|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

The Glottogenesis of Ugro-Scythoid

and Basco-Scandic Languages Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

||||||||||||||

|

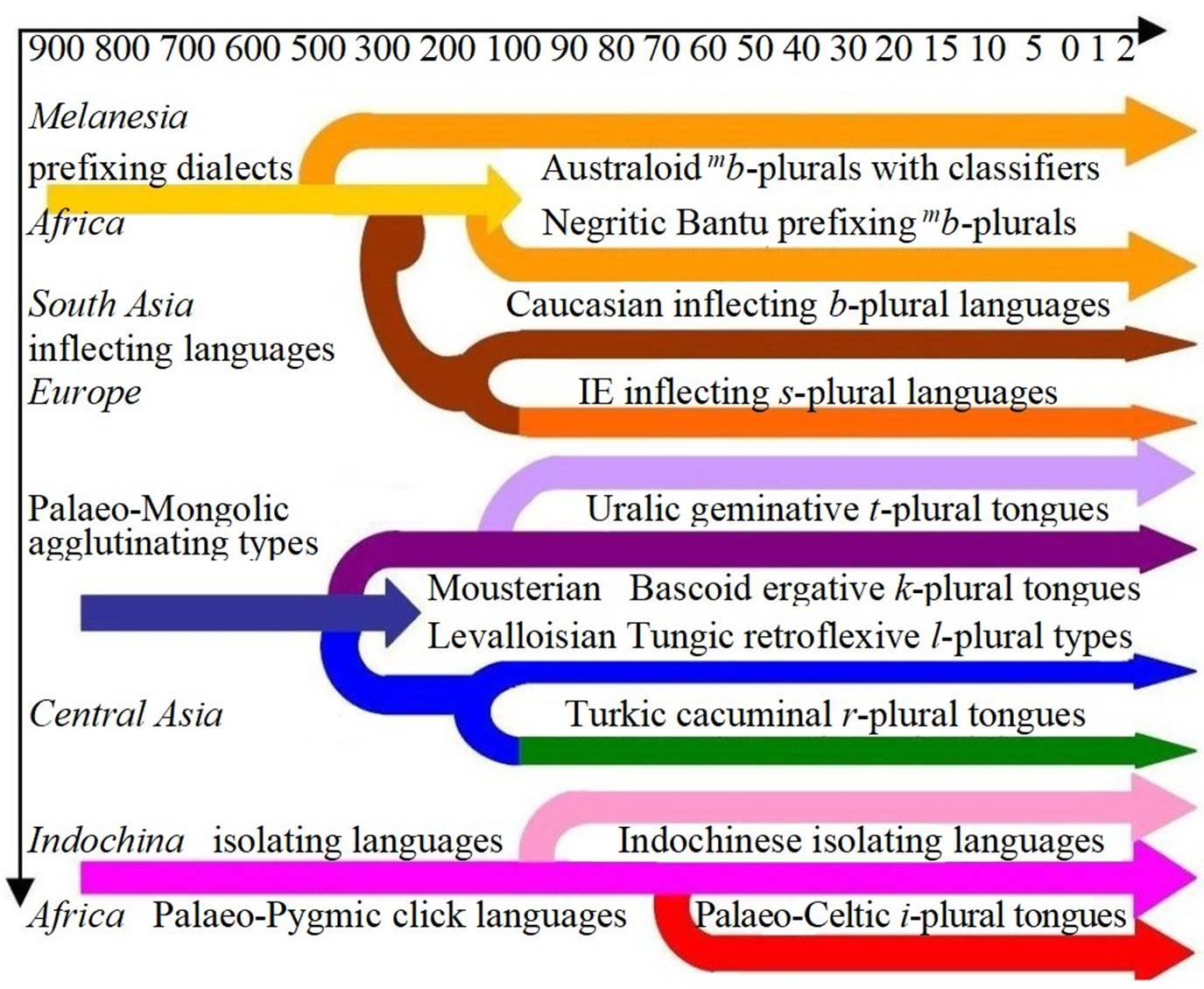

Table 1. The Systematic Glottogenesis of Human Language

Families |

|

Table 2. The Spread of Basco-Abkhaz-Scandian Tribes and Cultures

in Europe |

|

|

Table 3. The Ancient Roman Distribution of Scythic tribes

along the Palaeolithic Mousterian sites (in dotted areas)

The Origins of Palaeolithic Gracile Neanderthalers The bearers of the Mousterian culture are

identified unambiguously with the classic Neanderthals called Homo sapiens neanderthalensis.

Since their first skulls were excavated in

Traditional approaches insist on the dogma of unilinear

sapientisation and concentrate on Homo sapiens sapiens from The primary goal of palaeoanthropology

is not to deal with recent hybridisation but to explain the prehistoric

evolution from primary pure races. Its focus should be on a contrastive

analysis distinguishing human races corresponding to the bearers of

Mousterian, Levalloisian and Micoquian cultures.

The first preliminary step taken usually distinguishes the Levalloisians as the Progressive or Early

Neanderthals from Mousterians as Classic

or Late Neanderthals.1

The second necessary step presupposes distinguishing various generations of

Mousterian colonists into four temporal horizons: Neanderthal A Levalloisians:

Homo sapiens aniensis (Sergii

1935) Neanderthal B

Mousterians: Homo s. neanderthalensis (King 1864) Neanderthal I Clactonians: Swanscombe man, Choukoutien man Homo steinheimensis (Berckhemer 1935) Neanderthal II Tayacians: Fontéchevade man, Ehringsdorf man Neanderthal III Mousterians: La Chapelle aux Saints,

Le Moustier Neanderthal IV

Solutreans:

Solutré skeletons.

The comparative analysis of Neanderthals must count with general tendency

to brachycephalisation that is due to mixing with Lapponoid races remarkable for prominent brachycephaly. The Mongoloids are generally believed to

exhibit higher brachycephaly than most Negroid

races but their skull indices range from mesocephaly

typical of Tungids to moderate brachycephaly

common to the Armenoid Mongolids

with aquiline noses. Accordingly, the Mousterian skull indices rank higher

than those of most Magdalenian and Aurignacian

finds: In order to avoid confusion, we should

give up labelling Neanderthals as various genera and species (Sinanthropus, Homo

neanderthalensis) of extinct primates and treat

them as racial varieties of man apt of mutual interbreeding. Inconvenient

terms of palaeoanthropology should be dropped and

replaced by those of archaeology (Mousterians, Solutreans) so as to unify their taxonomy. The Neanderthal skulls differ from Palaeo-Negroid finds clearly in low foreheads and long

faces. The Rhodesian man from

Broken Hill and Saldanha had a high face, strong

eyebrow arcs and receding chins and mandibles. The Neanderthal man from

Broken Hill was originally dated to 100,000 BP but this dating must be

shifted to a later horizon. The Saldanha man comes

from finds in the Makapansgat cave in Rhodesian

man may be closely related to Steinheim man (from

250,000 to 200,000 BC), who probably imported Mousterian-type Tayacian artifacts to The Steinheim skull was mutilated in the same way as that of

Peking man’s, which may be interpreted as an indirect token of their cannibalist practices. On the other hand, Swanscombe man as a probable protagonist of the Clactonian culture may be linked to the Levalloisian

tradition propagated by a more gracile Homo

sapiens. Their finds are, however, associated with much Acheulean industry due to mixing. The Mousterian

tradition continued later into the Solutrean (from

22,000 to 18,000 BC) and (Extract from P. Bělíček:: The

Synthetic Classification of Human Phenotypes

and Varieties Prague 2018, |

|

The Glottalic

Sound-Repertory of Palaeo-Scythic

Languages The third type of phonology was

attributable to megalith-builders speaking glottalic

languages. Their vocalism and consonantism

consisted from glottalised sounds. Glottalic consonants do not rely on pulmonic

airstream, they are created by the closure of the

glottis that opens a passage from the larynx to the vocal and nasal cavity

(Table 7). Such a system distinguished two types of non-pulmonic

glottalic phonemes, explosive tense ejective

consonants and their lax implosive counterparts. Ejectives are defined as voiceless consonants pronounced with

a glottalic egressive

airstream.1 They are ‘produced with complete glottal closure

and an egressive airstream

following the glottal and oral releases’.2 On the other hand, implosive consonants represent a

group of stops delivered with ‘a mixed glottalic

ingressive and pulmonic egressive airstream

mechanism’.3

These phonemes are very common in languages spoken by tall robust

large-headed brachycephalic mummifiers

and mound-builders.

Table

7. The glottalic and

lingual phonology The Grammatical System of Basco-Scythic Languages

The most important traits of Basco-Scandic

and Ugro-Scythic languages are agglutinating

structures, the category of state and determination with definite and

indefinite articles, distinctive k-plurals

and collective t-plurals, possessive prefixes, OVS word

order, semipredicative constructions with gerunds,

participles and infinitives and alliterative versification. Table 9 demostrates

their grammatical differences form Turanic and Tungusoid langauges.

Table 9. The morphology

of Asiatic races with flake-tool industry The centre point of Asiatic

language families lies in the categories of case, determination, state and

possession. Table 9 proposes a typological classification of

Non-Indo-European language structures that encapsulated from without into

their lexical substance. The left column sums Abkhaz,

Scythoid, Ugroid language

types into the Bascoid family of article-oriented

dialects. Their family is usually counted as a member of the Altaic Sprachbund although it diverges as an independent

subtype. (Extract from P. Bělíček:

The Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, p. 35-42) |