo

pillars forming indoor galleries and outdoor verandas. The inner space is

divided into an anteroom and a bedroom. The roofs are usually formed by two

thatched sloping planes covered with straw or boughs of palms. Wicker walls

are typical of the Kundu, whose house usually stands on an earthwork mound

with ramparts. In the Bayanzi villages it was about 2 metres high. The old

Bantu often ate their meals in front of their huts and reserved them only for

sleeping at night (Frobenius 1933: 227). Patterns of the true Bantu

architecture are corrupted in South Africa by the Hottentot dome-shaped

beehive huts (pontok) and the Zulu conical houses. Farmers tend to

build quadrangular huts also in Nigeria, Ghana, Sudan, Morocco, Egypt and

oases in Sahara but these dwellings have usually flat roofs and clay walls.

The Hehe hut in Tanganyika, called tembe, has subterranean galleries

and labyrinths like that of the Mopti in western Sudan and the Figuig in

North Africa. We assume that these labyrinth houses may be a hybrid

compromise with the Turcoid cave-dwellings, which holds especially for the

subterranean dwellings of the Corded Ware cultures in northern Russia and

Siberia. The Diola in Senegal, Bamum and Bamileke in Cameron lived in blocks

of quadrangular huts whose roofs were sloping down to a central impluvium

with a small basin for rainwater.

The Neolithic farmers of Egypt, Palestine, Mesopotamia and Iran

applied reed matting fastened to

posts. The Ubaidans made use of closely tied bundles of reed plastered with

mud. Matting huts were common also among the Fayumis and Merimdians in Egypt.

Later the reed mats were replaced by pisé consisting of soil, mud or

clay tempered with chopped straw, reed and dung, mixed with water and well

rammed or trodden into a compacted stuff. In Syria and Anatolia people used

walls from wattle and daub. The Danubian ‘long houses’ were of split sapling

and wattle. Only later Mesopotamian peasants began to make sun-dried bricks

of plano-convex hog-backed shape. |

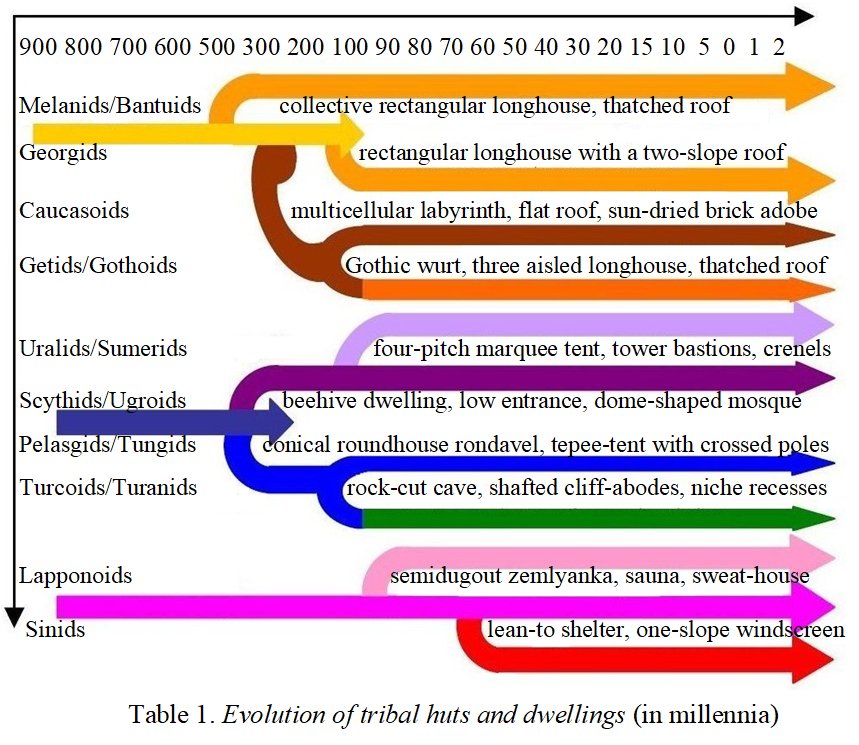

Table 1. Long rectangular wicker houses with thatched roofs The Neolithic houses huddled

into irregular multi-roomed labyrinth structures with several courtyard

centres and small impluvia for each clan and family. One large clan

inhabited a quarter of a town fortified by high windowless walls. Quarters

separated by narrow lanes could be approached through a gate leading to a

courtyard for foreigners. Usually one central parental house grew into a

cobweb of adjacent smaller outbuildings and daughter houses filling the space

between neighbouring huts. Neolithic peasants in China

made use of pit-dwellings with walls from interwoven wicker network plastered

with mud. They were covered by reed-matting roofs and approached through a

ladder from above. Later they were replaced by oblong huts on terraces from

trodden mud. The inner room was divided into an anteroom and a bedroom with a

khang, a large bed of compacted soil heated with an oven. The Melanesian villages are

clearings in tropical forests which have a quadrangular form and a round

communal house in the middle. The ordinary huts rim the sides of the forest

clearing with their quadrangular walls and high roofs slanting down to the

ground, being often concealed under the trees. They are usually formed by

high roofs supported by several rows of tall posts. (Extract from Pavel Bělíček: Prehistoric Dialects I. Prague 2004,

p. 144-149) |

|||