|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

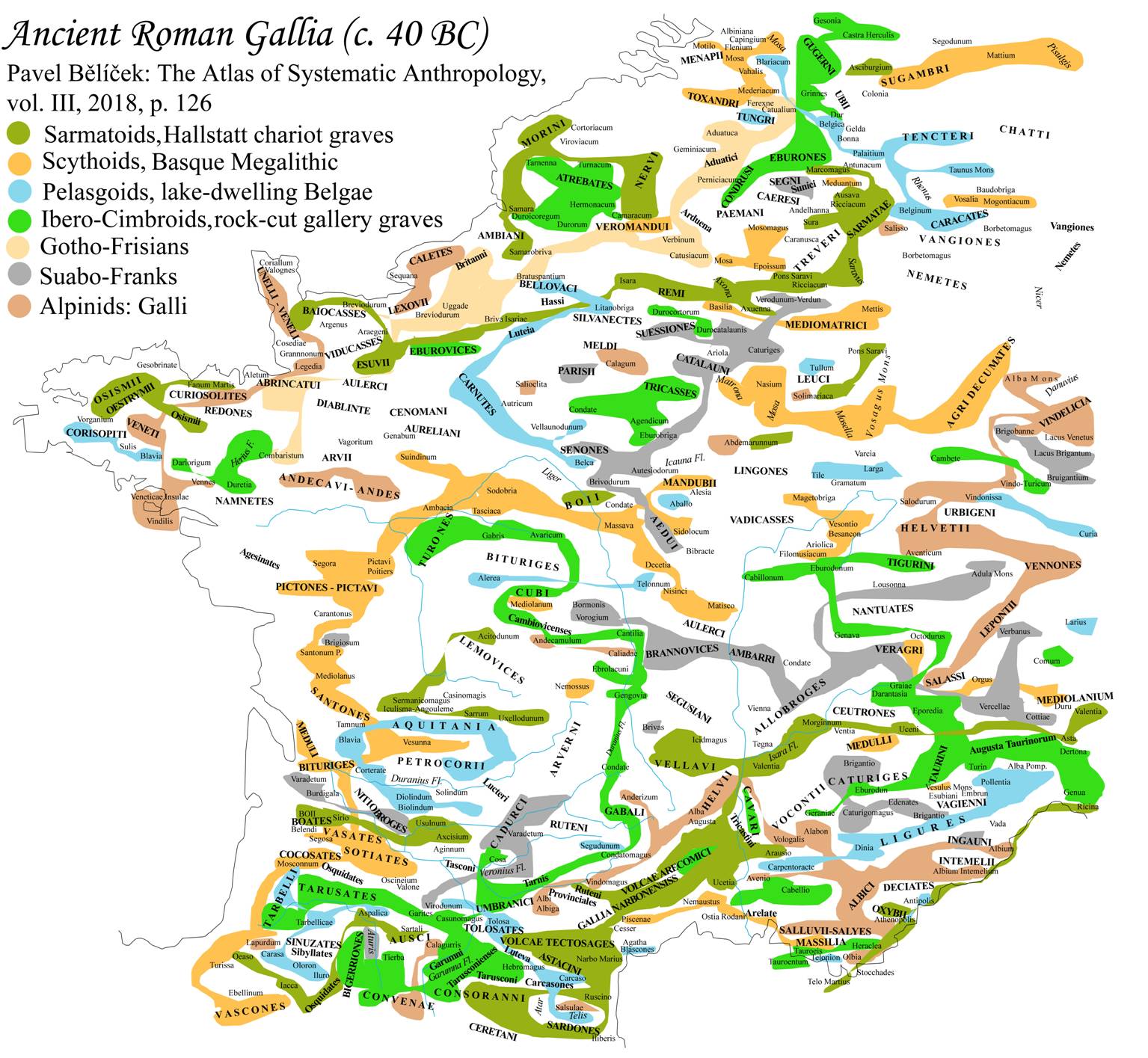

The

tribes of ancient Gallia The clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient Gauls (from P. Bělíček: The Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, 2018, p. 126) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

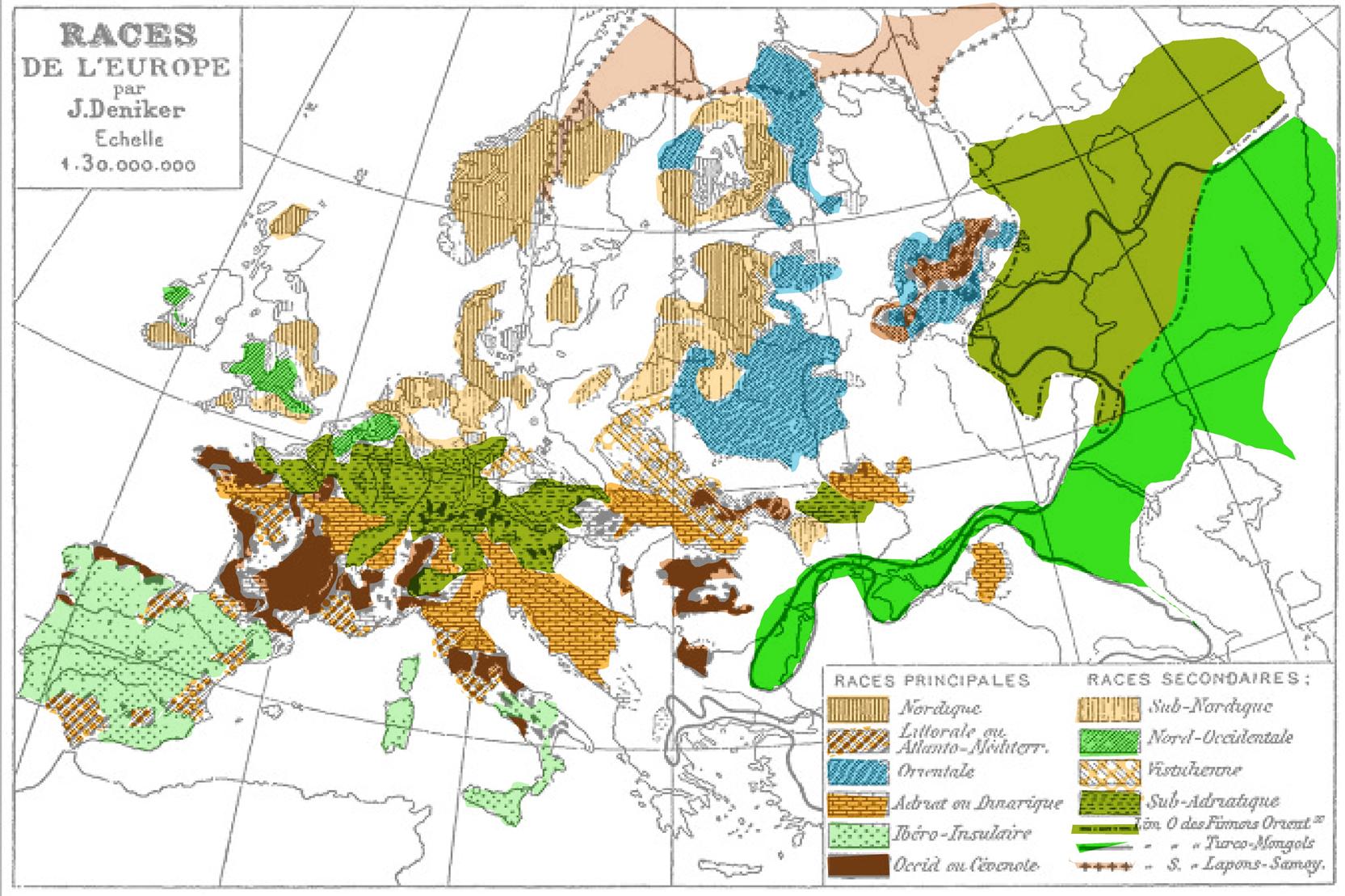

Map 32.

Racial map of Legend to Map 32:

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

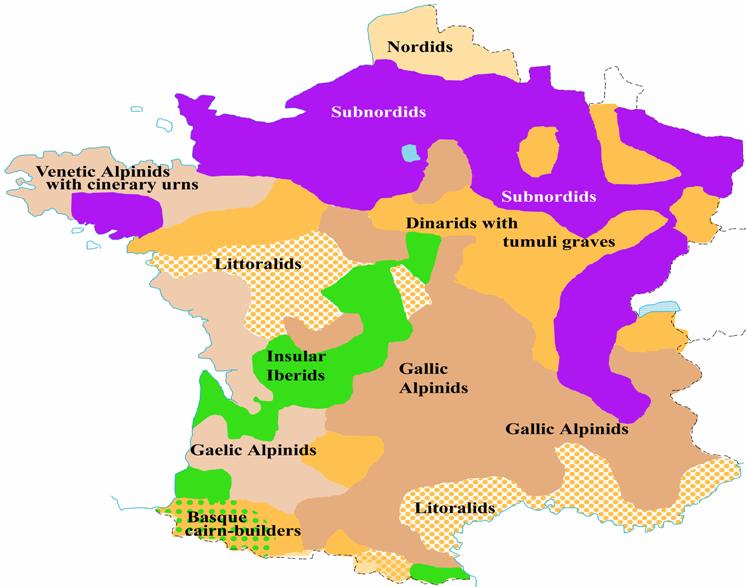

Tab 33. The

distribution of races in France (after G. Montadon)

The Archaeological Disambiguation of

Ancient Romance Tribes

The complex of Romance

peoples calls for a detailed dissection that might elucidate the anatomy of

their inner ethnic factions. The very term ‘Romance’ is a controversial

misnomer because its originators were the Roman Marsi,

Sabini and Samnites,

who descended from the Hallstatt horseback riders

of Sarmatian origin. They imported the advanced

Iron Age metallurgy to Hallstatt Sarmatids were not populous enough to give the IE

language structures a definite Iranian and Uralic stamp, and so they were

soon outnumbered by Gallic Celts and Iberian Mediterranids.

As a result, in Italic, Gallic and Iberian languages the strong Celtic

element prevails over Sarmatic

peculiarities. When we abandon the pointless concept of the Romance family, it may

be replaced by more suitable terms of Gallo-Romans of Tardigravettian

origin. Its complex may however be analysed also as a part of the Epi-Aterian family or Epi-Magdalenian

domain. Arguments for the former solution are that Arabic, Iberian and Italic

languages group share one category of determination with very similar systems

of definite and indefinite articles: French le, la

– un, une and Italic il, lo – uno

as compared to Arabic al- or el

– -n. Articles represented a typical non-IE import of

European Bascoid megalith-builders, who shared k-plurals

and definite articles in -k with Abkhaz kurgan-builders.

Epi-Aterians. The idea of Epi-Aterian family or Basco-Scottish

family is based on the structural unity of West-European megalith cultures,

whose patterns were closely associated with the Berber megalithic complex in Another viewpoint open to disputes

speculates that the Chalcolithic megalithic

builders may be remote descendants of the Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician, Solutrean, Aterian, Szeletian people of

Mousterian origin. They lived in caves, applied leaf-shaped lance-heads and

buried the dead under piles of stones in front of their cave abodes. These

cavemen were immiserated hosts of mammoth-hunters

who wandered in quest for their herds to Mario Alinei’s

Palaeolithic Survival theories have breathed new life into diffusionist thought and make it possible to link

prehistoric ancestors with modern survivors. They consider links between Aterians (30,000 BC), Basques and Berbers, who developed

similar leaf-shaped lance-heads and funeral architecture with round

dome-shaped mounds. Leaf-shaped points were cultivated also by Solutrean horse-hunters (18,000 BC) and flourished also

in Lincombian, Ranisian and Jerzmanowician sites (43,000 BC) in

The predecessors of western megalith-builders may have colonised their

Atlantic sites in waves of several prehistoric colonisations: * Aterian (c. 145,000 BP – 30,000 BP)

was a Middle Stone Age industry jutting out of * Mousterians (70,000 BP) represented a

Neanderthal culture extending from western * Châtelperronian

(44,500 – 36,000 BP) was formed by a Mousteroid

culture of denticulate tools that were situated in * Solutrean (22,000 BP), a culture of horse hunters with

leaf-shaped and pressure-flaked industry. It was located in western * The advent of the La Hoguette megalithic culture (4900 BC) in * The Andalusian Neolithic (c. 4800 BC)

introduced the first dolmen tombs in southeast * The Chalcolithic Almerian culture (3600 BC) with megalith constructions that

were lining the eastern coasts of * The Los Millares culture (2900 BC) developed a higher stage of the Almerian tradition of megalith-building architecture as

its direct descendant. It prided on large concentric cupola-shaped mounds. *

The VNSP or Castro of Vila Nova de São

Pedro culture (2700 BC) exhibited the mainstream of Iberian

megalithic cultures importing the typical castro

type of fortified oppida. Its architecture gave

preference to circular roundhouses with round walls roofed by conical wooden

construction. *

The nuraghe (Sardininia, 1900 BC) and

talaiot ( |

|

Franco-Swabian

Dolichocephalous Littoralids Franco-Swabian dolichocephals. As far as populousness is concerned, the

second position in the census of Campignian

Littoralids. Epi-Aurignacian fishers searched for lakes in lacustrine localities

and plain depressions below sea level, whereas Epi-Cardial fishers contented

themselves with seaside deep water shores suitable for harbours. Cimbrian,

Etruscan and Punic pirates preferred rocky cliff-dwellings along narrow

straits and dolichocephalous Littoralids favoured sand dune beaches full of washed-up shellfish.

Archaeologists pay less heed to their Late Mesolithic predecessors denoted as

Campignians (12,000 BP). Their type site was situated in Le Campigny along the Seine Inférieure.1 Its nearest relatives were found in

the Asturian culture (9280 BP) settled

in Eastern Austuria and Western Cantabria. Asturian sites were linked

with the contemporary Muge culture in the Tagus Valley in Portugal. Both

localities were noticeable for finds of pick-axes, whose heads were attached in a perpendicular

direction to the handle. Another

typical product of Campignians was the large

hand-axe that gave them the nickname of ‘men of the halberd’.2 The second phase of

the Campignian civilisation is referred to as Robenhausean culture. Its

typical left-overs were shell-middens, known as kjökkenmöddinger in Denmark in Spain and as concheros in Spain. They looked like heaps

of waste and kitchen refuse thrown out of windows of longhouses. Its debris

were piled up and formed mounds of sand dunes dubbed as ‘raised

beach’. This life-style characterised

them as beachcombers and shellfish eaters. Their northern outposts were excavated in the Nøstvit culture near Antrim beech in south

Norway. Their westernmost seats were dug up in the

The inner taxonomy of Gothoid tribes may be

set up by using data of population genetics. According to the high rates of

the Y-DNA haplogroups I1 and I2 in Map 34, it is

possible to distinguish several filial plantations of Neolithic farmers with

the Y-haplotype I. Their leading dominant was

formed by the Danubian Linear Band Culture with the

haplotype I2. Its people managed to avoid Germanisation

brought about the avalanche of Tardenoisian and Beuronian

microlithic cultures from the east. They were IE Gothids preserved under the umbrella of Slavonic Subnordids. Their fraternal civilisations with the Y-DNA

J operated in southern The

Phenotypes of Racial Groups in

French anthropology

was studied in detail by the famous naturalist Joseph Deniker

of Russian origin. He opposed racism and proposed to treat races as equal

nationalities and ethnic tribes. In his Races et peuples de la terre (1900) he

classified Iberian Mediterranids as race

ibéro-insulaire, Alpinids as race cévenole

and Franco-Swabians on coastlines of the Balearic

and Epi-Cardial Fishers. The southern parts of Epi-Aurignacian Mediterranids. Descendants of Aurignacian colonisations differed from the Epi-Cardial progeny by constructing rectangular

stilt-huts and post-dwellings. Such a rectangular make-up characterised

especially the Chasséen complex (4500-3500 BC). It got

its name from the type site near Chassey-le-Camp in the

Saône-et-Loire department. Its architecture with dammed settlements on

vertical piers and platforms on horizontal trunks looked similar

to two contemporary Swiss groups: the Cortaillod Culture (4300-3900 BC) in

the west and the Pfyn assemblage (3900-3500 BC) in the east. Their daugherly

derivations appeared in the Lombardian and Venetian Polada culture (2200

to 1500 BC). Its younger continuation

loomed in the Terramare technocomplex (1700-1150 BC) in the Bell-Beaker Folk. Campignian shell-fish eaters later turned into the

culturally advanced Bell-Beaker Folk and Franco-Swabian

frog-eaters. Their seats and travels are sketched in Map 31. It illustrates

the spread of the Beaker Folk by terms of chronological data in violet

colour. In addition, it matches its tribal colonies (orange colour)

with ethnonymic groupings recorded in maps by

Ancient Roman geographers (black colour). The

Beaker Folk lived in long communal houses and excelled in high maritime

mobility. Their beachcombing life-style promulgated the Gothoid

white-skinned race and campaniforme pottery along

the eastern coastline of African as far the Cap of God Hope. About 2500 BC

their hosts landed on the

Trichterbecherkultur. The Beaker Folk settlements often ran across the sites of the

Funnelbeaker culture (Trichterbecherkultur, 4300 BC) in North Europe.

Its core seems to have grown out of the local Gothoid handaxe traditions and

suggests association with the Rugians. Their ceramic style was soon affected by the influx of

megalithic dolmen burials inspired by techniques of the Globular Ware

pottery. Its main tribal branches are linked with ancient Rugii

and Pomeranian Rugini. In Britain they left several

promising ethnonyms such as Ragae and Rigodunum. Since their phratries often

included the tribes of Senones, they may be associated with the

British Cenimagmi. One of their affiliated clans resided also in the Seine-et-Marne department. Megalith mounds have to be considered as a

higher stage of simple pile-burials and straw beehive huts in the period when

Scythoid chieftains began to subdue neighbouring

tribes and acquire greater social influence. They spread from Campignian Littoralids. The first Gothids with the Y-haplogroup

I1 came to

|

|

|||||||||||||||