|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

The Families of Pelasgic, Tungusic and Uto-Aztecan Languages Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

||||||||||||||

|

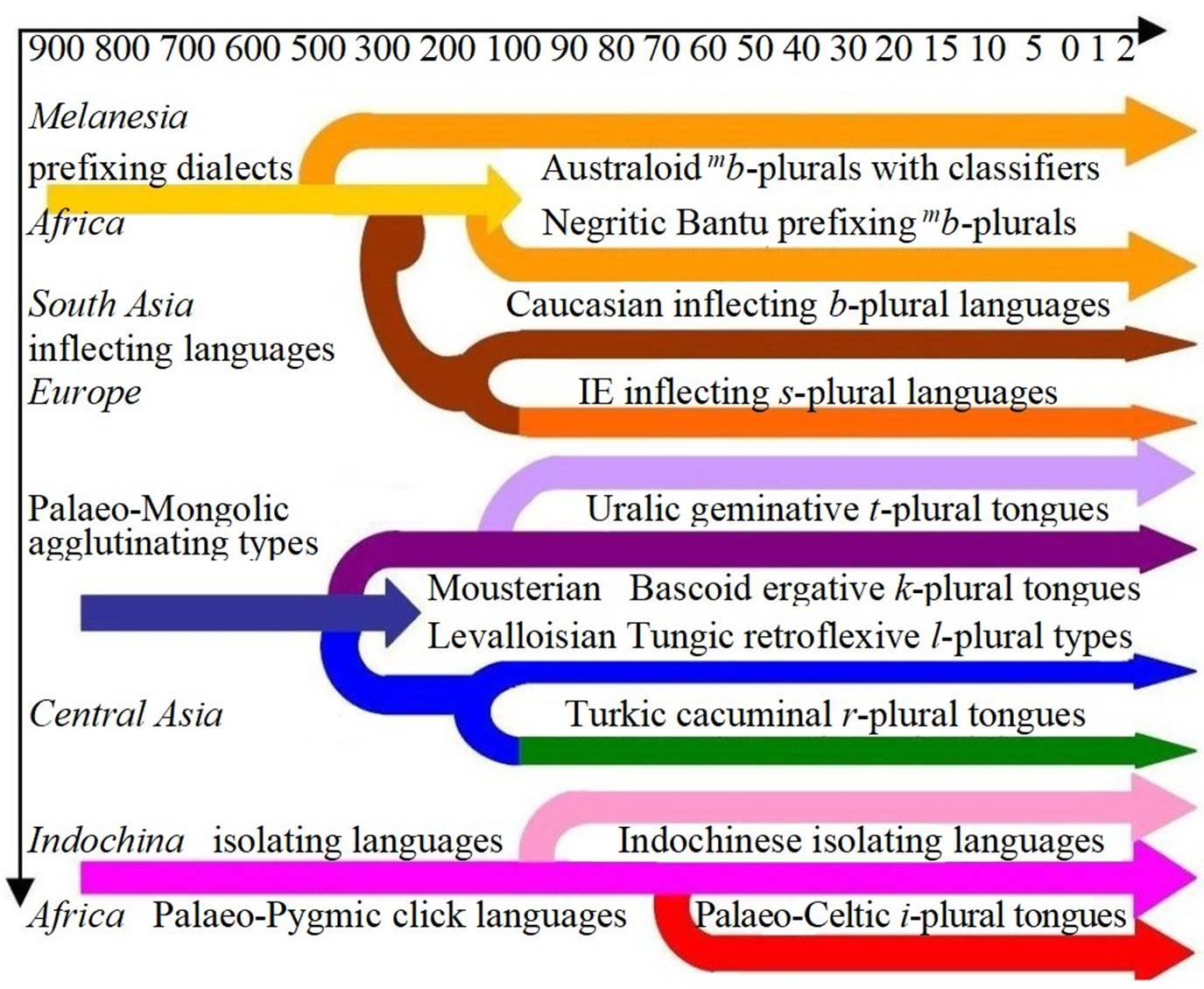

Table 1. The Systematic Glottogenesis of Human Language

Families |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table 2. Aurignacian

Tungids (38,000 BC) with

ochre burials, tepee tents, lake-dwellings, prismatic knives and Y-hg C (from Pavel Bělíček: The Atlas of Systematic

Anthropology I. The Synthetic Classification

of Human Phenotypes and Varieties. Prague 2018, Map 5, pp. 77) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Palaeolithic Origins of Levalloisian Gracile Neanderthalers The bearers of the Mousterian culture are

identified unambiguously with the classic Neanderthals called Homo sapiens neanderthalensis.

Since their first skulls were excavated in

Traditional approaches insist on the dogma of unilinear

sapientisation and concentrate on Homo sapiens sapiens from The primary goal of palaeoanthropology

is not to deal with recent hybridisation but to explain the prehistoric

evolution from primary pure races. Its focus should be on a contrastive

analysis distinguishing human races corresponding to the bearers of

Mousterian, Levalloisian and Micoquian cultures.

The first preliminary step taken usually distinguishes the Levalloisians as the Progressive or Early

Neanderthals from Mousterians as Classic

or Late Neanderthals.1 The

second necessary step presupposes distinguishing various generations of

Mousterian colonists into four temporal horizons: Neanderthal A Levalloisians:

Homo sapiens aniensis (Sergii

1935) Neanderthal B

Mousterians:

Homo s. neanderthalensis (King 1864) Neanderthal I Clactonians: Swanscombe man, Choukoutien man Homo steinheimensis (Berckhemer 1935) Neanderthal II Tayacians: Fontéchevade man, Ehringsdorf man Neanderthal III Mousterians: La Chapelle aux Saints,

Le Moustier Neanderthal IV

Solutreans:

Solutré skeletons.

The comparative analysis of Neanderthals must count with general

tendency to brachycephalisation that is due to mixing with Lapponoid races

remarkable for prominent brachycephaly. The Mongoloids are generally believed

to exhibit higher brachycephaly than most Negroid races but their skull

indices range from mesocephaly typical of Tungids to moderate brachycephaly

common to the Armenoid Mongolids with aquiline noses. Accordingly, the

Mousterian skull indices rank higher than those of most Magdalenian and

Aurignacian finds: In order to avoid confusion, we should

give up labelling Neanderthals as various genera and species (Sinanthropus, Homo

neanderthalensis) of extinct primates and treat

them as racial varieties of man apt of mutual interbreeding. Inconvenient

terms of palaeoanthropology should be dropped and

replaced by those of archaeology (Mousterians, Solutreans) so as to unify their taxonomy. The Neanderthal skulls differ from Palaeo-Negroid finds clearly in low foreheads and long

faces. The Rhodesian man from

Broken Hill and Saldanha had a high face, strong

eyebrow arcs and receding chins and mandibles. The Neanderthal man from

Broken Hill was originally dated to 100,000 BP but this dating must be

shifted to a later horizon. The Saldanha man comes

from finds in the Makapansgat cave in Rhodesian

man may be closely related to Steinheim man (from

250,000 to 200,000 BC), who probably imported Mousterian-type Tayacian artifacts to The Pelasgic and Turanic Retroflexive Consonants The heritage of European Pelasgians is hidden in clusters of neighbouring

languages and may be reconstructed only by means of indirect parallels. Their

racial and lexical component was significant in Bulgarian, Italian, French

and Irish dialects and constituted the core of the Mediterranean race. The

families of Mediterranean lake-dwellers, Pelasgic

seafarers and mythical Hyperboreans in the The families of Pelasgoid, Tungusoid, Turanic and

Dravidians languages descend from the Levalloisian stock of the Early Neanderthalers or Denisovans,

who were piscivorous fishers and lived in waterside

post-dwellings on wooden piers. Their languages were remarkable for the

opposition of aspirated fortis and lenis

consonants. Another characteristic marker were retroflexive

stop that often degenerated into consonantal diphthongs tl,

dl, tr, dr. They were

preserved best in the Dravidian languages of The Greek Pelasgians

recognised as their closest relatives Lelegs, Karians, Lydians and Palaites. Their original language is usually

reconstructed from a few rare remains in Greek dialects such as the lexical

suffixes -inthos and -issos,

used in hyakinthos ‘hyacinth’ and kyparissos ‘cypress’ (Georgiev

1958; Katićić 1976). The original

appearance of Pelasgian probably resembled Lydian,

an Anatolian language with l-plurals and retroflexed laterals (Shevoroshkin 1967: 24). The Lydians

separated as an independent nation under their ruler Gyges

(692-654 BC). Their own autonym was Maiones

written by the ancient Greeks as Мήονες (Shevoroshkin

1967: 11). The Iranian family consists of pastoralists inhabiting dry arid grasslands and it hardly

contains any ancient lake-dwellers except for the Munja

and Pashai, whose language uses the plural ending -ēlā. The Pashai

plural marker kuli is a less reliable trait

of Palaeo-Bulgarian ancestry because it appears in

many Indo-Iranian dialects (Yefimov, Edel’man 1978: 277).

An Iranian bridge must be presupposed as

a station on the corridor to the Dravidian family. The Dravidian riverside

fishermen and sea peoples consist of the Turcoid

group (Malayam, Kannada, Old Tamil, Kurukh, Kui) with r-plurals

and a Tungusoid group (Telugu, Tulu,

New Tamil, Kolami) with l-plurals. The Tulu plural mēji-lu

‘tables’ adds a plural suffix -lu to sg. mēji. The same

plural marker is attached to the Telugu plural gurrā-lu

‘horses. Modern Tamil uses plurals in -al` where Classic

Tamil applied endings in –ār (Andronov 1962). Gadaba sg. ki – pl. kil ‘hands’ and Kolami buza-l ‘breasts’ illustrate the plural suffix -l.

Kolami kand-l

‘eyes’ from sg. kan,

Naiki kan-l

and Purji kan-ul

‘eyes’ probably indicate a Palaeo-Bulgarian

root kan ‘eye’ (Andronov

1978: 350-5). The same group of Dravidian languages tends to exhibit lambdacism and reproduce z` by l`. While

r-Dravidian languages Kui, Kuvi,

Braui, Konda and Gadaba display the rhotacism z` > r`, Modern Tamil, Tulu,

Kolami carry out a lambdacism

z` > l (Andronov 1978: 340). In r-Dravidian dialect of The opposition of rhotacism

and lambdacism functions as a distinctive trait

evident in the ethnonymic pairs Tur-,

Dravid-, Tulu,

Telugu. It also helps to distinguish two branches of Polynesian

seafarers. One Turcoid group translated the Altaic god

of heavens Torgut as Tagarro

while the other Tungusoid branch called the same

god Tagalo. The Tungusoid

branch did not come from Reconstructing

residual dialects presupposes dissecting them from the

dominant superstratum according

to a few characteristic residual traits. Pelasgoid and Tungusoid dialects may be delimited

roughly as a group of languages with l-plurals, lambdacism, alternations d/t/s/r

> 1, four laterals

with retroflexed pronunciation, ‘dzekanye’

de > dz and futuropraesentia with b-markers. Their characteristic sounds are retroflexed laterals dl, tl pronounced

as lateral diphones (consonant affricates) dl, tl

or consonant clusters dl, tl. Their structure tends to lay the stress on the penultimate and exhibit vertical vowel harmony. Linguistic comparison must, however, be preceded by reliable cultural parallels. Reliable typological criteria can be seen

in pile-dwellings, cave burials, menhir tombstones and mollusc necklaces. The anthropological evidence of Tungids is

less conspicuous, it rests on epicanthus,

leptorrhinia, gracile countenance and higher rates of blood groups

B. (from

P. Bělíček: Prehistoric Dialects, Prague 2004, pp. 559-401) |

|

The Pulmonic Sound-Repertory of Levalloisian, Pelasgic and Tungusic

Languages On the other hand, Altaic small-game pastoralists and nomadic fishers created a specific pulmonic phonology relying on front rounded vowels and

the correlation of fortis and lenis plosives (Table

6). They spoke consonantal pulmonic

languages1 produced by the air

pressure coming from the lungs with different degrees of explosive and aspirative force. According to their tension and

explosive charge, their consonants split into fortis

and lenis phonemes. Their vowels distinguished tense and lax counterparts,

too. They were semantically irrelevant as they harmonised the syllabic relief

by vocalic synharmony. Its purpose was to balance

series of consonantal clusters infilled with front

or back rounded vowels. Their pronunciation was often mutated by retroflex

colouring. Their stock was divided into Turanids

with apical retroflex rhotacism and Tungids with laminal retroflex rhotacism.

Table

6. The pulmonic

phonology of Turcoids and Tungids

with flake-tool industry Elementary grammatical

systems fall into three types of nominal and verbal morphology. The

gender-oriented morphology is attributable to the language family of tall dolichocephals with hand-axe industry and vegetal

subsistence. In its original appearance documented in African, Melanesian and

Australian Negrids it partitioned nouns into

classes of animate, inanimate, vegetal and arboreal classes. These classed

were distinguished by prefixes put in front of nouns. In the Horn of Africa

their family ran upon Asiatic races with agglutinating language structures

and transitioned to suffixing morphology of inflecting type. The group of

Asiatic plant-gatherers, hoe-cultivators and agriculturalists reduced the

system of twelve nominal classifiers to the opposition of animate and

inanimate nouns. Their category included humans, animals, animistic spirits

as well as sacral deities. This categorisation survived also in Anatolian tongues until their

further expansion in the Balkans encountered Gravettian

tribes of Alpinids with sex-based gender

classifications. Their clash resulted in the rise of sex-based nominal gender

enriched by masculine o-stems and feminine a-stems. The core of

European Gothids accepted the dual opposition of

masculine and feminine gender but their core remained reluctant to their

addition and continued to adhere to nominal i-stems.

Their subclasses coexisted with Caucasoid vegetal u/w-stems

that can be explained as remains of Caucasoid b-plurals referring to

agricultural crops and instruments of farming activities. The classification

of Indo-European thematic and athematic stems may

be regarded as a hold-over of ancient invasions and infiltrations surviving

in residual form in the territory of The so-called IE t-stems are

reserved for animal species and prevail in terms for pastoralist

herding and animal husbandry. They must have been imported from Uralic

languages with t-plurals by means of Sarmatian

raiders and Hallstattian colonists. A similar

account may be given to r-stems that append the marker -r in

Latin sg. genus as opposed to pl. genera.

Their origin may be hypothesised as an import of Mesolithic Turcoid tribes with microlith

flake-tools and r-plural. The occurrence of r-plurals and

umlaut change in German Bach – Bächer, Buch – Bücher is

incorrectly elucidated as a consequence of rhotacism

-s > -r without seeing parallels to Turcoid

pluralisation and vowel harmony.

Table 9. The morphology

of Asiatic races with flake-tool industry The centre point of Asiatic

language families lies in the categories of case, determination, state and possession.

Table 9 proposes a typological classification of Non-Indo-European language

structures that encapsulated from without into their lexical substance. The

left column sums Abkhaz, Scythoid,

Ugroid language types into the Bascoid

family of article-oriented dialects. Their family is usually counted as a

member of the Altaic Sprachbund although it

diverges as an independent subtype. (from

P. Bělíček: The Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, p.

35-42) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||