|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

The Upper Palaeolithic Ancestors of Turanic, Turkic and Cimbric Languages Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

||||||||||||||

|

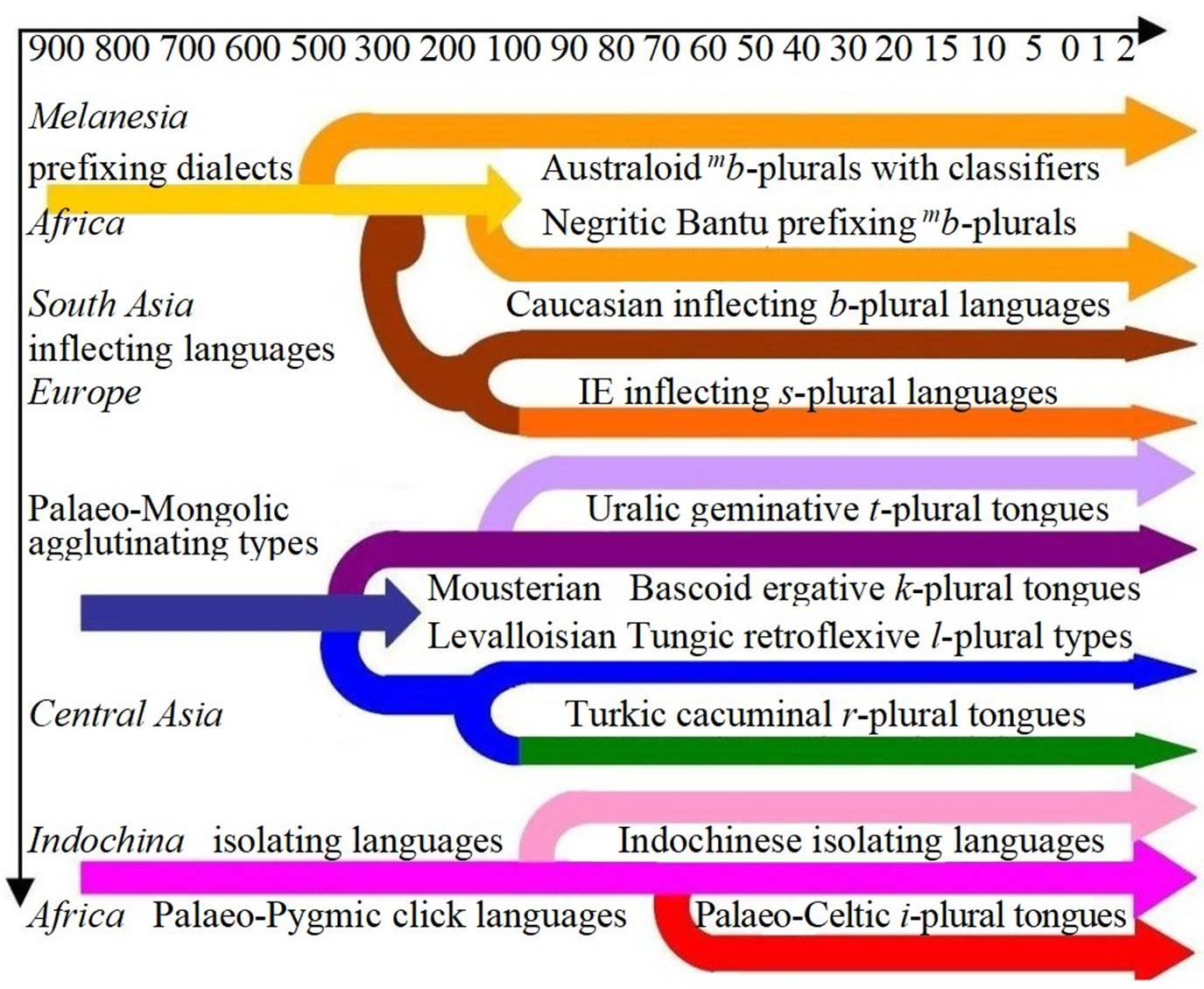

Table 1. The Systematic Glottogenesis of Human

Language Families |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 2. Palaeo-Turanids

(33,000 BC) with microblades, rock shelters, throwing knives and

Y-hg R*-M173 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 2. Renaming

European and Non- European Language Families (from

P. Bělíček: The Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague

2018, Map 5, p. 29) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Origins of Palaeolithic Levalloisian Gracile Neanderthalers The bearers of the Mousterian culture are

identified unambiguously with the classic Neanderthals called Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. Since

their first skulls were excavated in

Traditional approaches insist on the dogma of unilinear

sapientisation and concentrate on Homo sapiens sapiens from The primary goal of palaeoanthropology is

not to deal with recent hybridisation but to explain the prehistoric

evolution from primary pure races. Its focus should be on a contrastive

analysis distinguishing human races corresponding to the bearers of

Mousterian, Levalloisian and Micoquian cultures. The first preliminary step

taken usually distinguishes the Levalloisians as the Progressive or Early

Neanderthals from Mousterians as Classic or Late Neanderthals.1 The second necessary step

presupposes distinguishing various generations of Mousterian colonists into

four temporal horizons: Neanderthal A Levalloisians: Homo sapiens aniensis (Sergii 1935) Neanderthal B

Mousterians: Homo s.

neanderthalensis (King

1864) Neanderthal I Clactonians:

Swanscombe man, Choukoutien man Homo steinheimensis (Berckhemer 1935) Neanderthal II Tayacians:

Fontéchevade man, Ehringsdorf man Neanderthal III Mousterians: La Chapelle aux Saints, Le Moustier Neanderthal IV

Solutreans: Solutré skeletons.

The comparative analysis of Neanderthals must count with general

tendency to brachycephalisation that is due to mixing with Lapponoid races

remarkable for prominent brachycephaly. The Mongoloids are generally believed

to exhibit higher brachycephaly than most Negroid races but their skull

indices range from mesocephaly typical of Tungids to moderate brachycephaly

common to the Armenoid Mongolids with aquiline noses. Accordingly, the

Mousterian skull indices rank higher than those of most Magdalenian and

Aurignacian finds: In order to avoid confusion, we should

give up labelling Neanderthals as various genera and species (Sinanthropus,

Homo neanderthalensis) of extinct

primates and treat them as racial varieties of man apt of mutual

interbreeding. Inconvenient terms of palaeoanthropology should be dropped and

replaced by those of archaeology (Mousterians, Solutreans) so as to unify

their taxonomy. The Neanderthal skulls differ from

Palaeo-Negroid finds clearly in low foreheads and long faces. The Rhodesian man from Broken Hill and

Saldanha had a high face, strong eyebrow arcs and receding chins and

mandibles. The Neanderthal man from Broken Hill was originally dated to

100,000 BP but this dating must be shifted to a later horizon. The Saldanha

man comes from finds in the Makapansgat cave in Rhodesian

man may be closely related to Steinheim man (from 250,000 to 200,000 BC), who

probably imported Mousterian-type Tayacian artifacts to The Pelasgic and

Turanic Retroflexive Consonants The heritage of European Pelasgians is

hidden in clusters of neighbouring languages and may be reconstructed only by

means of indirect parallels. Their racial and lexical component was

significant in Bulgarian, Italian, French and Irish dialects and constituted

the core of the Mediterranean race. The families of Mediterranean

lake-dwellers, Pelasgic seafarers and mythical Hyperboreans in the The families of Pelasgoid, Tungusoid, Turanic and Dravidians

languages descend from the Levalloisian stock of the Early Neanderthalers or

Denisovans, who were piscivorous fishers and lived in waterside

post-dwellings on wooden piers. Their languages were remarkable for the

opposition of aspirated fortis and lenis consonants. Another characteristic

marker were retroflexive stop that often degenerated into consonantal

diphthongs tl, dl, tr, dr. They were preserved

best in the Dravidian languages of The Greek Pelasgians recognised as their

closest relatives Lelegs, Karians, Lydians and Palaites. Their original

language is usually reconstructed from a few rare remains in Greek dialects

such as the lexical suffixes -inthos and -issos, used in hyakinthos

‘hyacinth’ and kyparissos ‘cypress’ (Georgiev 1958; Katićić 1976). The original appearance of Pelasgian

probably resembled Lydian, an Anatolian language with l-plurals and

retroflexed laterals (Shevoroshkin 1967: 24). The Lydians separated as an

independent nation under their ruler Gyges (692-654 BC). Their own

autonym was Maiones written by the ancient Greeks as

Мήονες

(Shevoroshkin 1967: 11). The Iranian family consists of

pastoralists inhabiting dry arid grasslands and it hardly contains any

ancient lake-dwellers except for the Munja and Pashai, whose language uses

the plural ending -ēlā. The Pashai plural marker kuli

is a less reliable trait of Palaeo-Bulgarian ancestry because it appears in

many Indo-Iranian dialects (Yefimov, Edel’man 1978: 277). An Iranian bridge must be presupposed as

a station on the corridor to the Dravidian family. The Dravidian riverside

fishermen and sea peoples consist of the Turcoid group (Malayam, Kannada, Old

Tamil, Kurukh, Kui) with r-plurals and a Tungusoid group (Telugu,

Tulu, New Tamil, Kolami) with l-plurals. The Tulu plural mēji-lu

‘tables’ adds a plural suffix -lu to sg. mēji. The same

plural marker is attached to the Telugu plural gurrā-lu ‘horses.

Modern Tamil uses plurals in -al` where Classic

Tamil applied endings in –ār (Andronov 1962). Gadaba sg. ki – pl.

kil ‘hands’ and Kolami buza-l ‘breasts’ illustrate the plural

suffix -l. Kolami kand-l ‘eyes’ from sg. kan, Naiki kan-l

and Purji kan-ul ‘eyes’ probably indicate a Palaeo-Bulgarian root kan

‘eye’ (Andronov 1978: 350-5). The same group of Dravidian languages tends

to exhibit lambdacism and reproduce z` by l`. While

r-Dravidian languages Kui, Kuvi, Braui, Konda and Gadaba display the

rhotacism z` > r`, Modern Tamil, Tulu, Kolami carry out a

lambdacism z` > l

(Andronov 1978: 340). In r-Dravidian dialect of The opposition of rhotacism and

lambdacism functions as a distinctive trait evident in the ethnonymic pairs Tur-,

Dravid-, Tulu, Telugu. It also helps to distinguish two

branches of Polynesian seafarers. One Turcoid group translated the Altaic god

of heavens Torgut as Tagarro while the other Tungusoid branch called the same

god Tagalo. The Tungusoid branch did not come from Reconstructing residual dialects

presupposes dissecting them from the dominant superstratum according to a few

characteristic residual traits. Pelasgoid and Tungusoid dialects may be

delimited roughly as a group of languages with l-plurals, lambdacism,

alternations d/t/s/r > 1, four laterals with retroflexed

pronunciation, ‘dzekanye’ de > dz and futuropraesentia with

b-markers. Their characteristic sounds are retroflexed laterals dl,

tl pronounced as lateral diphones (consonant affricates) dl,

tl or consonant clusters dl, tl. Their

structure tends to lay the stress on the penultimate and exhibit vertical

vowel harmony. Linguistic comparison must, however, be preceded by reliable

cultural parallels. Reliable typological criteria can be seen in pile-dwellings,

cave burials, menhir tombstones and mollusc necklaces. The anthropological

evidence of Tungids is less conspicuous, it rests on epicanthus,

leptorrhinia, gracile countenance and higher rates of blood groups B. (from P. Bělíček: Prehistoric Dialects, Prague 2004, pp. 559-401) |

|

The

Pulmonic Sound-Repertory of Perigordian, Turanic, Turcoid and Dravidiand Languages On the other hand, Altaic small-game

pastoralists and nomadic fishers created a specific pulmonic phonology

relying on front rounded vowels and the correlation of fortis and lenis

plosives (Table 6). They spoke consonantal pulmonic languages1 produced by the air pressure coming

from the lungs with different degrees of explosive and aspirative force.

According to their tension and explosive charge, their consonants split into

fortis and lenis phonemes. Their vowels distinguished tense and lax

counterparts, too. They were semantically irrelevant as they harmonised the

syllabic relief by vocalic synharmony. Its purpose was to balance series of consonantal

clusters infilled with front or back rounded vowels. Their pronunciation was

often mutated by retroflex colouring. Their stock was divided into Turanids

with apical retroflex rhotacism and Tungids with laminal retroflex rhotacism.

Table

6. The pulmonic phonology of Turcoids and Tungids with

flake-tool industry Elementary grammatical systems fall into three

types of nominal and verbal morphology. The gender-oriented morphology is

attributable to the language family of tall dolichocephals with hand-axe

industry and vegetal subsistence. In its original appearance documented in

African, Melanesian and Australian Negrids it partitioned nouns into classes

of animate, inanimate, vegetal and arboreal classes. These classed were

distinguished by prefixes put in front of nouns. In the Horn of Africa their

family ran upon Asiatic races with agglutinating language structures and

transitioned to suffixing morphology of inflecting type. The group of Asiatic

plant-gatherers, hoe-cultivators and agriculturalists reduced the system of

twelve nominal classifiers to the opposition of animate and inanimate nouns.

Their category included humans, animals, animistic spirits as well as sacral

deities. This

categorisation survived also in Anatolian tongues until their further

expansion in the Balkans encountered Gravettian tribes of Alpinids with

sex-based gender classifications. Their clash resulted in the rise of

sex-based nominal gender enriched by masculine o-stems and feminine a-stems.

The core of European Gothids accepted the dual opposition of masculine and

feminine gender but their core remained reluctant to their addition and

continued to adhere to nominal i-stems. Their subclasses coexisted

with Caucasoid vegetal u/w-stems that can be explained as

remains of Caucasoid b-plurals referring to agricultural crops and

instruments of farming activities. The classification of Indo-European

thematic and athematic stems may be regarded as a hold-over of ancient

invasions and infiltrations surviving in residual form in the territory of The so-called IE t-stems

are reserved for animal species and prevail in terms for pastoralist herding

and animal husbandry. They must have been imported from Uralic languages with

t-plurals by means of Sarmatian raiders and Hallstattian colonists. A

similar account may be given to r-stems that append the marker -r

in Latin sg. genus as opposed to pl. genera. Their origin may

be hypothesised as an import of Mesolithic Turcoid tribes with microlith

flake-tools and r-plural. The occurrence of r-plurals and

umlaut change in German Bach – Bächer, Buch – Bücher is

incorrectly elucidated as a consequence of rhotacism -s > -r

without seeing parallels to Turcoid pluralisation and vowel harmony.

Table 9. The morphology

of Asiatic races with flake-tool industry The centre point of Asiatic

language families lies in the categories of case, determination, state and

possession. Table 9 proposes a typological classification of

Non-Indo-European language structures that encapsulated from without into

their lexical substance. The left column sums Abkhaz, Scythoid, Ugroid

language types into the Bascoid family of article-oriented dialects. Their

family is usually counted as a member of the Altaic Sprachbund

although it diverges as an independent subtype. (from P. Bělíček: The Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague

2018, p. 35-42) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||