|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

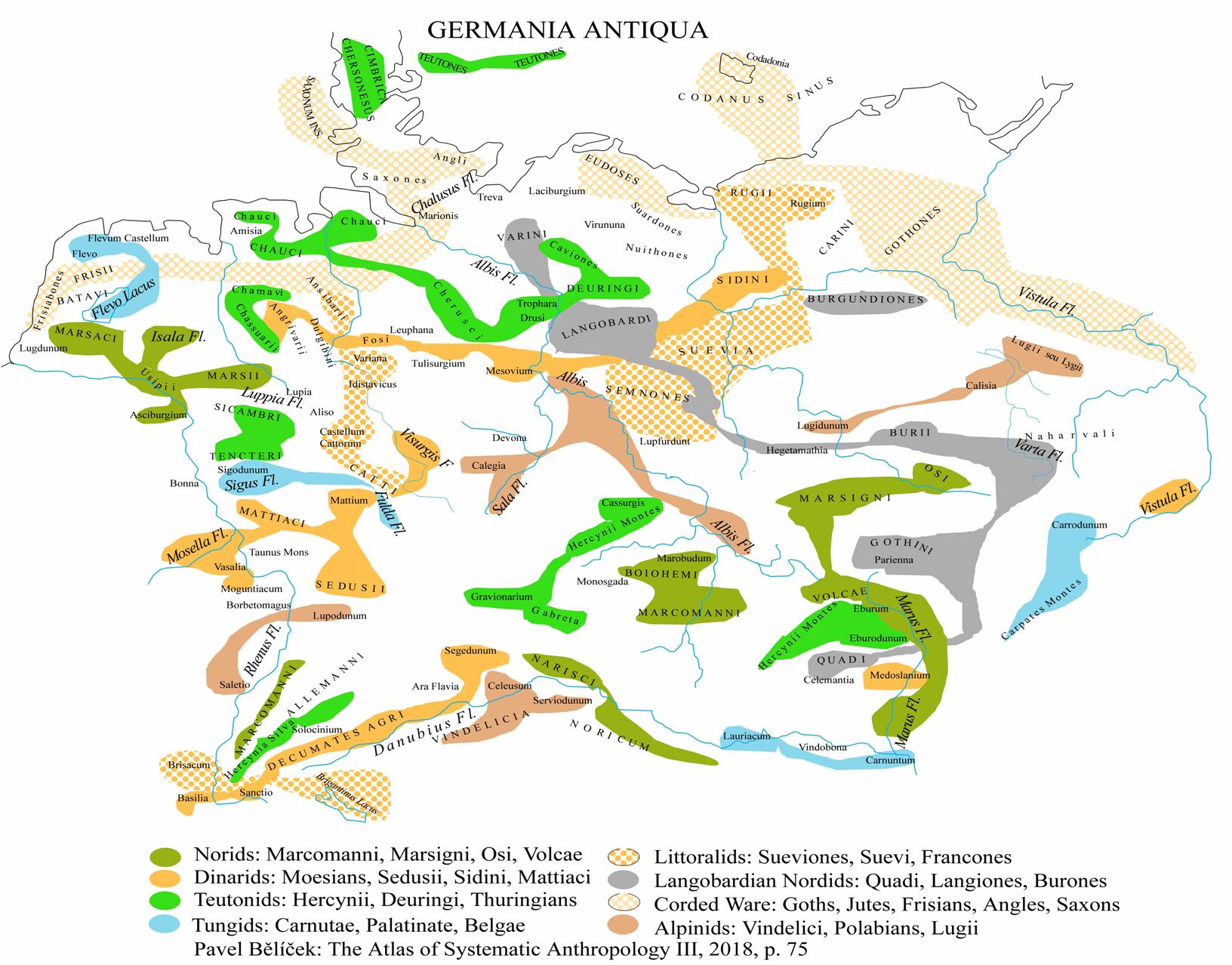

The Tribal Groups of Ancient Germania Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The tribes and

races of ancient Germania (from P. Bělíček: The

Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, Map 16, p. 75) |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Germanic genealogies have to be revisited

from the archaeological point of view. Germanic ancestors came to western

Europe from the east with three Microlithic cultures. The northern stream was

represented by Maglemosians (c. 9000-6000 BC) and the central Hercynian stream was conducted

by the Beuronians or Tardenoisians (7450-7000 BP). The southern Danubian stream was of earlier origin, its

first pioneers were Magdalenians (17,000 BP), who specialised as reindeer hunters. Their territories were

later occupied by two affiliated groups of microlithic flake tool

assemblages, at first the Azilians (14,000-10,000

BP) and then the Sauveterrians (8500-6500

BC). What united these filial cultures and

waves of migrations into one group was a similar composition of tribal

phratries. Their migration tracks seemed to multiply the basic five of

ethnonyms alluding to the phratries of Cimbrians, Teutons, Turanids, Germans

and Casites (Table 17). Such paradigm of ethnonymic associations was roughly

applicable also to microlithic sites in

Map 15. Cimbrian settlements after Maglemosian, Beuronian and

Sauveterrian colonisations The Taxonomic Disambiguation of the Germanic Peoples

The major crux in Germanic philology is the ethnic identity of

Germans, who are classified as one of Indo-European families but exhibit many

heterogeneous cultural traits. According to Tacit’s genealogies, Germans

descended from Tuisto, his son Mannus and three grandsons Irmin, Istvo and Ingvo: “the God Tuisto sprang from the earth, … he and his son

Mannus were the founders of the race. To Mannus they ascribe three sons,

whose names are borne respectively by the Ingæuones next to the

ocean, the Herminones in the middle of the country, and the Istæuones in the rest of it.”1 Modern philology prefers to spell Ingæuones as

Ingaevones and Istæuones as

Istvaeones. Jacob Grimm2 anticipated modern interpretations by

identifying the Ingaevones with the Saxons, the Istvaeones with

the Franks, and the Herminones with the Thuringians.3 His conclusions were further

developed by Friedrich Maurer4, who identified Germanic

tribes with Herminonen and divided

them into subfamilies of Teutonen, Istväonen, Ingväonen and Illevionen.

Tacit was aware that

contemporary Germanic populations included heterogeneous ethnic enclaves that

defended their own claims to Tuisto’s heirdom: “Others, with true

mythological license, give the deity several more sons, from whom are derived

more tribal names, such as Marsians, Gambrivians, Suabians, and Vandals; and

these names are both genuine and ancient.”5 They reflected the state of many

disconnected chieftaincies competing for hegemony in the Fallacies

of royal genealogies. Another account of Germanic genealogies was given

by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis historia. In his view the Herminones and Hermunduri descended

from the same line of descent as Mannus. Their stock encompassed also

the tribes of Chatti, Cherusci, and Suebi.7 Jacob Grim derived the origin of Istvaeones from a hero Ask featuring in Norse mythology. He

mentioned passages from Historia Brittonum by Nennius, where a certain Escio

was counted as an ancestor of the Istvaeones. In our view such genealogies

evolved from royal catalogues of ruling dynasties that were composed as an

assemblage of several incoherent pantheons. Their purpose was to subordinate

the deities of subjugated ethnicities to the supreme god of the reigning

clan. This deception was construed by adopting them as step-sons into the

family of their earliest ancestor celebrated as the supreme divinity. In

ancient Germanic genealogies have to

be revisited from the archaeological point of view. Germanic ancestors came

to western Europe from the east with three Microlithic cultures. The northern

stream was represented by Maglemosians (c.

9000-6000 BC) and the central Hercynian stream was conducted by the

Beuronians or Tardenoisians (7450-7000

BP). The southern Danubian stream was of earlier origin, its first pioneers

were Magdalenians (17,000 BP), who specialised as reindeer hunters. Their territories were

later occupied by two affiliated groups of microlithic flake tool

assemblages, at first the Azilians (14,000-10,000 BP) and then the Sauveterrians (8500-6500 BC). What united these filial cultures and waves of

migrations into one group was a similar composition of tribal phratries.

Their migration tracks seemed to multiply the basic five of ethnonyms

alluding to the phratries of Cimbrians, Teutons, Turanids, Germans and

Casites (Table 17). Such paradigm of ethnonymic associations was roughly

applicable also to microlithic sites in The Ethnic Substrates of Germanic Dialectology

The German linguist Friedrich Maurer took Tacit’s legend about Tuisto

and combined it with Pliny’s reports about Mannus and [H]illeviones.1 Their synthesis resulted in a

widely-accepted classification of Germanic languages and dialects.2 It counted with the mythic tripartition splitting Germanic nations into Istvaeonic and Ingvaeonic and Irminonic

tribes but included also a less reliably evidenced branch of Illeviones. His Irminones encompassed the Elbe Germanic group

headed by Thuringians, Bavarians and Alamanni. The core of Ingvaeones was formed by the North Sea Germanic people, who consisted of

Frisians, Angles and Saxons. The subgroup of Istvaeones provided a

convenient label for the Weser-Rhine Germanic branch uniting chiefly Franks

and Chatti (Graph 1). His considerations built a passable bridge between

ancient Latin historiography and modern Germanic philology inclusive of

dialectology.

Graph 1.

Friedrich Maurer’s subcategorisation

of Germanic language families Maurer’s

contributions influenced Germanic dialectology but suffered from classical

preconceptions of Germanic historical grammar. His elucidation

of Germanic languages consisted of one-sided misinterpretations of Germanic

myths grafted on a sound rational partitioning of dialectal groupings. The

second prominent founder of Germanic dialectology appeared in Ferdinand Wrede1, who elaborated the Irminonic theory

of Elbe Germanic dialects to perfection. Their followers added several

substantial refinements.2 They

realised that the Ingaeonic covered the block of Goths, Jutes and Frisians

inclusive of Dutch, Jutlandic and Low German. The Istvaeonic subfamily was

dubbed as Weser-Rhein-Germanisch and its domain covered the Franconian

family with West Central German dialects. Illeviones were posed as a

hypothetical group covering Silesians and Oder-Vistula subfamily. Fruitful

results were brought especially by the popular theory of Ingvaeonisms in

Germanic dialects. It developed theoretical considerations on the Ingvaeonic

origin of Anglo-Saxons.3 The fallacy of prehistoric

nations. Maurer’s errors require a digression to contrasts between the ancient

and modern concept of a tribe. Modern authors suffer from an irresistible inclination to conceive

prehistoric tribes as large united compact nations coextensive with the

present-day republics. They are liable to discard all indications of inner

ethnic plurality and deny all long-range links between continental tribes. In

opposition to their biased views, the ancients acknowledged the surviving

state of diversity and saw genetic consanguinity between remote related

cognates. Their geographers did not mind linking different Eurasian factions

of Scythians, Sarmatians, Kimmerians, Pelasgians or Hyperboreans. They

confirmed immense geographical diversity and scattered distribution of ethnic

groups. The ancient world did not see any compact nations and homogeneous

countries without a rich internal stratification of castes, classes, enclaves

and minorities. In their eyes ancients Jutlandic and Subalpine Cimbri

were related to the Kimmerioi4

on the |

|

Archaeological Roots of

Germanic Minorities

Turanids. Mesolithic cultures with microlith implements

drifted from

Table

20. The

varieties of European Turcoids, Cimbrids, Germanics and Punoids

The Germanic newcomers were Epi-Maglemosian ‘bog-people’, who

inherited the Y-DNA haplogroup R1a-M420. They went fishing in boats and used

canoes as coffins for burials of their dead. Their Madgalenian relatives in

Table 21. The

comparative ethnonymy of Turanids and Turcoid tribes Cimbroid cultures exhibited features

characteristic of peoples producing Epi-Magdalenian, Epi-Azilian and

Epi-Tardenoisian microlithic tools. Their descendants are usually mentioned

in historical annals as Celtiberians, Eburones, Eburovices,

Etruscans, Irish Iverni or Hiberni. Their life-style differed a

lot from Punids, who were renowned as maritime fishermen and pirates. They lived in

cliff-dwellings that were hewn in coastal crags and accessed through vertical

shafts. One of their branches was formed by Phoenicians who specialised in

seafaring. The ancients believed that they came to the Prehistoric Germanic tribes

were associated with Gotho-Frisian Nordids only by contact vicinity and

integrated into European phenotypes as Mediterranids or Subnordids. More

influential impact was perceptible in the constitution of Romance, Italic,

Slavonic and Baltic languages families. They descended from Gravettian and

Lusatian colonisations that took their course as peaceful infiltrations. They

inoculated the Gothonic core of Indo-European and differentiated from its

standard by importing nasal vowels, satem shifts, palatal stops and

affricates. Traditional doctrines classify them as brachycephalous Subnordids

and describe their tongues as genuine Indo-European languages. Their

structural import consisted in numerous innovative additions such as

masculine o-stems and feminine a-stems. They contrasted with

the inflective morphology of Anatolian Proto-Indo-Europeans, who

distinguished only animate and inanimate gender and recognised only neutral i-stems

with nominative s-plurals. Extract from Pavel

Bělíček: The

Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, pp. 145-86. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1 Tacit, Germ. 2.

2 Jacob Grimm: Deutsche Mythologie Göttingen, 1835.

3 William Stubbs: Constitutional History

of England, I, 1880, p. 38.

4 Friedrich Maurer: Nordgermanen und Alemannen: Studien

zur germanischen und frühdeutschen Sprach-geschichte, Stammes- und

Volkskunde.

5 Tacit, Germ. 2.

6 Plinius,

Naturalis historia

37, 35; Ptolemaeus 2, 11, 9.

7 Plinius,

Naturalis historia 4, 100.

1 Plinius, Naturalis historia

I, 1.

2 Friedrich Maurer: Nordgermanen und Alemannen: Studien

zur germanischen und frühdeutschen Sprach-geschichte, Stammes- und

Volkskunde. Bern: A. Francke, 1952, pp. 175-178.

1 Ferdinand Wrede: Ingwäonisch und

Westgermanisch. Zeitschrift für deutsche Mundarten, 1924: 270-283; V. M.

Zhirmunski: Deutsche Mundartkunde. Berlin 1962.

2 Carol Henriksen – Johan van der Auwera:

1. The Germanic Languages. In: Johan van der Auwera, ed. The

Germanic Languages. London, New York: Routledge, 1994, 2013, pp. 1-18.

p. 9.

3 Ferdinand Wrede: Ingwäonisch und

Westgermanisch. Zeitschrift für deutsche Mundarten, 1924: 270-283; T.

Frings: Grundlegung einer Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. Halle 1957.;

V.

M. Zhirmunski: Deutsche Mundartkunde. Berlin 1962, p. 50-51.

4 Strabo, Geography 7.2.2; Diodorus

Siculus, Bibl.5.32.4; Plutarch, Vit.Mar. 11.11.