|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

The Systematic Anthropology of

Human Varieties Clickable terms are red

on the yellow or green background |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

The Theoretical Foundations of

Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistoric Studies |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

Evolutionary Paragenesis as a

|

|

The basic

primary prototype of human species was the black ulotrichous equatorial race,

whose primary seat lay in the tropical rainforests of The most urgent theoretical requirement of

prehistoric studies is to abandon the dogmatic Extinction Theory and replace

it by the flexible accounts of Alinei’s Palaeolithic Survival Theory. It

argues that the human past is not forever dead but it continues to survive in

our blood and chromosomes. Inheritance does not jump wildly by mutations from

one genus to another but preserves all previous mutations and engenders new

subordinated varieties as its subclades. It presupposes the principle of racial interfertility2 maintained by the

so-called ring species (German Rassenkreise)3

admitting temporary mixed mating. Such ring species unite series of early

populations, which can primarily interbreed with each other but later they

fail to beget crossbreds. After a longer period of adaptive speciation and

adding new and new specific mutations they cease to be interfertile races. Such dilemma befell the genus of Australopithecinae, who acted as an in-between linking open-air hominins with rain-forest hominids. Either they were pulled down into the local or regional gene flow between neighbouring populations or they separated from their mainstream and restored cohabitation with the backward rainforest species. At first they coexisted as interbreedable races but millennia of adaptive isolation made them speciate into a diverse species and genus. Such a model of genetic mating sheds new light on the beginnings of all hominids and hominins. It means that all binomial designations in the genus Homo could live together as interbreedable subspecies or racial varieties, whereas Paranthropinae and Australopithecinae lost contact and underwent regressive mutations due to return to the rainforest thicket. |

||||

|

The Paragenetic Model of Evolution The paragenetic model of prehistory

presupposes that most hominins and hominids lived in relative interbreeding

and their genetic distances were much nearer than now. What we denote as

detached genera and species were actually interfertile genetic races,

strains, lineages, crosses and hybrids that later lost mutual interfertility

owing to isolation in different hominoid populations. It is not plausible

that they developed by large jumps from one genus to another, they must have

maintained and preserved their genetic pool through progressive evolutionary

metamorphoses. Many categories of genus and species were only generations, so

the extant binomial and trinomial anthropological classification should adopt

a special term for transient generations. All strains underwent parallel

processes of hominisation, gracilisation and sapientisation by means of

radical revolutions and longer stages of conservative inertia. Hominins split

off hominids and hominoids as a special genetic stream competing with

alternative strains of Paranthropines and Australopithecines. Participation

in different population strains caused intraspecial differentiation. In the

following evolutionary series the symbol means digression while the arrow → implies genetic continuity. It

does not mean direct mother-daugher inheritance but a complex statistic

process with many digressions splitting off the dominant mainstream. The

following series are chief statistic mainstreams that suggest that the

Palaeolithic Urrassen had different ancestors but converged to one of

predominant Neolithic racial varieties.

Tall robust

dolichocephalous herbivores with marked crista sagittalis Gigantopithecus

(9 mya) → Ouranopithecus

(9 mya) ( Gorillas (9 mya)) → Paranthropus aethiopicus

(2.5 mya) ( Paranthropus robustus (2

mya)) → Australopithecus

garhi (2.5 mya) → Australopithecus sediba (1.8

mya) → Homo gautengensis (1.8

mya) → Homo

erectus (1.8 mya) → Oldowans (1.8

mya). Slender

piscivores with tall and leptoprosopic flattish faces: Proconsul africanus (23 mya) → Kenyanthropus platyops (3.5 mya) → Australopithecus

afarensis (3.9–2.9 mya) → Homo habilis (2.1–1.5 mya) → Homo

rudolfensis (2–1.5 mya) → Levalloisians (0.5 mya). Tall

brachycephalous carnivores and big-game hunters with narrow aquiline noses Australopithecus anamensis (4.5 mya) → Laetoli man → Homo heidebergensis → Homo rhodensis (0.5 mya) ( Saldanha

man) → Homo neanderthalensis → Mousterians. Shortsized brachycephalous omnivores: Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4

mya) → Ardipithecus kadabba ( Pan

paniscus (Bonobo)) → Australo-pithecus

afarensis (3.9 mya) → Homo habilis → Sanids → Pygmids

( Homo floresiensis) → Sinids.

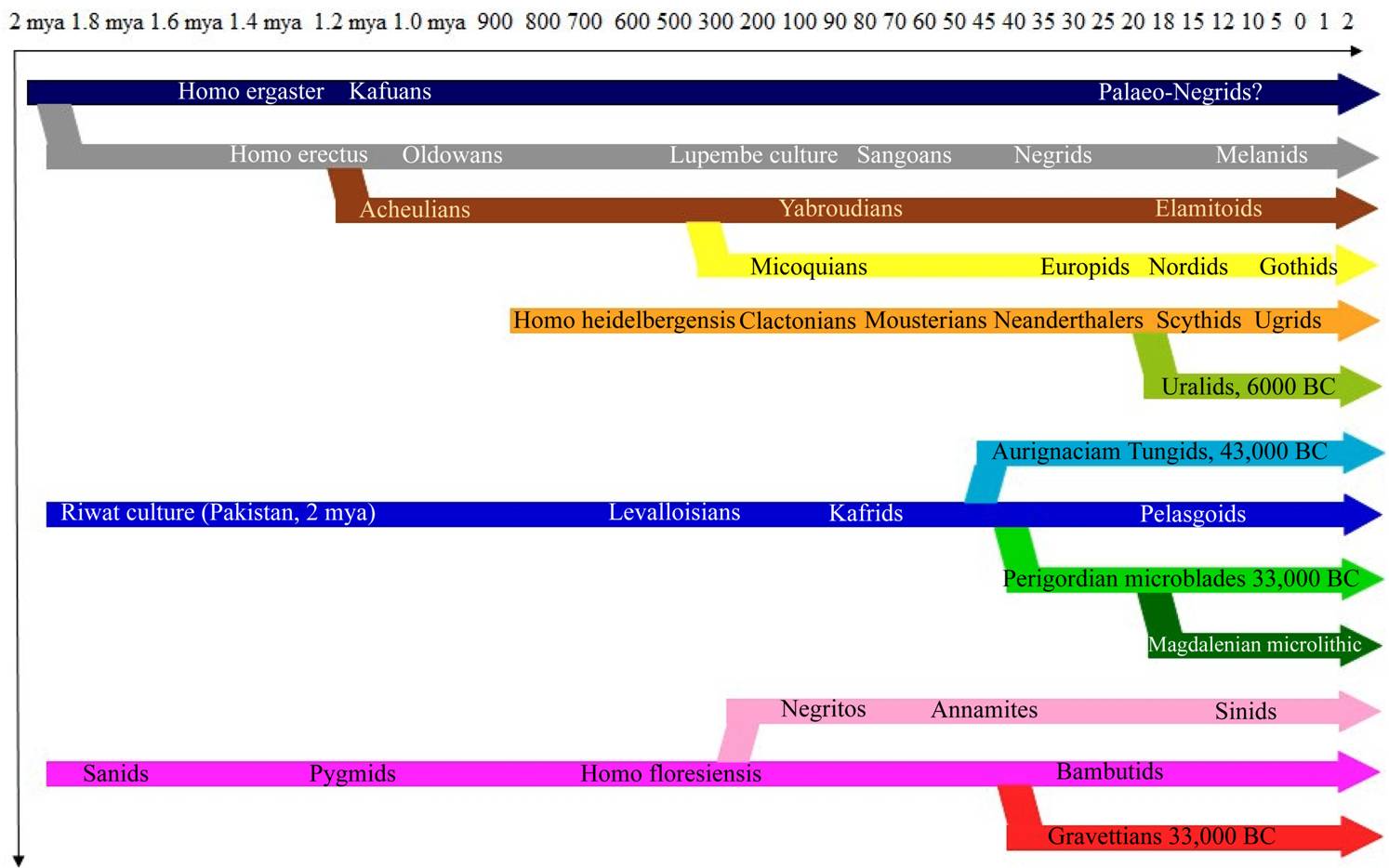

Table 1. The paragenetic

model of racial diversification |

|

|||||

|

|

The Phylogenetic

Trees of Human Stocks

Our Palaeolithic ancestors will remain doubtable mythical chimaeras

until they are identified with real living races surviving to our days. Table

8 outlines the quadripartition of four basic human stocks and elucidates

their rough evolutionary branching along the axis of time. Its genealogical

graph outlines probable successive bifurcation but cannot specify very

precise chronology in thousands of years. Its scheme suggests that axe-tool

cultures gradually split into four robust tall races with dolichocephalous

skulls and the blood group O. Their inner subclasses corresponded to several

well-known archaeological cultures of Oldowan chopping-tool makers and

Acheulean hand-axe manufacturers. Their colonists pursued the equatorial line

of the tropical rainforests, and even though their Caucasoid and Nordic

progeny diverged to colder northern regions, they all remained faithful to

herbivorous nutrition. Their stocks developed from plant-gathering cultures

with hand-choppers, ate corn seeds and vegetal roots and showed inclination

to preagriculturalist or agriculturalist economy.

Table 8 sketches a model of the probable phylogeny of human cultures

that counts with four principal independent lineages of development. They

divide prehistoric cultures into equatorial stocks with hand-axes, Altaic

tribes with flake-tool industry and Lapponoid ethnic groups with cremation

rites. The first phylum gave rise to the hand-axe cultures of

agriculturalists and gatherers of vegetal plant crops that fell into the

branches of Negrids, Melanesids and Australoids. They formed cultures of

robust tall-statured dolichocephalous herbivores (robust plant-eaters)

of the black equatorial race. The main stream of Oldowan

colonists headed eastward for the tropical rainforests of These ethnic cultures propagated by

eastward setting out on Oldowan, Acheulean, Abbevillian or Micoquian migrations

that spread the art of manufacturing various types of choppers and hand-axes.

One of their branches colonised the southern margins of A similar evolutionary

account may be sketched for the Altaic Mongolids. Reliable dates for

their prehistory are missing but a lot can be deduced indirectly by comparing

their archaeological cultures. Asiatic Mongolids may be divided into big-game

hunters and fishermen with additional small-game hunting subsistence. Altaic

hunters probably descended from the Mousterian mammoth hunters butchering

giant mammals with long lances provided with leaf-shaped (lanceolithic)

heads. The faction of Altaic nomadic fishermen evolved into the progeny of

Levalloisian Neanderthalers specialised in making long pointed leptolithic

flake-tools determined for spearheads harpooning fish. Their descendants were

the Aurignacians with long prismatic knives. Another group separated as the

microlithic family with tiny microlithic flakes set into arrows and wooden

hafts (Magdalenians, Maglemosians, Azilians, Tardenoisians). Aurignacians can

be identified as Tungids of Combe Capelle type, the latter seem

to betray members of the Turanid family of Turcoid provenance.

Both offshoots tend to display a conspicuous predominance of the blood group

B. The big-game hunters of the megalithic extraction, who comprise Basques,

Berbers, Abkhaz, Scythians and Ugrians, made an exception. Owing to

contamination they exhibit the blood group O with the negative Rh factor.

What they preserved as their specialty, was the Y-DNA haplogroup Q and the

mtDNA haplotype X. If Mousterians and Levalloisians grew out of common

ancestry, the four-stock model may shrink into a mere tripartition. Most Lapponoid

and Pygmoid races abound in the blood group A and bear strong

resemblance to the Annamite short-sized ethnovariety that fathers also

Negritos and Tasmanians. The Austronesian dark-skinned Negritos with

cremation burials, semidugouts and lean-to shelters probably arose due to a

huge colonisation from |

|

A numerous population

of Lapponoid tribesmen settled down in the Indian subcontinent and gave local

autochthons the stamp of incinerating cultures. Their cremations took place

on funeral pyres in the accompaniment of widows, who were burnt lying beside

their husbands. Their impact is discernible also in the Andronovo cremation

culture (15,000 BC) excavated in A similar evolutionary

account may be sketched for the Altaic Mongolids. Reliable dates for

their prehistory are missing but a lot can be deduced indirectly by comparing

their archaeological cultures. Asiatic Mongolids may be divided into big-game

hunters and fishermen with additional small-game hunting subsistence. Altaic

hunters probably descended from the Mousterian mammoth hunters butchering

giant mammals with long lances provided with leaf-shaped (lanceolithic)

heads. The faction of Altaic nomadic fishermen evolved into the progeny of

Levalloisian Neanderthalers specialised in making long pointed leptolithic

flake-tools determined for spearheads harpooning fish. Their descendants were

the Aurignacians with long prismatic knives. Another group separated as the

microlithic family with tiny microlithic flakes set into arrows and wooden

hafts (Magdalenians, Maglemosians, Azilians, Tardenoisians). Aurignacians can

be identified as Tungids of Combe Capelle type, the latter seem

to betray members of the Turanid family of Turcoid provenance.

Both offshoots tend to display a conspicuous predominance of the blood group

B. The big-game hunters of the megalithic extraction, who comprise Basques,

Berbers, Abkhaz, Scythians and Ugrians, made an exception. Owing to

contamination they exhibit the blood group O with the negative Rh factor.

What they preserved as their specialty, was the Y-DNA haplogroup Q and the

mtDNA haplotype X. If Mousterians and Levalloisians grew out of common

ancestry, the four-stock model may shrink into a mere tripartition. Most Lapponoid

and Pygmoid races abound in the blood group A and bear strong

resemblance to the Annamite short-sized ethnovariety that fathers also

Negritos and Tasmanians. The Austronesian dark-skinned Negritos with

cremation burials, semidugouts and lean-to shelters probably arose due to a

huge colonisation from A numerous population of Lapponoid

tribesmen settled down in the Indian subcontinent and gave local autochthons

the stamp of incinerating cultures. Their cremations took place on funeral

pyres in the accompaniment of widows, who were burnt lying beside their husbands.

Their impact is discernible also in the Andronovo cremation culture (15,000

BC) excavated in Extract from P. Bělíček:: The Synthetic Classification of

Human Phenotypes and Varieties Prague 2018, p.

23-25 |

|

||