The Origins of Palaeolithic

Gracile Neanderthalers

The bearers of the Mousterian culture are

identified unambiguously with the classic Neanderthals called Homo sapiens neanderthalensis.

Since their first skulls were excavated in Gibraltar and at Neanderthal near Düsseldorf in 1856, palaeoanthropologists

have conducted disputes about whether they have survived in modern races or

died out as an extinct offshoot. An

unbiased consideration was harmed by

comparison to more gracile varieties of Homo sapiens sapiens

whose gentler physiognomy doomed

the rugged Neanderthals to extinction. Their low foreheads and prominent

eyebrow ridges fostered erroneous prejudices about their low mental capacity and

made scholars judge them as an extinct regressive side-branch of man. They

tended to emphasise their regressive features, prominent eyebrow arcs, low

foreheads and receding chins but omitted their progressive traits, larger

cranial capacity, stronger arms and great achievements in technology.

Traditional approaches insist on the dogma of unilinear

sapientisation and concentrate on Homo sapiens sapiens from Palestine without noticing his hybrid nature and derived origin. Recent studies

(Day and Stringer 1982) trace his first sapient predecessors back to a single

source, centre and place, to his original seats in east Africa about 120,000

years ago. They count with his early appearance at Omo

I in Ethiopia and Border Cave in Swaziland (from 120,000 to

100,000 BC). They assume that from east Africa he moved to Palestine where his finds

were excavated in Mugharet es-Skhūl

and Jebel Qafzeh (92,000

BC). This cave man showed a prominent chin, a rounded occiput

and a reduced torus supraorbitalis.

He represented Early Moderns followed soon by Late Moderns (Nelson, Jurmain 1988: 558) who invaded Europe between 50,000

and 30,000 BC. This theory is confusing because the Palestinian

settlements correspond to the Natufian culture of Levalloiso-Mousterian stamp and their inhabitants should

be a mixed population of Early and Classic Neanderthals. Their assumed

travels to Europe refer to the colonisation

of Aurignacian cultures of Epi-Levalloisian

descent. It radiated from their Caspian homeland but in Palestine it got an

infusion of Neanderthal blood from surrounding Mousterian populations. Their gracile countenance made anthropologists perceive these

hybrid tribes undeservedly as ‘mythical sapientisators’

of the world.

The primary goal of palaeoanthropology

is not to deal with recent hybridisation but to explain the prehistoric

evolution from primary pure races. Its focus should be on a contrastive

analysis distinguishing human races corresponding to the bearers of

Mousterian, Levalloisian and Micoquian cultures. The

first preliminary step taken usually distinguishes the Levalloisians

as the Progressive or Early Neanderthals from Mousterians as Classic or Late Neanderthals. The second necessary step

presupposes distinguishing various generations of Mousterian colonists into

four temporal horizons:

Neanderthal A Levalloisians:

Homo sapiens aniensis (Sergii

1935)

Neanderthal B

Mousterians: Homo s. neanderthalensis (King 1864)

Neanderthal I Clactonians: Swanscombe man, Choukoutien man

Homo steinheimensis (Berckhemer 1935)

Neanderthal II Tayacians: Fontéchevade man, Ehringsdorf man

Neanderthal III Mousterians: La Chapelle aux Saints,

Le Moustier

Neanderthal IV

Solutreans:

Solutré skeletons.

The comparative analysis of Neanderthals must count with general

tendency to brachycephalisation that is due to mixing with Lapponoid races

remarkable for prominent brachycephaly. The Mongoloids are generally believed

to exhibit higher brachycephaly than most Negroid races but their skull

indices range from mesocephaly typical of Tungids to moderate brachycephaly

common to the Armenoid Mongolids with aquiline noses. Accordingly, the

Mousterian skull indices rank higher than those of most Magdalenian and Aurignacian

finds: Dordogne man 65.7, Brünn 68.2, Cro-Magnon 72.4, Galley Hill

63.4 (G. Schwalbe – E. Fischer; V. P. Alekseyev – I. I. Goxman). We assume that the original average of Mousterian skulls did not

exceed the skull index 77.8 measured in Neanderthals from Teshik-Tash while

Progressive Neanderthals of Levalloisian origin may be calibrated at less

than 72 but owing to the subsequent brachycephalisation they rose to higher

values observed among modern Mongolids and Tungids. A remarkable feature was

their high, angled and prominent nose (M. H. Wolpoff; H. Nelson – R. Jurmain), reminiscent of modern aquiline varieties.

In order to avoid confusion, we should

give up labelling Neanderthals as various genera and species (Sinanthropus, Homo

neanderthalensis) of extinct primates and treat

them as racial varieties of man apt of mutual interbreeding. Inconvenient

terms of palaeoanthropology should be dropped and

replaced by those of archaeology (Mousterians, Solutreans) so as to unify their taxonomy.

The Neanderthal skulls differ from Palaeo-Negroid finds clearly in low foreheads and long

faces. The Rhodesian man from

Broken Hill and Saldanha had a high face, strong

eyebrow arcs and receding chins and mandibles. The Neanderthal man from

Broken Hill was originally dated to 100,000 BP but this dating must be

shifted to a later horizon. The Saldanha man comes

from finds in the Makapansgat cave in Transvaal. An upper jaw of

a 9-year-old Neanderthal baby was excavated at Tanger

in Morocco. A part of a

lower mandible was found at Dire-Dawa in Ethiopia. The modern

Hottentots and Masais display a clearly Mongoloid

type of physiognomy with high cheekbones, long face and even some traces of epicanthus. They fight their foes with leaf-shaped

lances though they abandoned the technique of retouching and make them from

metal now.

Rhodesian

man may be closely related to Steinheim man (from

250,000 to 200,000 BC), who probably imported Mousterian-type Tayacian artifacts to Europe and deserves to be greeted as a forerunner of Mousterian

Neanderthals. The Steinheim skull was

mutilated in the same way as that of Peking man’s, which may be interpreted as an

indirect token of their cannibalist practices. On

the other hand, Swanscombe man as a probable

protagonist of the Clactonian culture may be linked

to the Levalloisian tradition propagated by a more gracile

Homo sapiens. Their finds are, however, associated with much Acheulean industry due to mixing. The Mousterian

tradition continued later into the Solutrean (from

22,000 to 18,000 BC) and Clovis and Folsom leaf-shape cultures (12,000 BC) in America. The only way that allows anthropology to avoid

confusion consists in replacing misleading labels by genetic lineages such as

Mousterian I-V, Levalloisian I-VI.

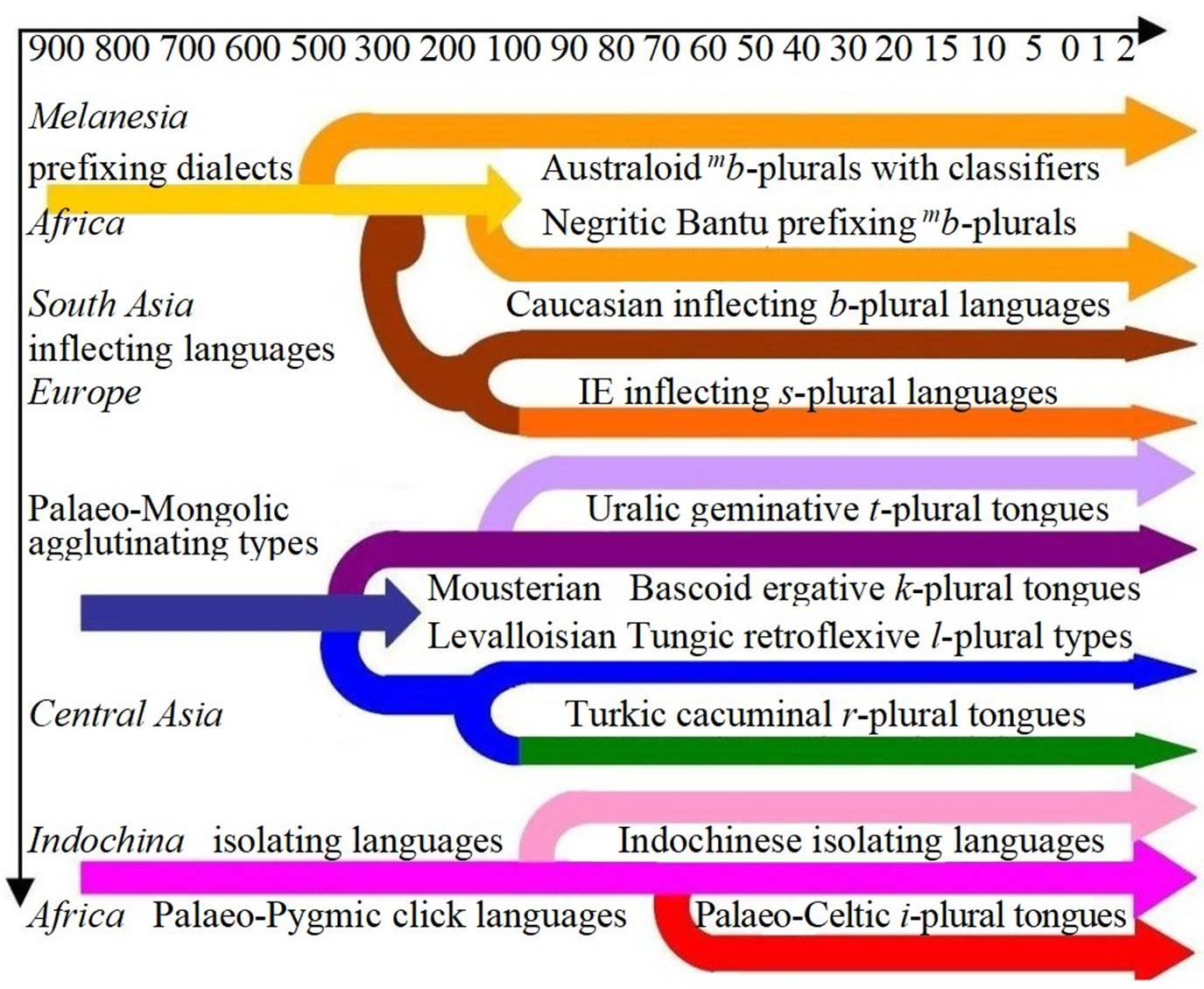

Uralic, Sarmatic and Asiatic Siberian Languages

Uralic languages are generally classified

as members of one Finno-Ugric or Uralo-Ugric Sprachbund. Finns should be excluded from this

unity because their name Finland is derived from Vinnaland ‘land of Wends’ and its

alternative nickname Suomi refers to Saami people. Both designations are applied to short-sized

brachycephalous Lapponoids,

who were incompatible with Siberian tall and robust megafauna-hunters.

Their purebred forefathers were only Siberian mammoth-hunters who sought their

substitutes in the New World. After their extinction they

were compelled to chase the moose and reindeer or adopt their raising and herding.

In the Neolithic they emerged in two independent groups denotable as Estono-Mordvins and Mansi-Ugrians.

The former roved the tundra zone of northern Siberia as the Combed

Ware complex affiliated to the Narva culture (4200 BC) in Estonia. They must have come

into existence as the western offshoot of the Chulmun/Jeulmun

Comb Ware (8000 BC) that won predominance in Korea and Mongolia.

The

common forebear of Estono-Mordvins and Mansi-Ugrians were Palaeo-Siberians

living in the northeast corner of continental Asia. The Palaeo-Siberian languages (Eskimo, Kerek,

Koryak, Chukchee, Nivkh, Kamchadal) look like their

original prototype uniting Mordvin collective t-plurals

and Ugric distinctive k-plurals. Their pair functions as a category of number

also in the tongues of the Khoekhoe cattle-breeders

in the arid areas of Namibia. The earliest appearance

of Ugric languages seems to be conserved marvellously in the Algonquin and

Quechua language family in America. On the

other hand, the majority of Estono-Mordvin tribes remained in the hunting-grounds of

the Siberian tundra and underwent gradual assimilation to Turanic

and Tungusic nations.

The

most impressive trait of Estono-Mordvin tongues remains

hidden in the Uralic agglutinative locative case systems with special morphological

suffixes for essives, illatives,

allatives, elatives and concomitatives.

Their residues were preserved also in the Iranian dialect known as Ossetic. The group of Ossetian,

Yazgulami, Sarikoli, Ishkashmi, Rushani, Vakhi and Yaghnobi languages seems to be associated with Sarmatic horse-breeders in southern Russia. The ancient

Greeks and Romans referred to Uralic tribes as Sauromatae

and nicknamed the Baltic Sea as

Mare Sarmaticum. The central group of Uralic tribes

was concentrated around Merya and Muroma as moose-hunters and hippophagoi

‘horse-eaters’, while their kinsmen settled in the steppe grasslands south of

the Urals as became notable as Sarmatians. They developed

advanced ferrolithic cultures using two-wheeled and

four-wheeled chariots drawn by horses. The admirable mobility of their squads

armed with iron cuirasses, swords and arrows enabled them to conquer large areas

in the Danube Basin as Hallstattian warriors. Their precursors were the Sumerian

donkey-breeders, Amorite horseback riders, Arabic camel-keepers and Tibetan yak-herders.

|

isers

|

The Glottalic Sound-Repertory of Palaeo-Scythic

Languages

The third type of phonology was

attributable to megalith-builders speaking glottalic

languages. Their vocalism and consonantism

consisted from glottalised sounds. Glottalic consonants do not rely on pulmonic

airstream, they are created by the closure of the

glottis that opens a passage from the larynx to the vocal and nasal cavity

(Table 7). Such a system distinguished two types of non-pulmonic

glottalic phonemes, explosive tense ejective

consonants and their lax implosive counterparts. Ejectives are defined as voiceless consonants pronounced with

a glottalic egressive

airstream. They are ‘produced with complete

glottal closure and an egressive airstream following the glottal and oral releases’. On the other hand, implosive consonants represent a group

of stops delivered with ‘a

mixed glottalic ingressive and pulmonic egressive airstream mechanism’. These phonemes

are very common in languages spoken by tall robust large-headed brachycephalic mummifiers and

mound-builders.

|

Glottalic languages

Baskids, Ugrids, Scythids

|

Lappic lingual

phonology

Lappids, Alpinids, Pygmids

|

Sanid lingual phonemes

African

Sanids

|

Murmured

breathy phonemes

Hindus

and Sinids

|

|

reduced

mixed vowel ǝ

reduced

central vowels ǝ ɜ a

|

3-level

or 4-level vocalism:

closed

high, mid, open low

|

reduced

mixed vowel ǝ

vowels: i e a o u

|

short

vowels: i e a o u

long

vowels: ī ā ū

|

|

no

nasal vowels

|

nasal

vowel: ã õ ũ, aⁿ eⁿ uⁿ

|

opposition

of oral

and

nasal vowels

|

nasal vowels: ã ĩ ũ

|

|

advanced

tongue root

harmony

|

no

vowel synharmony

nasal

harmony?

|

no

vowel harmony

nasal

harmony?

|

nasal anusvāra harmonisation

aṁ iṁ uṁ or

ã ĩ ũ

|

|

pharyngeal vowels iˤ eˤ aˤ

oˤ uˤ

|

no

pharyngeal vowels

|

breathy iʱ eʱ aʱ

oʱ uʱ

|

no

pharyngeal vowels

|

|

tense

ejectives: p’ t’ k’

|

palatals:

by dy gy

|

palatals:

by dy gy

|

aspirated

ph dh kh

|

|

lax

implosives: ɓ̥ ɗ̥ ɠ̊

|

sibilant

s-affricates

|

clicks:

ǀ ǁ ǃ ǂ

|

murmured

breathy bh dh gh

|

|

uvular

consonants: q χ

|

no uvulars

|

no uvulars

|

glottal h

|

|

assibilated

affricates sp st sk

|

s-affricates:

ts dz tʃ ʤ

|

ts dz tʃ

|

s-affricates: ʒ dʒ dʒʱ

|

|

velarised aspirates:

pγ tγ kγ

qγ

|

satemised velars

ky: >

s, gy > z

|

velarised aspirates:

pγ tγ kγ

qγ

|

plosives:

p t k b d

murmured

series

|

|

trill

r

|

palatal

fricative ř

|

|

murmured

breathy flap rh

|

|

borrowed tonal systems

|

tone, melody, pitch

|

tone, pitch accent

|

tone, pitch accent

|

Table

7. The glottalic and

lingual phonology

The Grammatical System of Basco-Scythic and Uralo-Sarmatic Languages

|

Article-oriented

nominalisation

Bascoids with articles

and

category

of determination

|

Case-oriented

morphology

Altaic

Turcoids with

agglutinating

language structures

|

Case-oriented

morphology

Siberian

Tungids with

agglutinating

language structures

|

|

suffixing

agglutination

|

suffixing

agglutination

|

suffixing

agglutination

|

|

no

gender categories

|

no

gender categories

|

no

gender categories

|

|

category

of determination

indefinite

and definite articles

|

no

articles

|

no

articles

|

|

ergative

constructions with absolutive, oblique and

ergative case

|

locative

subcategorisation of

cases

into essives and allatives

|

nominative

vs. accusative con-

structions with locative

cases

|

|

plural

and dual number: -k -t

Bascoid: distinctive

k-plurals

Uraloid collective

t-plurals

|

number:

singular –

plural

Turcoid r-plurals

|

number:

singular –

plural

Tungusoid l-plurals

|

|

possession:

possessive prefixes

|

possession:

possessive suffixes

|

possession:

possessive suffixes

|

|

cases:

prefixing case markers

ergative

– absolutive

|

cases:

suffixing case markers

nominative

- accusative

|

cases:

suffixing case markers

nominative

– accusative

|

|

word

order: OVS, SOV

adjective

attributes: NA

nominal

attributes: GN

numeral

attribution: NumN

|

word

order: SOV

adjective

attributes: AN

nominal

attributes: GN

numeral

attribution NumN

|

word

order: SOV

adjective

attributes: AN (NA)

nominal

attributes: GN

numeral

attribution NumN

|

|

adjunctions:

prepositions

conjuctions: prejunctions

|

adjunctions:

postpositions

conjuctions: postjunctions

|

adjunctions:

prepositions,

conjuctions: prejunctions

|

|

analytic semipredication with

gerunds, infinitives

and participles

|

semipredication with gerunds, infinitives and participles

|

analytic semipredication with

gerunds, infinitives and participles

|

|

stress: accent

on initial syllables

|

accent on

ultimate syllables

|

accent on penultimate

syllables

|

|

versification:

alliterative

|

prosody:

rhyming consonance

|

parallelistic

consonance

|

Table 9. The morphology

of Asiatic races with flake-tool industry

The centre point of Asiatic language

families lies in the categories of case, determination, state and possession.

Table 9 proposes a typological classification of Non-Indo-European language

structures that encapsulated from without into their lexical substance. The

left column sums Abkhaz, Scythoid,

Ugroid language types into the Bascoid

family of article-oriented dialects. Their family is usually counted as a

member of the Altaic Sprachbund although it

diverges as an independent subtype.

(from

P. Bělíček: The Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, p.

35-42)

|