|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

The Racial and Linguistic Groups of Negrids,

Bantuids, Melanids and Amazonides Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

||||||||||||||

|

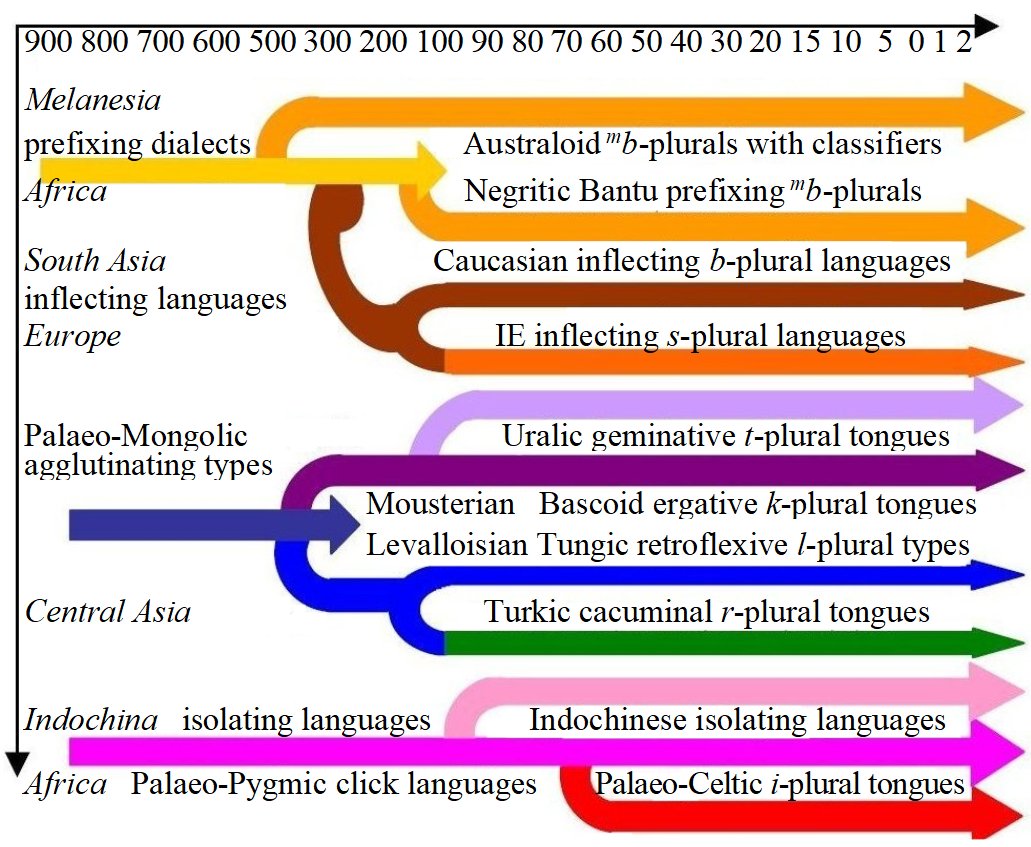

Table 1. The Systematic Glottogenesis of Human Language

Families |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Map 1. The Migration Routes of Bantu Negrids to Papua, Melanesia and Amazonia |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Oldowan Colonisation

Traditional anthropology operates with

theoretical models of the triumphal spread of Homo sapiens and his

out-of-Africa propagation.1 It is

based on a pliable all-explaining construction that unfortunately lacks

unequivocal support in archaeological evidence. Its argumentation buries Homo

erectus as an extinct species and replaces his reign by a gracile successor inhabiting lakeside districts of the

East African Depression. These territories were formerly occupied by his

rival Homo rudolfensis indulging in

waterside ecosystems. His life-style was probably inherited by the race of

East African Kafrids producing Levalloisian

flake-tools. About 500,000 and 125,000 BP they set out on several migrations

heading for There exists a grave suspicion that their

gentle traits misled anthropologists into considering them as the sole

forefathers of all human races. They did not realise that Classic comparative linguistics

presupposes more conservative dating, the founder of Bantu philological

studies Harry H. Johnston advanced much later estimates of Bantu origins. He

presupposed that obvious analogies between African Bantu tongues and

Australian Aboriginal had been due to contacts dated to a few centuries AD.2 Anthropologists attempted to solve

this crux by searching for the earliest African digs and fossils. For a long

time they recognised the earliest ancestor of black Bantu people in the

African fossils of Asselar man. His remains were

found near The issue of common ancestry linking

African, Melanesian and Australian black people into one anthropological

group is still open to dispute. The prevailing opinion regards their racial

groups as independent outgrowths of Homo sapiens that developed on

different continents by adapting to similar tropical climate. Our opinion

proclaims that they represent the progeny of the earliest Oldowan

colonists. The

chief objections to the concept of Palaeo-Negrid

unity emphasise great differences in hair. The hair of Melanesians is wavy or

straight owing to contacts with neighbouring Polynesians. The hair of Australids is as wavy, silky and kinky as

that of Veddoids. The original racial archetype is preserved only in

African Negrids, whose hair is woolly, frizzly and curly. Racial differences among black melanodermic and ulotrichous

types are mostly due to secondary influences but they also disclose common

archaic traits receding in African archetypes. For instance, Australids differ from African Negrids

by higher occurrence of the so-called ‘sagittal

keel’. Originally, it was typical of Homo erectus as a survival of crista sagittalis

in Paranthropus boisei.

Other archaic features of Australids include also

greater prognathism and large heavy jaws betraying

vegetal subsistence. Such findings do not contradict common origin but

confirm the original unity by preserving the more archaic status. They prove

that the original lineage of robust herbivores may have survived better in

remote isolates. The progeny of Homo erectus and Oldowan wanderers appeared also in Amazonian peasants

pertaining to the Tupí-Guraní language family.

Their burial customs prescribe excarnations of the

dead grandfathers’ skulls and skeletons. Formerly, their tribes practiced

ritual cannibalistic endophagy, their

survivors originally ate their flesh and drank their blood in hope they would

take over their magic spiritual powers. Their recent progeny replaced these

barbarous ceremonies by consuming them in burnt ashes baked in cakes or

blended in drinks. The Bantu tribe Geshu boil their dead by night, cut off pieces of the

flesh, divide them among women and leave the rest to the jackals.1 This happens also in the The Amazonian connection of Palaeo-Negrids is scented also by geneticists.4 An important

observation was made by Christy Turners,5 who studied dolichocephalous crania of Amazonian

tribes in The undoubtable

existence of prehistoric Palaeo-Negritic unity

pulls down all the walls of traditional prehistoric studies. The American

linguist Johanna Nichols applied statistical methods to prove that vocal languages

started diversifying in human species at least 100,000 years ago.8 Comparisons of Bantu, Australian,

Melanesian and Amazonian languages bring evidence of many structural

analogies. They show that it is difficult to find common lexical roots in

their word stock, but there exist conspicuous parallels in categories of

phonology and grammar. These languages include initial prenasalised

stops

There exist grave reasons for acknowledging four principal palaeo-races that stood at the cradle of humankind and

arose by adapting to the basic ecotypes in (i) the herbivorous

plant-gatherer Homo erectus remarkable for the Oldowan

culture (Y-hg E), who may have become the progenitor of the equatorial race

of Negrids, (ii) the carnivorous

hunter Laetoli man noted for volcano burials

and the beehive-dwelling culture of Eickstedt’s Khoids with the haplotype

Y-hg B, (iii) the piscivorous fisher Homo rudolfensis

with the Y-hg B, who developed the Levalloisian culture (500,000 BP) and gave

birth to the race of lake-dwelling Kafrids in the

East African Depression, (iv) the omnivorous

and insectivorous race of Eickstedt’s Sanids affiliated with the Negrillo

and Lappids. These

lineages ascertain the genetic continuity of certain ecotypes and modes of

subsistence between hominids, hominins and human

races. They may have been responsible for the origin of several survivors

differentiated into robust plant-eaters (Negrids),

dwarfish omnivores and insectivores (Sanids), lacustrine fish-eaters (Tungusoid

Kafrids and the carnivorous hunters (Coon’s Capoid race, Biasutti’s

Steatopygids9, Eickstedt’s

Khoids). The Analytic Decomposition of Cordal

Axe-Tool Languages

It is

erroneous to identify the birth of Indo-European with Old Indian and imagine

its glottogenesis as a series of sound shifts

transforming Vedic Sanskrit phonemes. Jacob Grimm’s laws overestimated

Sanskrit as direct evidence of the early state of Indo-European and traced

its development as a westward move from

Table 10. Conservative embeddings and

regressive intrusions in Old Indian consonantism The first autochthons in The first Indo-European

newcomers were Campignian Littoralists

(10,000 BC) with cordmarked pottery, who colonized

the The Dravidian element in Old

Indian was represented by retroflex consonants written as ṭ, ḍ, ṇ,

ṣ, ẓ, ḷ, ɾ̣, ɹ̣

but the IPA standard records them as /ʈ, ɖ ,

ɳ, ʂ, ʐ, ɭ, ɻ, ɽ/. They were notable

for pronunciation with the tip of the tongue bent backwards in a concave or curled shape. Their use was obliterated in

most language families but their remains often survive in the affricates tr- dr-, tl- and dl-. Most types of notation

do not distinguish their apical and laminal

pronunciation. The laminal retroflex consonants

were characteristic of Tungusoid fishermen, who

disseminated them in One of typical Indo-European consonantal

clusters is seen in clusters combining sibilants with plosives and sonants. Their majority was formed by the concatenations sp-, st-, sk with presibilised surd plosives and the groups sn-, sl-, sr- formed by presibilised surd sonants. The fact that they were derived

from surd sonants betrays their non-Indo-European

origin because the native IE sonants were voiced. The residues of presibilised clusters appeared also in Georgian and

Caucasian languages, which suggested a false impression of their close

genetic affinity. In fact, they arose as an Europeanisation

of Altaic roots with fortis and glottalic

stops. Their original fortis pronunciation was

perceived as monophonematic aspirated stops

ph- and hp- or a pair of two

phonemes ph- or hp-. A similar process of deaspiration took place

in Czech chvíle ‘while’ derived from Old High German hwila and New German Weile.

Such assibilation was common especially in assimilating the glottalic ejectives of Scythoid kurgan-builders and Khoisan

herders with copular beehive dwellings and leaf-shaped lance-heads. The South

African Khoekhoe tribes belonged to the group of pastoralists such as the Maasai,

Musgu, Berber Imazhigen

and Iberian Basques, whose ethnonyms resonate also

in the place names Altaic intrusions into Indo-European encompassed also retroflex plosives that are usually transcribed in India as /ṭ, ḍ, ṇ, ṣ, ẓ, ḷ, ɾ̣, ɹ/̣ but in the IPA notation they are rendered as /ʈ, ɖ , ɳ, ʂ, ʐ, ɭ, ɻ, ɽ/. These sounds come from Turcoid and Tungusoid languages and often underwent dephonologisation into r-affricates or l-affricates. Such assimilative decomposition led to r-affricative biphonemes /pr, tr, dr, kr, mr, nr/, or l-affricates /pl, tl, dl, kl, ml, nl/. The final stage of dephonologisation turned fortis voiceless consonants sounds into presibilated consonantal clusters. Fortis retroflexed cacuminals were decomposed into cacuminal clusters /spr- str- skr-/, while fortis retroflexed laminals degenerated into laminal clusters /spl- stl- skl/. Almost all reconstructions

of Indo-European count with a special series of palatals /*k', *g', *g'ʰ/ transcribed also as /*ky, *gy*,

gyʰ/. Indian palatal phonemes have

to be classified as an import of the short-sized Negritos,

Alpinids and Lappids, who

detested velar and guttural consonants and removed them by satemisation. The first wave of Negritos

arrived in The Scythoid

element was present in |

The Palaeo-Negric, Palaeo-Hmongic, Palaeo-Melanese and Palaeo-Amazonian

Phonology There

were several principal turnabouts in the tongues of robust dolichocephalous

axe-tool makers. They were all herbivorous plant-gatherers and seed-eaters,

who dug up their crops with pebble-stone-choppers and hand-axes. Their

eastern migrations headed for the The

original speech patterns of the black Negrids and Melanids were preserved best in Bantu languages. When the ancient Oldowans

moved to In The problem of Acheulean,

Caucasian and Indo-European continuity is solved by focusing on avalanches of

ephemeral sound shifts instead of considering genetic stability and

structural typology. The white Europoid race is an

outgrowth of macrolithic hand-axe populations of

tall dolichocephals with vegetal subsistence and

(pre)agricultural dispositions, and its development competed with the Altaic

races with flake-tool cultures. These cultural traditions did not differentiate

by unilinear monogenesis from a common prehistoric

unity but pursued independent growth by paragenesis

in several interfertile and interbreedable

racial lineages. Their archetypal differences were manifested by absolutely

incompatible phonologies and grammatical systems. African Negrids,

Asiatic Caucasoids and European Nordids

applied cordal languages, whose consonantism was based on the vibration of vocal cords

and the opposition of voiced and surd phonemes (Table 5). They pronounced

vocalic cordal phonemes based on open syllables and

phonemes produced by airstream passing through

vibrating vocal cords. If there were any structural changes, they were caused

by mixing with Altaic agglutinating systems.

Table 5. The cordal

phonology of dolichocephals with macrolithic hand-axe industry The Situation of Indo-European

among Grammatical Systems

Classical historical grammar fulminated

thousands of sound shifts but brought few testimonies of similar radical

changes in grammar, accidence and syntax. Phonological repertories tend to

exhibit radical innovations but they remain unparalleled in other linguistic

aspects. In cultural evolution most grammatical categories remain relatively

untouched and adopt mutations only in suffixal

morphemes. This discrepancy is removed if linguistic analysis focuses on

spoken dialects instead of the official written standard of national

languages. This is another good reason for promoting linguistic typological

studies that do not restrict their focus to describing individual language

structures but build bridges between tongues with similar types of traits.

Table 8.

The nominal morphology of dolichocephals

with macrolithic hand-axe industry Elementary grammatical systems fall into

three types of nominal and verbal morphology. The gender-oriented morphology

is attributable to the language family of tall dolichocephals

with hand-axe industry and vegetal subsistence. In its original appearance documented

in African, Melanesian and Australian Negrids it

partitioned nouns into classes of animate, inanimate, vegetal and arboreal

classes. These classed were distinguished by prefixes put in front of nouns.

In the Horn of Africa their family ran upon Asiatic races with agglutinating

language structures and transitioned to suffixing morphology of inflecting

type. The group of Asiatic plant-gatherers, hoe-cultivators and

agriculturalists reduced the system of twelve nominal classifiers to the

opposition of animate and inanimate nouns. Their category included humans,

animals, animistic spirits as well as sacral deities. This

categorisation survived also in Anatolian tongues until their further

expansion in the Balkans encountered Gravettian

tribes of Alpinids with sex-based gender

classifications. Their clash resulted in the rise of sex-based nominal gender

enriched by masculine o-stems and feminine a-stems. The core of

European Gothids accepted the dual opposition of

masculine and feminine gender but their core remained reluctant to their

addition and continued to adhere to nominal i-stems.

Their subclasses coexisted with Caucasoid vegetal u/w-stems

that can be explained as remains of Caucasoid b-plurals referring to

agricultural crops and instruments of farming activities. The classification

of Indo-European thematic and athematic stems may

be regarded as a hold-over of ancient invasions and infiltrations surviving

in residual form in the territory of (from

P. Bělíček: The Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, p.

35-42) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||