|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

The Ancient Indigenous Architecture of Lakeland Fishermen Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

|

||||||||

|

|

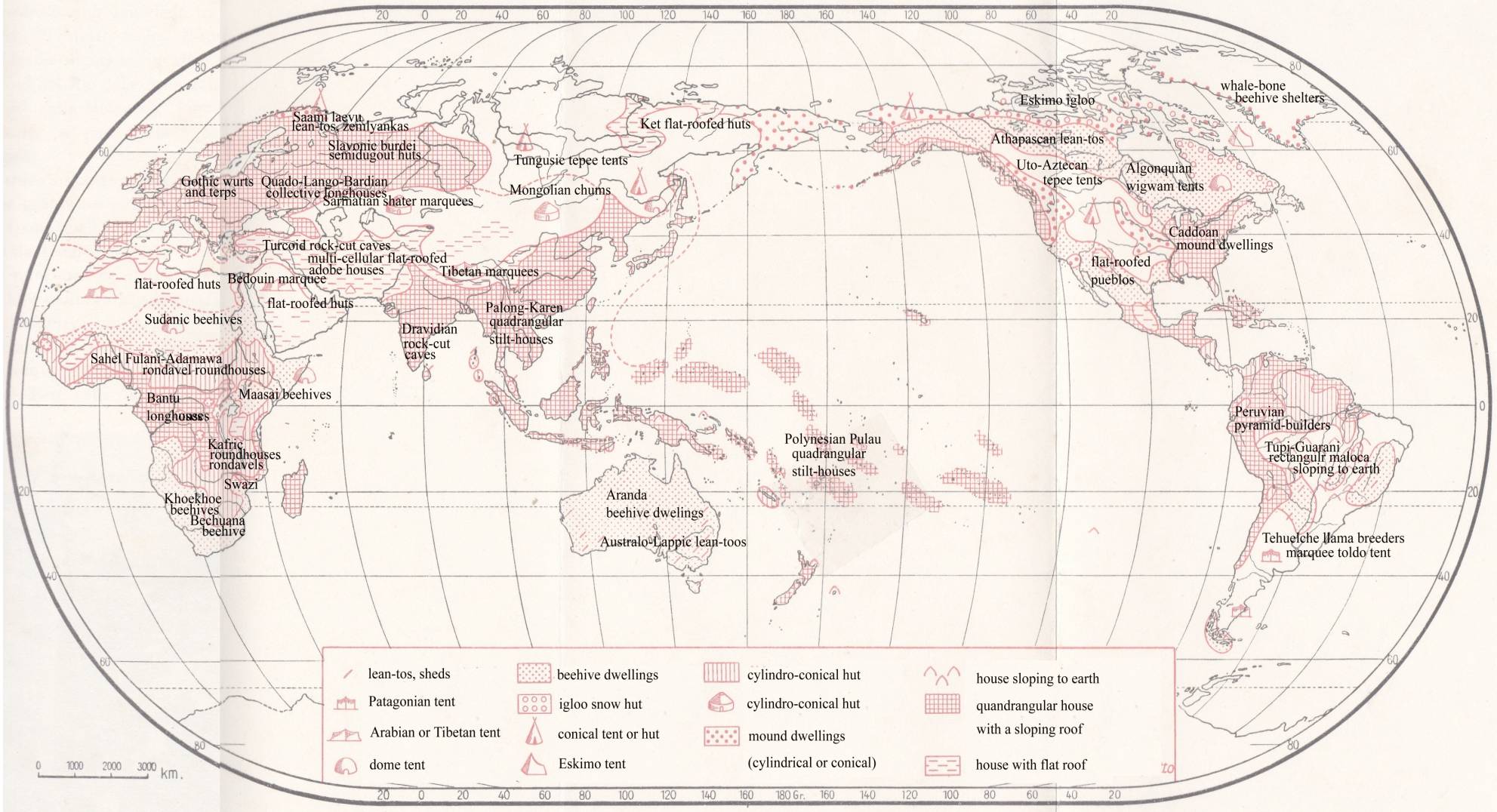

Map 1. Types of human dwellings (after R.

Biasutti) |

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

GENERAL ARCHITECTONICS

|

FOLK ARCHITECTURE § Cliff-Dwellings and Burial Rock-Cut Caves

§ Rectangular

Longhouses Out of Straw and Mud

§

Earth

lodges and Subterranean Sancturaries § Semidugout Zemlyankas of Lapponoid Cremators

|

TYPES OF DWELLINGS

§

Tungusoid teepes,

pile-huts and lake-dwellings

§ Pelasgoid conical rondavel roundhouses§

Megara, palatial

temples and columnal palaces

§

Flat-roofed

labyrinth architecture of Oriental farmers

§

Rectangular wicker longhouses with

thatched roofs

§

Gotho-Frisian

wurts, terps and half-timber longhouses

§

Dome-shaped beehive huts

§

Irregular

multi-peaked marquee nomadic tents

·

Epi-Aurignacian

tepees and pile-dwellings

·

Bascoid Cyclopean megalithic

architecture

·

Megalithic

tombstones and tholoi graves

·

Lapponoids’ lean-to and semidugout pit-house

·

Turcoid

dwellings and burials in rockcut caves

|

ANCIENT SETTLEMENTS §

Lakeland,

marshland, lowland, grassland and desert ecosystems §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites

in oases of subtropical shrublands §

Multicellular

labyrinths in arid subtropical lowland §

Tell-sites in

oases of subtropical shrublands §

Oppidans:

hillforts towering on high rock promontories §

Getic boroughs:

villages in alluvial lowlands §

Palatial poleis

and cultic spas in seaside harbours §

Straight streets

and alleys of lake-dwellings |

|

|

|||

|

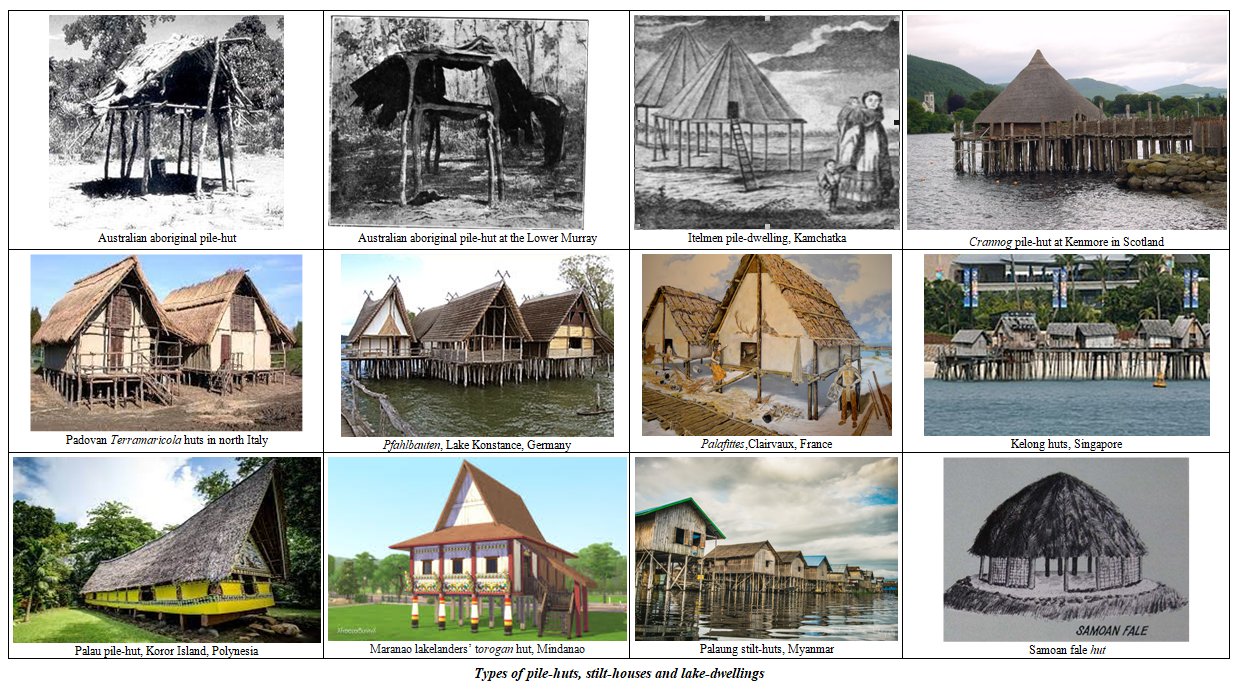

Lake-Dwellings

Pile-dwellings. The origins of

Levalloisian architecture can be reconstructed ex post from

Aurignacian finds. M. M. Gerasimov reconstructed successfully a number of

Late Palaeolithic huts in Siberia (Malta), whose originators were Aurignacian

tribes. I. G. Shovkoplias made a reconstruction of similar round huts in the

Ukraine (Mezin). These habitations were quadrangular or polygonal pyramid

tents (tepees) supported by a construction

of with tall piles crossed on their top and tied with a bast rope (Jelínek 1972: 250, 267). The conic roof was

covered with fells and hides, whose lower fringes were weighed down with

heavy stones. Some tents had a circular design and had an asymmetric roof

leaning to the entrance. Close kinship with microlith tribes was manifested

in a similar architecture of Magdalenian pile-dwellings that differed

from Aurignacian types by having lower asymmetric roofs, shorter piles and a

circular wreath of surrounding stone stabs. On the other hand, Aurignacian

pile-dwellings were of design almost identical to the Tungus chum

and the North American Indian tepee. Their conic construction was very

steep, the piles were extremely tall, the top ends overtopped a lot their

crossing and the basement consisted of a circular wreath of plain stones.

Both abodes were built by fishermen as temporary summertime shelters on the

waterside but in the Neolithic they turned into waterlogged pile-huts

intended for permanent living. Piles hammered into the lakebed or into the

bed of boggy marshes served for insulation from water and humidity. The first

Levalloisians wandering to Southeast Asia could live as fishermen in the

marshland by making tree-dwellings with nests from boughs and piles in

their crown. Pile-houses. Neolithic Europe was

peopled by a race of lake-dwellers, who built their huts on platforms set on

many piles in the middle of a lake or on a lakeshore. The earliest record of

a settlement with pile-houses on an island amidst the marshes comes from Nea

Nicomedeia on the Vistritsa river from (its radiocarbon dates were from 6,063

to 5,834 BC). Its inhabitants combined fishing with agriculture and keeping

goats (Mongait 1973: 206). The site might have been occupied by ancestors of

the Macedonian Paeones, who were

attacked by Dareios and described by Herodot: ‘In the centre of the lake is a

timbered scaffolding on high piers, accessible over one narrow footbridge ...

They get these stakes from the Orbelos mountains and whoever gets married

drives three stakes into the lake-ground for each of his wives. They live in

huts built on the scaffolding and every hut can be entered only over a

drawbridge projecting above the water. Little babies are tied up with a rope

by their legs in fear lest they should fall down into the water’ (Herodot, Hist.

V, 16). The ethnonym is suggestive of Paion,

a divine healer on the Olympus of Apollo's and Asklepios’ stock. Lake-dwellings were most common in the cultures ranging as a

long belt of lakes from Austria to Belgium. The pile-houses began to appear

at Ljubljansko Blat belonging to the Vuèedol culture and continued with the Mondsee culture excavated on Lake

Mondsee (Sharfling). It included sites on Lake Attersee and finds at Rainberg

near Salzburg. The next station was the Altheim group found near

Landhut in Bavaria. Its settlement was surrounded by three concentric rings

of ditches and palisades (Bray, Trump 1982: 14). The continuous belt of lake

cultures with pile-dwellings ended with the Michelsberg culture reaching as far as Belgium. Another parallel

belt headed for Italy and split in Switzerland. Its main station was situated in the Lagozza culture of northern Italy related to a few smaller groups

in central and southern parts of the peninsula. The Swiss settlements

included the Egolzwil centre near

Luzern, the Horgen group on Zürichsee and the Cortaillod sites on Neuchâtel.

The Horgen group bore resemblance to the Seine-Oise-Marne

culture in northern France, while the Cortaillod

localities seemed affiliated to the Chassey

culture in southeast

France. The former two cultures tended to bury their dead in rock-cuts caves

and should be classified as Epi-Tardenoisian. The latter two group lay on the

belt of Epi-Aurignacian cultures and should be attributed to the Celtic

Belgae. Cave-dwellings were very common also in the Chassey localities,

because they covered deeper Azilian layers. The Chassean custom of inhuming

dead bodies in burial caves links them with the Seine-Oise-Marne culture and rock-cut tombs common in the

Phoenician world. Their heritage was due to Mesolithic microlith peoples. It

associated the Hebrew with the Iberians in southwest Europe and the Eburones

in Belgium. Their artificial caves were cut into soft rocks to form large

chambers with niches. They became very common on Sardinia, at the lakeside of

Chalain in the Jura, in the Paris basins and Burgundy (Whitehouse 1975). The Chasseans exhibited a very dense but incompact

distribution, their settlements were scattered in many isolated groups. One

group pursued the southern track to the Garonne basin, whereas the mainstream

followed the northern track to the Seine Basin and Brittany (Piggott 1974:

111; Vogt 1955). The radiocarbon dating reckons with a period from 3,600 to

3,000 BC. Their origin is sought in a westward colonisation from Italy

(Vouga 1934). Their burial customs indulged in digging pit graves or trench

and chamber graves. Terramaricoli. In Italy the

rock-cut caves flourished from 2,500 to 1,700 BC and their builders never

became extinct. The Bronze Age lake-dwellings had a similar distribution but

their area was shifted a little bit more westward. The Swiss lake-dwellings

on Bieler See and Lac du Bourget contained much bronze industry. In northern

Italy these pile-houses were built in the marshes on wooden platforms

surrounded by artificial ditches and lakes so that they survived to posterity

as heaps of black soil with organic garbage refuse (Pulgram 1958). The terramara

finds (Plur. terremare) were unearthed also in the Alföld and Tószög terremare

with heaps of garbage along the rivers in the eastern end. Their origin must

be due to lake-dwellers mixed with Urnfielders. Palafitticoli. On Lago Isolino

and Lago di Varese we find more traditional lake-dwellings palafitte with almost unbroken records

from the Neolithic period. Palafitta (Plur. palafitte) is a local name for pile-houses built on wooden

platforms and waterlogged sites of the Lagozza culture. Best-preserved

remains come from Castione dei Marchesi, Casarodole and Roteglia. Their

Bronze Age heir was the Polada culture on the southern end of Lake Garda in

north Italy. The list of their alleged inhabitants palafitticoli and terramaricoli

is too impressive to quote but it counts mostly with the Ligures,

Piceni, Italiotes and Celts. Crannog. While most

pile-houses on the continent drew away about 300 or 500 m from shores, crannogs in the British Isles stood on

artificial wooden islands. Long piers were hammered into the bottom of lakes

and marshes to support a wooden waterlogged platform and surrounded by a

timber palisade. Crannogs are found

in Britain (Pickering, Somerset), Scotland (Galloway, Ayrshire, Clyde valley)

as well as Ireland (Lagore Crannog, Lisnacroghera). Most of them come from

the Iron Age or are of Early Christian date. Being relatively small, they

must have been inhabited by single families seeking protection from dangerous

intruders. ‘The oldest examples in Ireland have yielded early Neolithic

material’ with Bann flakes (Bray, Trump 1982: 68). Another group of pile-dwellings is known from Wissmar in

Mecklenburg and Gägelow near Schwerin. Vineta and Biskupin are towns of

pile-dwellings, allegedly from Slavonic times, but they probably conceal an

earlier substratum from the Iron Age. Their originators may have been the Pluni, Ploni or Polani, who could have their hand also in the similar Poznañ group. Their villages have long rows of houses

along the waterside and the long central lane. In Africa a group of Bantu peoples use pile-houses that have

developed from lake-dwellings. Their distribution in eastern and southeast

Africa betrays a common starting-point in the Levalloisian or Pre-Aurignacian

colonisation. Their architecture is based on pile constructions, wooden

platforms and conic roofs. The tribes Fon, Luba, Zande, Vongera, Male and

Mogadisha in East Africa use it for building their homes and dry granaries

protected from water. |

Talang. When the Tungus

tribes traversed China and the Philippines, they flooded the shores of

southern seas with their conic tepees that gradually transformed into

seaside and riverside pile-houses. Typical lake-dwellings were rather rare

but almost every waterside in Vietnam, Malaya and Indochina was rimmed by

local pile-houses. They inhabitants lived on the water, travelled on it and

used it also as a dump. The most primitive forms of pile-huts made appearance

in Malaya and in Austronesia. The Dayaks built high platforms on high piles

and approached them by ladders. Their huts were long houses for large

matriarchal families. The Malays lived in stilt-houses called talang that

were built in secluded places. Both tribes were remarkable for fishing

skills, seafaring and their piracy. They slept on mats and used swords for

self-defence. The Papuans in New Guinea built pile-dwellings on logs that

were 5 or 6 metres tall (Vlach 1913: 127). Raft-dwellings. Also the Siamese were wont to live on the water,

but their dwellings floated on the water surface as rafts. The Khao had

stilt-dwellings with stilts projecting above the earth. Their granaries were

made of live trees hanged by wooden platforms. The Annamites in Vietnam used

both raft-dwellings and stilt-dwellings. In America the classic lake-dwellings are not very common,

they were common only to the Olmecs, Chavin and Aztecs, who lived on the

lakeshores and earned their living by fishing. The Paumara in Venezuela

constructed floating rafts out of reeds. The Chavín and Olmecs are suspected

to be a lost colony of the Phoenician seafarers, who came via the Atlantic

Ocean. The Mexican Aztecs had taken over their tall tepees patterns

from the Uto-Aztecan tribes of North America. The Haida, Nootka and other

Salish tribes in British Columbia abandoned such tepees and built

large rectangular pile-dwellings made from wooden platforms and long boards.

Tree-Dwellers. Southeast Asia is inhabited by residual

populations of primitive fishermen, whose culture cannot be explained by

Mesolithic migrations. These populations live in trees, make nest from

intertwined boughs in their crowns and access them by climbing up steep

ladders. In South India the long stilt-dwellings in the trees are erected by

the Kanikkarar. In China the Miao-tse were said to live in rock caves in

winter and in tree-dwellings in summer (Buschan 1923: 540, 641). The dwarfish

Senoi and Semang belonged to the Malaysian Negritos but their culture was

influenced by prehistoric Proto-Malays to such an extent that they combined

living in rock-caves with summertime relaxation in tree-dwellings. They

average 155 cm in height but contains a strong admixture of Mongolian blood

(Buschan 1923: 540, 641).

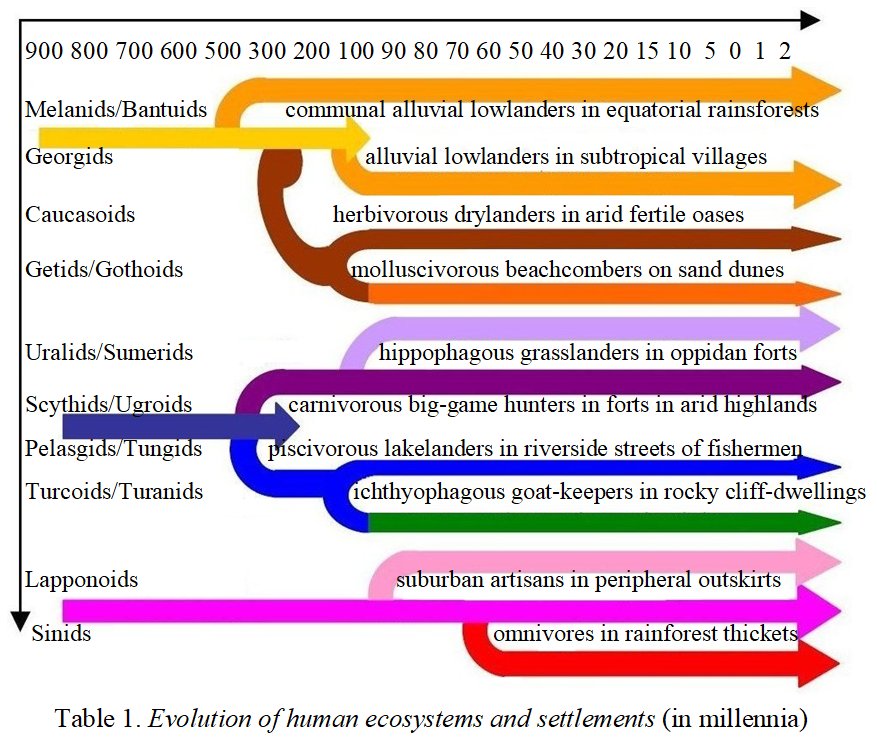

Table 1. Stilt-dwellings

at the waterside Vako. Also the Garo

used tree-dwellings for summertime habitation. The Naga used them only for

their sentries as guarding huts. The Karen in Burma fled to them temporarily

when staying outside far from their homes on harvest tours. In New Guinea the

Kai tribe built tall tree-huts with long ladders. Similar huts were built by

the Battaks in Sumatra who combined them with pile dwellings constructed on

high wooden platforms. The fishermen’s tribes in the Solomon Islands built

their tree-dwelling vako when menaced by foes. The aborigines on the

Isle of Isabelle lived in tree-dwellings that towered 25 to 30 metres above

the ground. They accessed them by means of long ladders (Vlach 1913: 38). Extract from Pavel Bìlíèek: Prehistoric Dialects II. Prague 2004,

p. 580-584 |

|||||||