|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

The Families of Lappic, Slavic, Gallic, Annamitic and Sinic Languages Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

||||||||||||||

|

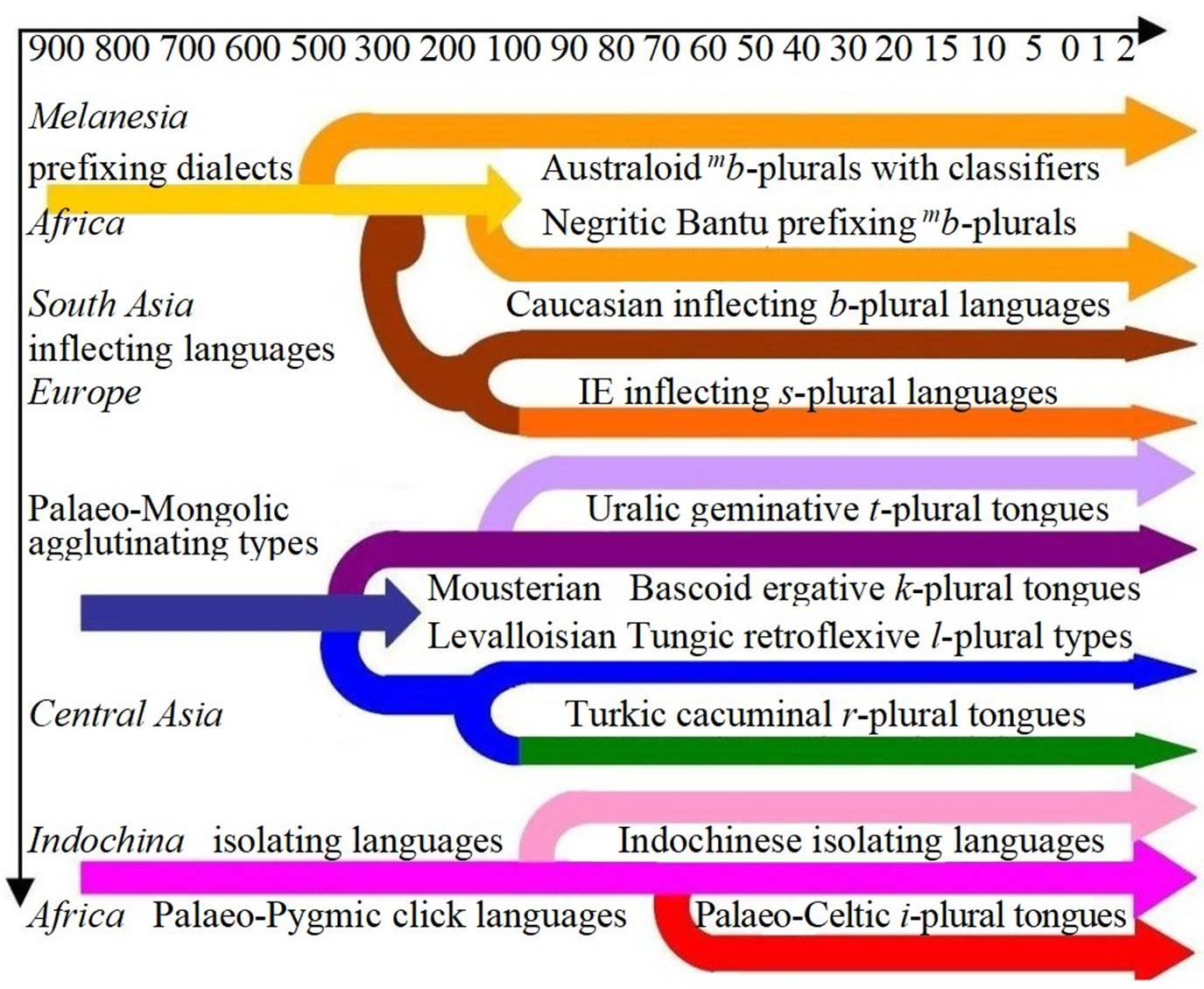

Table 1. The Systematic Glottogenesis of Human Language

Families |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Map 1. Lappids with incineration burials, semisubterranean lean-to huts, blood group A, Y-hg C and O, lingual phonology and isolating reduplicative morphology (from Pavel Bělíček: The Atlas of Systematic

Anthropology I. The Synthetic Classification

of Human Phenotypes and Varieties. Prague 2018, Map 5, pp. 77) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Map 1. Indices of shortsized stature in Lappids (after R. Biasutti) (Pavel Bělíček: The Synthetic Classification of Human Phenotypes and Varieties. Prague 2018, p. 97, Map 12) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Map 2. The distribution and ethnic identification of high rates of the blood group A |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Clicks, Implosives, Palatals and their Satemism

Clicks. The Bushmen are mixed

racially with the Hottentot cattle-breeders but

their anthropology and language structures preserve many archaic features of

the Palaeo-Pygmic race. Most of their words exhibit

bisyllabic patterns and almost 70 per cent of their

lexical roots start with clicks. Clicks are defined as ‘velar injectives whose pronunciation accompanies a velar

occlusion with a labial, dental, alveolar, lateral or palatal occlusion’ (Krupa, Genzor, Drozdík 1983: 409). They are called injectives

or implosives because they are pronounced with an inspiratory

stream of air that is common in clicking the tongue and sucking liquid food.

The current linguistic tradition has introduced specific symbols for their

notation but it is preferable to replace them by a system of diacritic

writing so as to emphasise their analogy with palatals. Satemism. The systemic shortage of backer stops

resulted in satemism, a tendency to

reproduce velars in loanwords as sibilant or affricates. Comparative

linguistics classifies descendants of the eastern branch of Indo-European as satm languages

because they carried out the change k’e

> s seen in the Avesta satm ‘hundred’. On

the other hand, descendants of the western branch of Indo-European are

classified as centum languages after Latin centum ‘hundred’ in

belief that they depalatalised palatal stops by

shifts k’ > k and g’ > g. We believe that the dichotomy

of centum and sat ǝm languages cannot be reduced to an isolated shift in

the evolution of Indo-European but represents a more general tendency to

avoiding velar consonants. A broader view would explain it as satemism, a series of shifts reproducing velars

before front vowels e, i as

sibilants, common to all Pygmoid and Laponoid languages. Indo-European comparative

grammar assumes that the sat ǝm shift k’e > s occurred when the Indo-Iranians and

Slavs began to split from other Indo-Europeans. This shift assibilated

Indo-European palatal velars k’, g’, g’h:

Table 148. Assibilation

in eastern Indo-European languages (Erhart

1982: 51) After separating into families, this assibilation was followed by

several independent palatalisations. Indo-Iranian ke, kwe,

ki, kwi

changed into ča, či,

ge, gwe,

gi, gwi

into ja, ji

and ghe, gwhe,

ghi, gwhi

into ha, hi. Similar pala-talisations

took place in Common Slavic, Old French, Latvian and Tokharian.

The first palatalisation in Common Slavic carried

out the shifts k > č and g > ž. The second Slavic palatalisation in the late 1st millennium AD

turned kě, ki

into cě, ci,

gě, gi into

zě, zi and chě, chi into sě,

si (Erhart 1982: 51).

Melodic Prosody and Palatal Vocalism

Tones. The original system of melodic tonality was

preserved in most languages of Laponoid origin as a

complementary phenomenon without phonemic relevance. In the Indo-European

area melodic accent of acute and circumflex type can be observed in Slavonic,

Baltic, Greek and Indo-Iranian languages. It usually appears only in the

first or second part of two-mora syllables and

exhibits a rising or falling intonation according as the first or the second mora is accented. The acute in Greek and Serbo-Croatian

has a rising intonation with an accent laid on the second mora.

The circumflex has a falling intonation with the accent placed on the first mora. J. Kuryłowicz (1952,

1968) studied their rules in comparison to Lithuanian and concluded that

their tones are of different origin. The Lithuanian circumflex carries a

rising tone while the acute a falling tone (Erhart

1982: 63). The Indo-Iranian melodic accent was

evidenced in Vedic texts but its modern survivals are confined to Panjabi, Rajastani, Paxari and Hindi. Panjabi has a low (or falling-rising) tone, middle tone

and high tone (rising or rising-falling). These tones exhibit phonemic

relevance because they distinguish the meaning in similar words ghoŗā /kòŗa/

‘horse’, kohŗā /kōŗa/

‘whip’, koŗā /kóŗa/

‘прокаженный’ (Zograf 1976:

180-1). Nasal vowels. Laponoid

tribes had vowel and consonant systems that were based on palatal and nasal

correlations. Nasal vowels ĩ,

ã, ũ do not regularly

appear in languages with prenasalised stops but

both may have a common origin in dissociated nasals. The Old Slavonic nasals ę, ą are explained either

as ‘nasal diphthongs’ eN, oN where the nasal

quality is concentrated in an independent nasal semivowel N (Trubetzkoy,

Meillet) or they are regarded as pure nasalised vowels K, õ where the nasal

expiratory stream flows during the whole period of oral resonance (Komárek 1969: 22). Their rise may be associated with a

vocalic dissolution of medial clusters -mb-, -nd-,

-ng- that are common in Gallo-Romance languages. Palatal harmony. Laponoid languages often palatalised back vowels after

palatal consonants and changed back vowels o, a into their front counterparts e, ě. This change had nothing to do

with Uralic palatal synharmonism that resulted from

umlaut shift after the dephonologisation of rounded

vowels. Their palatalisation was not associated

with balancing front and back vowels in neighbouring syllables but had a

cause in the dissociation of the palatal component in the preceding

consonant.

Table 145. Vowel systems of European Laponoids Table 145 shows

a quadrangular layout of vowel systems in Gallo-Romance, Celtic, Slavonic and

Saamic languages. The two systems on the left

distinguish the inner rectangle of short vowels i, u, e, o. In Old Slavic short

vowels i, u turned into

ultra-short vowels ь, ъ. The outer rectangle is formed by long vowels i, u, ě, a or ī, ū, ā, ē. As far as open vowels are

concerned, Slavonic and Q-Celtic (Goidelic)

languages carried out shifts a, o

> o and ā, ō > ā. The long vowel a/ā has its palatal

counterpart in the open vowel ě or ē. Their open pronunciation does not

justify transcribing their vocalic quality in Lappish

by æ, . The closed rounded ū usually lost its rounding

and was pronounced as y. Most Q-Celtic vowels had

their nasal counterparts arisen from combinations of vowels with the

following clusters -nt, -nk (Bednarczuk

1988: II, 652, 656, 658). Nasal vowels appear in Lappish, Polabian Drevan, Polish,

Venetian, Gallo-Romance and Raeto-Romance dialects. Projections of Proto-Gallic into

Gallo-Romance dialects can be observed in nasal vowels, satemisation,

palatalisation, unrounded

variants of y/ū < u. Gallo-Italian dialects in Italy

are remarkable for fronting and unrounding u/ū. Indo-European u/ū is reflected in Old Bulgarian and

Church Slavonic as y and Greek (Aeolic) ü. In the Raeto-Romance

group their lawful reflex was ü/i while Gallo-Romance dialects rendered them as ü or u. In (from P. Bělíček: Prehistoric Dialects, |

The Lingual

Phonology of Sanids,

Pygmids, Lappids, Annamites and Sinids The Lappic type

of phonologies is constituted by lingual languages with a non-pulmonic lingual type of consonantism

(Table 7). It produces sounds by ‘a sucking action of the tongue’ that releases ‘a lingual ingressive airstream mechanism’.4 Its typical

representatives are clicks that are uttered with ‘a double closure in the

vocal cavity and an egressive

airstream following the release of the posterior

closure’.5 Further definitions explained them as

‘obstruents articulated with two closures

(points of contact) in the mouth, one forward and one at the back.’6 Clicks

with a clear sucking sound effect appear only in Khoisan

languages of Clicks look incompatible with consonantisms of other African languages but local toponymy in the Namibian neighbourhood abounds in many

place names starting with ts- and tc-. They must be estimated as dephonologised

and garbled clicks. Their sucking sounds resemble the pronunciation of

palatals and sibilant s-affricates, so it is possible that they were applied

as their substitutes in the languages of African Pygmies. Their consonantism teems with palatals, postalveolars

and sibilant affricates. Its phonemes in neighbouring dialects are rewritten

as palatal /by dy gy/ and velarised

affricates /pγ tγ

kγ qγ/.

Such phonological systems acted as ideal Palaeolithic archetypes but owing to

mixing words of different origin in mixed regional domains, they were

integrated into neighbouring hybrid unities. In most cases they were

reproduced as imprints or dephonologised

substitutes.

Table 7. The glottalic and lingual phonology

The Isolating and Reduplicative Morphology of Sanids,

Pygmids, Lappids, Annamites and Sinids Classical historical grammar fulminated

thousands of sound shifts but brought few testimonies of similar radical changes

in grammar, accidence and syntax. Phonological repertories tend to exhibit

radical innovations but they remain unparalleled in other linguistic aspects.

In cultural evolution most grammatical categories remain relatively untouched

and adopt mutations only in suffixal morphemes.

This discrepancy is removed if linguistic analysis focuses on spoken dialects

instead of the official written standard of national languages. This is

another good reason for promoting linguistic typological studies that do not

restrict their focus to describing individual language structures but build

bridges between tongues with similar types of traits. The phonological repertory of Lappids was preserved best among Sanids

in

Table 8. The grammatical morphology of Lappicm,

Sanic and Sinic brachycephals with incineration burials Elementary grammatical systems fall into

three types of nominal and verbal morphology. The gender-oriented morphology is

attributable to the language family of tall dolichocephals

with hand-axe industry and vegetal subsistence. In its original appearance

documented in African, Melanesian and Australian Negrids

it partitioned nouns into classes of animate, inanimate, vegetal and arboreal

classes. These classed were distinguished by prefixes put in front of nouns.

In the Horn of Africa their family ran upon Asiatic races with agglutinating

language structures and transitioned to suffixing morphology of inflecting

type. The group of Asiatic plant-gatherers, hoe-cultivators and

agriculturalists reduced the system of twelve nominal classifiers to the

opposition of animate and inanimate nouns. Their category included humans,

animals, animistic spirits as well as sacral deities. (from

P. Bělíček: The Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, p.

35-36) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||