|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

Racial Varieties in Spain Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

|

|||||||||

|

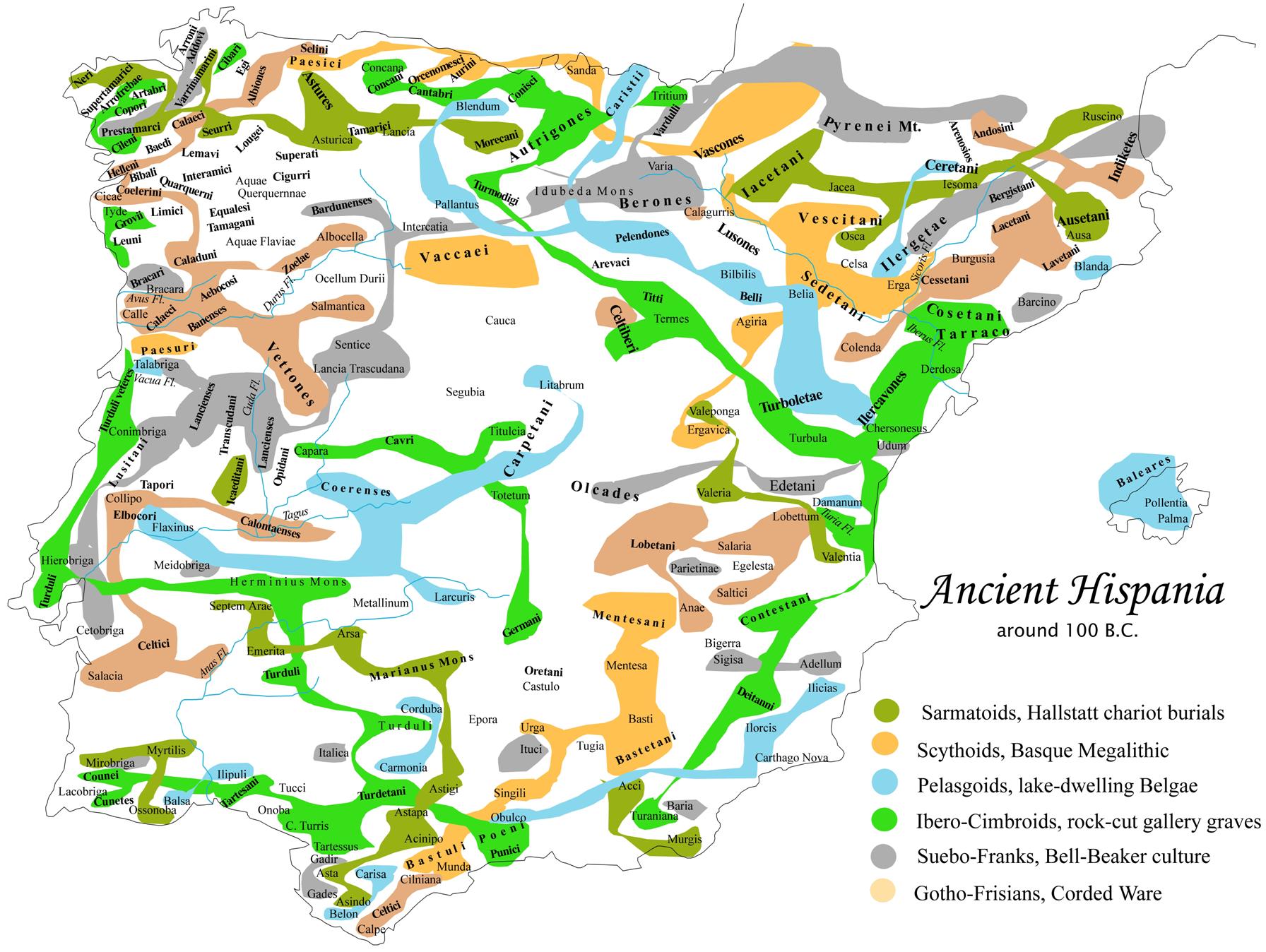

Ancient

tribes and races of Hispania (Pavel Bìlíèek: The

Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, Map 38, p. 134) |

|||

|

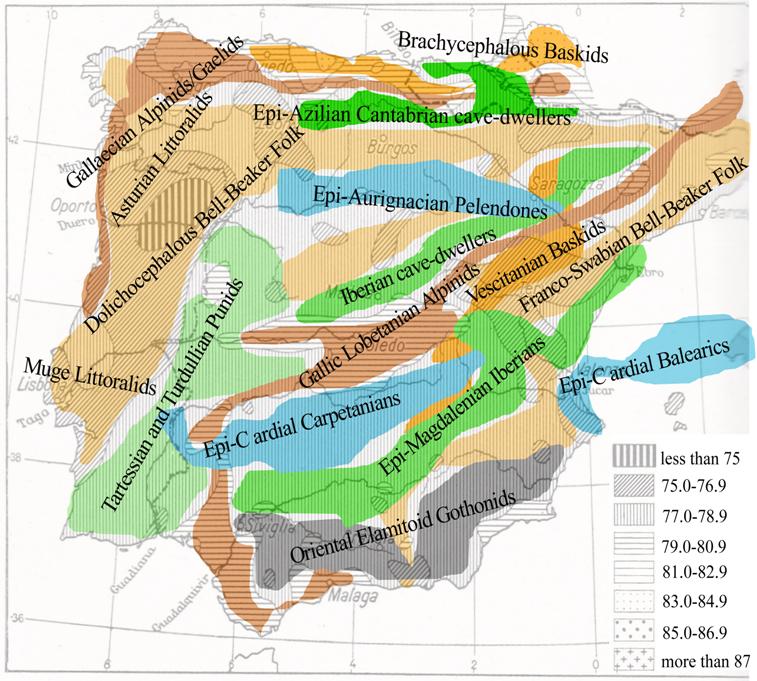

|

Map

36. The racial varieties of the

Bell-Beaker Folk.

The Nordic blond-haired stock was represented by the Franco-Swabian dolicho-cephalous tribes

of tall robust stature and light yellow complexion. Archaeologists knew them

as bearers of the Beaker Folk culture with campaniform

pottery. They had a colony in the Portuguese Muge

culture (8,000 BC) with shell middens on littoral

sand-dunes. Beachcombing and search for shellfish, molluscs, oysters and frog

legs provided them with the ignoble repute of ‘frog-eaters’. The Iberian Muge

culture (8000-4000 BC) was first unearthed from shell midden

sites in the lower valley of the Later

this culture gave rise to the Bell-Beaker Folk culture (2900–1800

BC) that bore

conspicuous resemblance to finds of the Indo-European Corded ware. Its

Portuguese name was cultura do vaso campaniforme and it

showed marked correlation with African littoral cultures. Their migration

travels, however, pursued an opposite direction, they spread from

Gothids. The real Celts did not play the decisive

administrative and military role in prehistoric

Berids. Bertil

Lundman3 introduced a special racial variety

of Berids for ‘small-bodied dolichocephalics’, who probably arose as a result of Alpinisation of Nordic Littoralids

of the Muge type. They bore typical Gothonic traits such as rectangular orbits, keeled vault,

eminent glabella, dolichocephalic

skulls and heavy muscular body. Yet owing to Alpinoid

environment they exhibited shorter stature, low face and rugged appearance.

The French anthropologist R. Riquet classified them

as ‘Méditerranoïdes archéomorphes’ and included them into one larger

grouping together with the Tage-Mugem types in Spain, Aquitanians

and the Brittanic Téviec

and Hoediec in western France.4 Another approach to the issue of Iberian

short-statured dolichocephals

is demonstrated by Joseph Deniker. He proposed to

treat them as a sort of the Ibero-Insular race. A

more common term for their group is the true West-Mediterranean race or Atlanto-Mediterranid race. Such terms for hybrid mesoraces are holistic hold-all phrases for recent racial

phenotypes that originated by intermingling definite Mesolithic and Neolithic

Gothoid archetype with allotypes

adding admixture from their surrounding neighbourhood. A convenient solution

is offered by the method that subtracts all incompatible additions and leaves

alone the archetype eteo-race. Gracile Mediterranids. The term of Mediterranids

itself makes sense only if we separate Tungusoid Leptolithic and Turanid Microlithic cultures in the Mediterranean area. Both

evolved from the stock of Altaic nomadic fishers called Denisovans

or Early Gracile Neanderthals5. Their older Tungusoid

branch consisted from gracile lake-dwellers with

long prismatic blades and knives, their younger Turanid

branch specialised in producing small flakes inlaid into bone hafts. Iberian

anthropology is confused by subtle detailed differences between Gracile and Atlantic Mediterranids,

Trans Mediterranids, Dinaromediterranids

and Eurafricanids. The Eurafricanids

are regarded as an African subtype of Atlanto-Mediterranids and

the Trans Mediterranids are

elucidated as an intermediate type between Euafricanids

and Gracile Mediterranids. Dinaromediterranids are

rated as an intermediate ‘mesorace’

exhibiting Dinaric traits among Mediterranids.

Their distinguishing markers are mostly secondary and obscure their taxonomy: *

Atlantic Mediterranids are

Nordic Franco-Swabian Litteralids

descending from the Beaker Folk. *

Trans Mediterranids are

descendants of Pelasgoid Iberomaurusians

(25,000 BP) and Cyrenaic Dabban

culture (38,000 BC) and their sites range from *

Eurafricanids are harbingers of Turanid

microlith cultures embodied by the North African Capsians (8,000 BC), Hebrew Natufians

and East African Iberians. *

Dinaromediterranids are a mixture of gracile

Epi-Cardial Pelasgids and

Dinaro-Armenids with prominent convex and leptorrhine noses.

Such a conglutination of racial categories can be disentangled only by

reducing their complex to Gracile Mediterranids split into two remotely related lineages:

darker Epi-Cardial Pelasgoids

and lighter Epi-Aurignacian Tungids.

Gracile Mediterranids

display facial appearance with subtle, soft and gracile

features. They are of medium or shorter height and exhibit mesocephalic cranium with a narrow leptoprosopic

face. Their nose is as narrow as is common in hyperleptorrhine

types. Their most conspicuous

traits are small hands and feet. Holistic approaches rate Mediterranids

as a unique compact synchronic unity without realising that they contain

several incompatible ethnic components. Their living progeny represents a hybrid

hold-all abstraction composed from incongruous diluted remains of prehistoric

populations. The ultimate goal of anthropology is to decompose them to

elements corresponding to stocks of Palaeolithic ancestors. The core of Mediterranids is formed by two races of nomadic fishers, Aurignacian Tungids with Leptolithic industry and Madgalenian

Turanids with Microlithic

implements. Aurignacian Tungids

have survived in a patent form in Polonians and

Bulgarians. In a latent form they were absorbed in Chasséen

people and La Tène tribes. Most of them

exhibit gracile and slender appearance with whitish

complexion.

|

Pelasgids. A

special category of Gracile Mediterranids

should be reserved for Epi-Cardinal Pelasgids. Their Y-haplogroup T

is a Euro-African predecessor of the Tungusoid haplotype C and seems to date back to Levalloisian

origins. They must have survived latently in their early ancestors known for

manufacturing knapped flakes from a well-prepared platform. Their southern

tribesmen colonised coastlines of

Elamitoid Bull-Leapers. Andalusian

farmers on the The Spanish invention of agriculture

probably drew inspiration from Iberids. The ancient as well as modern racial dominant of Magdalenian, Turcoid and

Iberian cultural morphology Traditional architecture: rock shelters, rock-cut

graves, caves, cave art, petroglyphs Epi-Magdalenian, Epi-Azilian

and Epi-Tardenoisian Turcoid

languages: [Raetian – Etruscan – Umbrian –

Sicilian] + [Iberian – Celtiberian – Cantabrian] + [Punian – Tartesian – Turdetanian – Turdulian] + [Ivernic ( Eteo-Iberids (Madgalenian

rock shelters, goat-keepers) → Iberi + Celtiberi + Germani + Tavri Etruscoids (funeral rock-cut necropoleis) → Raetians + Etruscans + Umbrians

+ Sicilians Epi-Azilians (cave-abodes, rock shelters, cave

art) → Cantabri

+ Turmodigi

+ Concani + Artabri + Cileni Punids (rock-cut graves) → Punici + Poeni + Tartesani + Turdetani + Turduli + Cunetes + Counei Table

40. The disambiguation of Mesolithic microlith

cultures Tardenoisians. When we exempt Tungusoids

out of the large catch-all term of Mediterranids,

we get Altaic Turanids of three lineages: Maglemosian bog-people (Y-hg R1a), Etruscoid

and Punoid coastlanders and

Magdalenian reindeer hunters (Y-hg R1b). In the Neolithic the former two

tribal branches passed from fishing to seafaring, while the third group of

Magdalenian and Azilian drylanders

switched from reindeer hunting reindeer to goat keeping. The hordes of

Mediterranean Etruscoid coastlanders

probably recruited from the Tardenoisian culture (cca

8000 BC). It did not occupy connected dryland

plantations but joined isolated islets of fishermen’s colonies. They crisscrossed the Rock-cut necropoleis

were built in native Etruscan centre Cerveteri as

well as in Sicilian Pantalica. Their

architectonical style originated in Punids. Phoenicians resembled Etruscans by their addiction

to seafaring in naval piracy but got hold of colonies in southwestern

†Atlanto-Mediterranids. One of confusing misnomers are Atlanto-Mediterranids

because their group arose from the Franco-Swabian

Littoral Nordids and had nothing in common with Epi-Cardial and Epi-Magdalenian

Mediterranids. Their core consisted of Europoid dolichocephals in

contrast to the genuine Mediterranids who were

composed of Altaic mesocephals. When Carleton S. Coon defined Atlanto-Mediterranids,

he wrote: “The face is of medium length and of moderate width; the orbits are

of medium dimensions, and in many instances slope downward and outward, as if

the confines of the face were too narrow for them.” He mentioned their mesocephaly

and compared them to tribes burying their dead in long barrows. He obviously

took over Joseph Deniker’s term ‘race littorale au atlanto-méditerranéene’, which actually applied to the Muge culture of shell midden

and ancestors of the Bell-Beaker Folk. Extract

from Pavel Bìlíèek: The

Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, Map 45, p.

152, pp. 127-136. |

|