|

|

The

Traditional Views of Indo-European Unity

The Nordic and Danubian Gothids as the Core

of Indo-Europeans

Traditional concepts of European tribes insist on a

sort of holistic isolationism that identifies tribes with nations cast like

ingots in the mould of medieval monarchies. A more sophisticated view divides

Gothids into phratries (Jutes, Frisians, Angles, Saxons) denoted as

Endo-Gothids, and lineages of migration streams designated as Syn-Gothids.

Streams jut out of the cradleland of the tribal diaspora like tentacles of an

octopus or branches of a genealogic tree growing out of one trunk. The entire

genealogic tree might be referred to as a union of Pan-Gothids (Table 11).

The common

Gothonic starting-point may be found in the farmers of the Danubian Linear

Ware (5500–4500 BC), who seem to have coincided with the Y-DNA haplogroup

I2-M423 in Central Europe. The Funnelbeaker or Trichterbecher

culture (c. 4300 BC – 2800 BC) occupied seats that were later seized by

colonists of the Bootaxt people with the Corded Ware (2900 BC – circa

2350). They also showed inclinations to agriculture although their earliest

excavated sites depict them as littoral sand-dune dwellers, who built

characteristic Gothic wurts or Frisian terps surrounded by

shell midden. Their ancestry may be traced back to the earlier past of the

Campignian shell midden complex (cca 10 000 BC)

and the Portuguese Muge culture. The former term was originally coined by C. Schuchhardt but now it is

neglected as less common. Its use however proves requisite for sheltering

early migrations of the Corded Ware in North

Asia. Numerous shell dump heaps were

characteristic of the Japanese Jomon culture (16 000 BP) with

cord-marked pottery. They were created by beachcombing littoralists gathering

mussel shell on seaside beaches. Their original Y-DNA haplogroup must be of I1-M253

type corresponding to the blood group O and tall dolichocephalous stature.

The area of the Portuguese Muge culture is sometimes interpreted as a

possible starting point of the Bell-Beaker folk (2900 – 1800 BC). Its

southern promontories pursued Atlantic coastlines as far as the Gulf of Guinea,

Angola and South Africa.

|

Pan-Gothids

|

Campignian Littoralids, Danubian

Europids, Scandinavian Nordids

|

|

Northern Gothids

|

Goths/Jutes, Frisians, Angles, Saxons

with the Y-hg I1

|

|

Southern

Gothids

|

Rugians, Franks and Swabians Littoralids with the Y-hg I1

|

|

Danubian Europids

|

Langobards, Langiones, Burones, Quadi

with the Y-hg I2

|

|

Syn-Gothids

|

northern Finnish stream, central

Prussian stream, southern Balkan stream

|

|

Finnish stream

|

Hiittinen, Hiettanen, Gydan, Okhotsk, Hokaido, Haida

|

|

Prussian stream

|

Prussian, Yotvingian, Permiac, Udmurt,

Khitans in Kitai,

|

|

Balkan stream

|

Getes, Khotan, Khotanese, Gotho-Tocharians,

Masagetes, Brahmans, Khattriyas

|

Table 11. The systematic classification of Gothoid phratries

and tribes

Archaeological finds and population

genetics prove that bearers of the Y-haplogroup I1 must be identified with the

Corded Ware in the north and the Bell-Beaker Folk in the south. The

beginnings of the Corded Ware in West Europe are dated back

to 2900 BC but its eastward travels ended in the Far East. Its final

product became known as the cord-marked pottery of the Japanese Jōmon

culture (13,000 BC or 16,000 BP). Such a temporal incongruence may be

explained by deriving Gotho-Frisian tribes from the earlier Campignian

culture of shell midden beachcombers. On the Iberian

Peninsula they had closely related kinsmen in Franco-Swabian

littoralids, who had earlier forerunners in the Asturian culture (9280±440 BP) in northwest Spain and its Portuguese

counterpart referred to as the Mugem culture. Both used to produce bell-shaped

beakers and imported their patterns to la cultura campaniforme in

western coasts of Africa as far as Guinea and Angola. The

cord-impressed ceramic travelled throughout the Middle East also to the

Pakistani Mehrgarh culture (9,500 BC) and the Vindhyas culture in India (10,000)

BC). Its migrations were accompanied by other characteristic traits: shell

midden heaps, longhouses on seaside sand-dunes, heavy macrolithic tools,

battle axes, dolichocephalous skulls, Europoid look and agricultural

dispositions tending to grow foxtail millet. Such circumstances support

Biasutti’s racial classification that denotes American littoralids (Columbidi,

Lagidi, Fuegidi).

The important point is that Preeuropidi

had reached the coasts of the Far East around 13,000 BC and

implanted an early version of Indo-European elocution in India. It were the

priestly caste of Brahmans and the royal caste of Kshatriyas who implanted

the seed of Indo-European Ursprache in India a long time

before the arrival of Aryas (1600 BC). As a consecution, Vedic Sanskrit may

regarded as a record of the Indo-European tongue before the arrival of the

Maglemosian culture (9000 BC) smuggled into Europe by the Mesolithic invasion

of Microlithic cultures of Turcoid origin and the Y-hg R1a. The trueborn

Europids spoke a vocalic language with three-morae vowels and triphthongs and

the opposition of voiced and surd voiceless consonants. The Germanic invaders

were false Europeans who infiltrated their speech with the opposition of aspirated

tenuis and lenis stops and Turcoid vowel harmony with front rounded vowels

that caused the effect of the Umlaut shifts.

Their archetypal differences were

manifested by absolutely incompatible phonologies and grammatical systems.

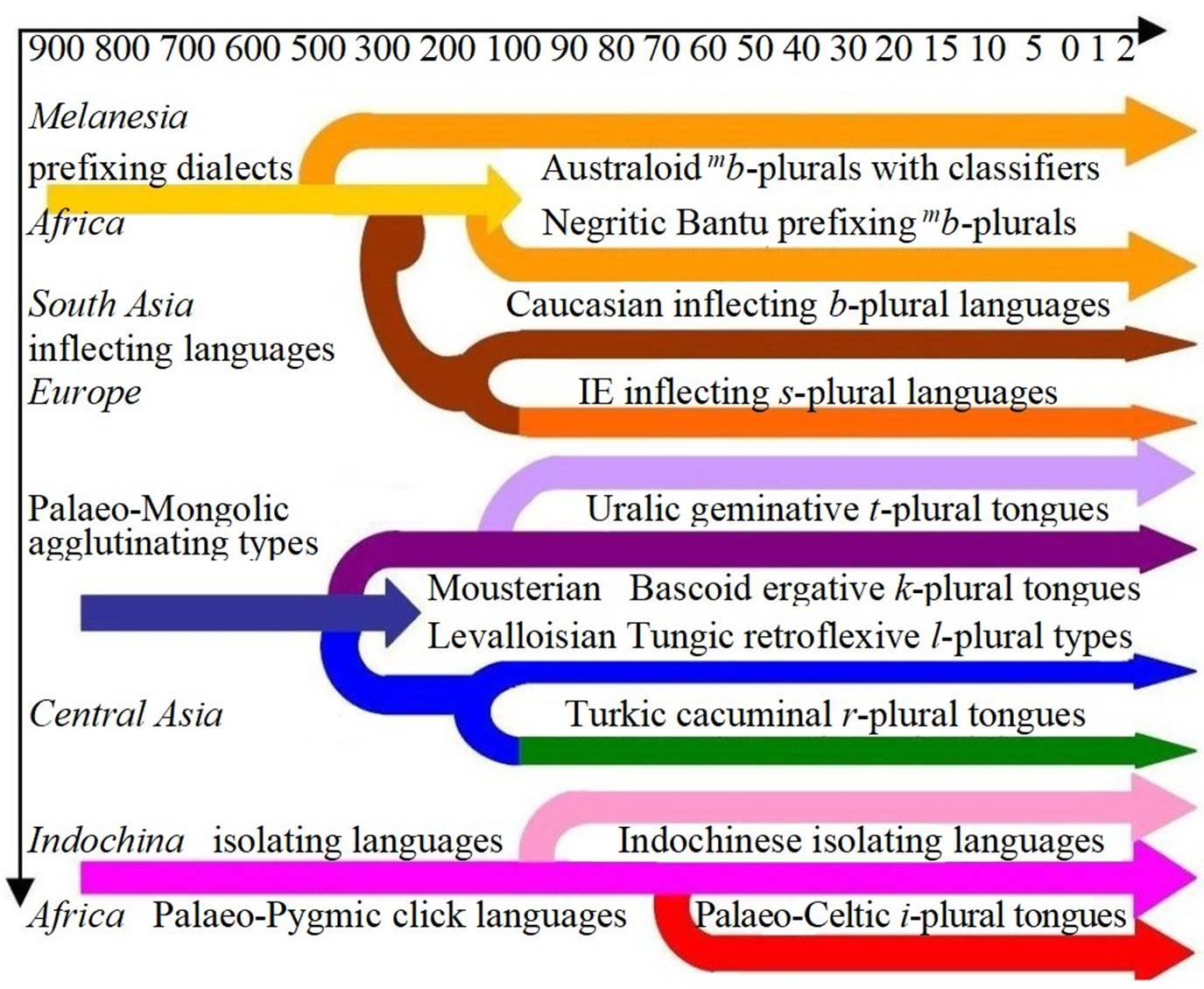

African Negrids, Asiatic Caucasoids and European Nordids applied cordal

languages, whose consonantism was based on the vibration of vocal cords

and the opposition of voiced and surd phonemes (Table 5). They pronounced

vocalic cordal phonemes based on open syllables and phonemes produced by

airstream passing through vibrating vocal cords. If there were any structural

changes, they were caused by mixing with Altaic agglutinating systems.

|

Negritic cordal phonology

Negrids with prenasalised stops

|

Acheulean cordal phonology

Caucasoids/Elamitoids/Gothonids

|

Indo-European cordal phonology

Europids/Gothids

|

|

short vowels: i e a o u

|

short vowels: i a u

|

short vowels: i a u

|

|

weak evidence of long vowels

and diphthongs

|

long vowels:

ī ā ū

diphthongs: ai au

|

long vowels: ī ā ū

diphthongs: ai au

|

|

no long diphthong or triphthong

|

long diphthongs: āi āu

|

long diphthongs: āi āu

|

|

voiced prenasals: mb- nd-

ŋg-

voiced plosives: b d g

|

voiced plosives: b d g

|

voiced plosives: b d g

voiced fricatives: v z h

|

|

surd prenasals: mp- nt- ŋk-

surd plosives: p t k

no consonant clusters

|

surd plosives: p t k

surd fricatives: f s χ

|

surd plosives: p t k

surd fricatives: f s χ

initial clusters: spr- str- skr- str-

|

|

voiced sonants:

j w l r

|

voiced sonants:

j w l r

|

voiced sonants:

j w l r

|

|

voiced nasals: m n ŋ

|

voiced nasals: m n

|

voiced nasals: m n

|

|

voiced trill r

|

voiced vibrant/trill: r

|

voiced vibrant/trill: r

|

Table 5.

The cordal phonology of dolichocephals

with macrolithic hand-axe industry

Table 5 demonstrates an organic growth of

IE phonology from the Ursprache of Elamitoid Caucasoids and its

incompatibility with Germanic innovations hiding away Turanid origins.

|

Gender-oriented morphology

Negrids with nominal classifiers

|

Gender-oriented morphology

Caucasoids/Elamitoids

|

Sex-based gender categories

Europids/Gothids

|

|

prefixing morphology

|

suffixing morphology

|

inflective morphology

|

|

noun classes/classifiers

prefixing formation

gender: animate/human – inanimate

gender class: vegetal – arboreal

|

nominal categories

suffixing gender formation:

animate/human – inanimate

|

nominal categories

suffixing gender formation:

animate/human – inanimate

|

|

number: singular mu- mo- li- e-

plural prefixes: ba- bi- mi- ma-

|

number: singular – plural

b/w-plurals

|

number: singular – plural – dual

s-plurals

|

|

cases: no cases

|

cases: absolutive – oblique

|

cases: nominative – accusative

|

|

voiced prenasals: mb- nd-

ŋg-

voiced plosives: b d g

|

voiced plosives: b d g

|

voiced plosives: b d g

voiced fricatives: v z h

|

|

word order: SVO

adjective attributes: NA

nominal attributes: NG

numeral attribution NNum

|

word order: SVO

adjective attributes: AN (NA)

nominal attributes: NG

numeral attribution NumN

|

word order: SVO

adjective attributes: AN (NA)

nominal attributes: NG

numeral attribution NumN

|

|

adjunctions: prepositions

conjuctions: prejunctions

|

adjunctions: prepositions

conjuctions: prejunctions

|

adjunctions: prepositions,

conjuctions: prejunctions

|

|

that-clauses

|

that-clauses

|

that-clauses

|

Table 8.

The nominal morphology of dolichocephals

with macrolithic hand-axe industry

Elementary grammatical systems fall into

three types of nominal and verbal morphology. The gender-oriented morphology

is attributable to the language family of tall dolichocephals with hand-axe

industry and vegetal subsistence. In its original appearance documented in

African, Melanesian and Australian Negrids it partitioned nouns into classes

of animate, inanimate, vegetal and arboreal classes. These classed were

distinguished by prefixes put in front of nouns. In the Horn of Africa their

family ran upon Asiatic races with agglutinating language structures and

transitioned to suffixing morphology of inflecting type. The group of Asiatic

plant-gatherers, hoe-cultivators and agriculturalists reduced the system of

twelve nominal classifiers to the opposition of animate and inanimate nouns.

Their category included humans, animals, animistic spirits as well as sacral

deities.

This categorisation survived

also in Anatolian tongues until their further expansion in the Balkans

encountered Gravettian tribes of Alpinids with sex-based gender

classifications. Their clash resulted in the rise of sex-based nominal gender

enriched by masculine o-stems and feminine a-stems. The core of

European Gothids accepted the dual opposition of masculine and feminine

gender but their core remained reluctant to their addition and continued to

adhere to nominal i-stems. Their subclasses coexisted with Caucasoid

vegetal u/w-stems that can be explained as remains of Caucasoid

b-plurals referring to agricultural crops and instruments of farming

activities. The classification of Indo-European thematic and athematic stems

may be regarded as a hold-over of ancient invasions and infiltrations

surviving in residual form in the territory of Europe. The sex-based

gender distinction of the suffixes -o and -a first appeared in

African Chadic and Ethiopian Galla languages and their spread all over Europe was due to the

Gravettian colonisation of short-sized brachycephals to the north. They were

embedded into the system of IE accidence as new thematic stems distinguishing

the masculine o-stems and feminine a-stems. The u-stems

penetrated into the IE word stock with the propagation of Neolithic farming

from the Fertile Crescent to the Danubian

river basin.

|

Eteo-dialects

|

|

Old

Indian

|

|

Allo-dialects

|

|

Indo-Negritic mb- nd-

ŋg-

|

→

|

Negritisms:

amb- and- ang-

|

|

|

|

Gothoid voiced b- d- g-

|

→

|

Gothoid

Sinisms: bh- dh- gh- nh-

|

←

|

bh-

dh- gh- nh- Sinic

|

|

Scythic ejectives p’ t’ k’

|

→

|

Scythoid

clusters: sp- st- sk- sn- sl- sr-

|

←

|

hp- ht-

hk- hn- hl- hr- Scythic

|

|

Scythised

cacuminals

|

→

|

cacuminal

clusters: spr- str- skr- zdr-

|

←

|

tr- dr- Turanic cacuminals

|

|

Scythised

laminals

|

→

|

laminal

clusters: spl- stl- skl- sn- sm- sl-

|

←

|

tl-

dl- Tungusoid

laminals

|

|

Scythic

implosives ɓ̥ ɗ̥ ɠ̊

|

→

|

Scythoid

surd plosives: b d g

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sanoid

clicks and s-affricates: c z ʃ ʒ

|

←

|

tc-

dc-

Sanism

|

|

|

|

Lappisms:

by- dy- gy- ny- py- ty- ky-

|

←

|

by-

dy- gy- ny- py- ty- ky- Lappic

|

|

|

|

Tungisms:

tl- dl-, ʈ- ɖ-, ṭ- ḍ- ṇ- ṣ- ẓ-

ḷ- ɾ̣- ɹ̣-

|

←

|

ʈ- ɖ- ɳ-

ʂ- ʐ- ɻ- Dravido-Tungic

|

|

|

|

Turanisms:

tr- dr-, ʈ- ɖ-, ṭ- ḍ- ṇ- ṣ- ẓ-

ḷ- ɾ̣- ɹ̣-

|

←

|

ʈ- ɖ- ɳ-

ʂ- ʐ- ɻ- Dravido-Turanic

|

Table 10. Conservative

embeddings and regressive intrusions in Old Indian consonantism

The first autochthons in India were Negrids, whose

word stock with prenasalised stops was absorbed into Sanskrit by adding the

prothetic vowel a-. As a result, the initial phonemes /mb- nd-

ŋg-/ were encapsulated into its norm as amb-,

and- and ang-. After

the arrival of black-skinned Negrids of Oldowan origin there appeared a

colonisation of Acheulean hand-axe cultures (800,000 BP) that discarded

prenasalisation and replaced the prefixing ba-plurals of human beings

with suffixal b-plurals as in Dravidian Gadaba and Gutob in North

Indian Punjab. In dialects of Central Asia they accompanied the

ethnonyms of Caspii and Lullubi.

The first Indo-European

newcomers were Campignian Littoralists (10,000 BC) with cordmarked pottery,

who colonized the Vindhya Range in Gujarat. They were not

populous enough to Europeanise the entire Indian subcontinent but they

disposed of an advanced educated religious tradition that enabled their

Brahman descendants to get hold of an enviable scriptural monopoly. They

managed to reinforce it as an official administrative standard used in

religious rites. Their integration involved embedding the Brahmanic

Proto-Gothic voiced plosives b, d, g into the local

phonological framework with murmured breathed stops bh-, dh-,

gh-. Their heritage may be ascribed to

Acheuloid racial groups with Y-haplogroups G and H, whose occurrence

culminates in the Indian subcontinent.

The Dravidian element in Old

Indian was represented by retroflex consonants written as ṭ, ḍ, ṇ,

ṣ, ẓ, ḷ, ɾ̣, ɹ̣ but the IPA standard records

them as /ʈ, ɖ ,

ɳ, ʂ, ʐ, ɭ, ɻ, ɽ/. They were

notable for pronunciation with the tip of the tongue bent backwards in a concave or curled shape. Their use was obliterated in most language

families but their remains often survive in the affricates tr- dr-,

tl- and dl-. Most types of notation do not distinguish

their apical and laminal pronunciation. The laminal retroflex consonants were

characteristic of Tungusoid fishermen, who disseminated them in Eurasia with Aurignacian colonisations around 40,000 BP. The apical or

cacuminal retroflex consonants must have been imported by Turcoid cultures

with microlithic flake-tools around 11,000 BC.

|

|

Every Indo-European family consists of one dominant core that forms

its pure-blooded ‘eteo-race’ and several concomitant subraces. Inherent

subraces are consanguine ‘endo-races’, heterogeneous subraces are

‘allo-races’, alien invaders who acculturated as cohabitants of the dominant

eteo-race. So Angles and Saxons belonged to the connate ‘endo-races’ of Jutes

and Frisians. On the other hand, the Celts were only a disparate and

inorganic collection of alien ‘allo-races’ that huddled around the eteo-races

of Gauls and Gaels. Their territories overlapped with plantations of

Magdalenian Iberians, Epi-Cardial Pelasgoids, Poladan lake-dwellers, Welsh

sheep-breeders as well as Scottish cairn- and broch-builders. Despite regular

intertribal skirmishes nobody ousted, expelled and exterminated anyone, all

prehistoric migrations occurred as inimical but relatively peaceful

infiltrations as ancient tribes occupied different natural ecotypes.

The principal thesis assumes that the greatest part

of the Indo-European lexical substance was created by Europids (Danubian

Gothids) but relevant contributions were made also by megalith-builders,

Alpinids and Mediterranids. An intensive impact was enforced only by

colonisations of Magdalenian Iberids and Maglemosian Cimbrids (Table 17).

Maglemosians gave rise to Germanic languages and triggered the Great

Consonant Shift in Common Germanic. The cultural influence of Mediterranids

was imported mainly by Aurignacians, Madgalenians and Epi-Cardial Pelasgids

(Table 15). Their linguistic loans partly survived only in Lydian and Carian.

Alpinids created the domains of Celtic, Albanian and Slavic languages that

are remarkable for patatalisation, satemisation, nasal vowels, tonal prosody

and pitch accents.

Pseudo-Indo-European

allochthones = Mediterranids + Ugrids/Macro-Dinarids + Norids + Alpinids

Ugro-Scythoids

or Macro-Dinarids = giant brachycephalous beehive-dwellers with convex

aquiline noses

Norids = taller

(meso-)brachycephals with four-pitch-roof marquee tents

Alpinids/Lappids = short

brachycephalous semidugout-dwellers with concave noses

Mediterranids = slender gracile mesocephals with small feet, narrow

eye-fissure and high cheekbones

Tungids =

slender gracile mesocephals with residual epicanthus and slanting eyes; they

lived in tall tepee tents with crossed tent-poles and built anthropomorphous

stelae

Pelasgids =

slender gracile mesocephals with dark hair and dark brown eyes; they lived in

conical roundhouses/rondavels and used ochre burials with tall standing

stones (menhirs)

Turanids =

slender gracile mesocephals who lived in rock shelters and artificial rockcut

caves

Mediterranids = Euro-Turanids +

Euro-Tungids

Ugro-Scythoids

or Macro-Dinarids →

Epi-Aterian Baskids + tumuli-grave

Dinarids + kurgan-builders

Norids ← Hallstattians (900 BC) ← Sarmatids ← Sintashta

culture (2,100 BC) ← Comb Ware (6,000 BC)

Euro-Tungids → Levalloisian (95,000 BP) + Cardial Ware

(6,400 BC) + Aurignacian (37,000 BC)

Alpinids

→ Gravettians (33,000 BP) + Stroked Ware (4,500 BC) +

Cinerary Urns + Lusatians (1150 BC)

Table 12. Pseudo-Indo-European peoples (Allo-Europoids) of

allochthonous Asiatic origin

Basco-Scytho-Ugric cultural morphology

Funeral architecture: dolmen, cairn (Britain), round barrow, tholos

(Mycenaean),

Monumental architecture: broch (Scotland), henge (Britain), nuraghe (Sardinia), talailot (Menorca)

Baskids, megalith-builders: [Vascones – Vasates – Sotiates

(Pyrenees)] + [Agri Decumates – Mediomatrici

– Pictones – Pictavi (North France)] + [Picts – Scots – Ogres (Britain)] + [Scandza – Varangians (Scandinavia)]

Dinarids, tumulus cultures, Hügelgräber: [Mattiaci – Seducii – Angrivarii

– Fosi (West Germany)] + [Picentes, Peucetians –

Messapians (Italy)]

Cyclopes: [Mycenaeans – Argolids] + [Mysians (Anatolia) – Bessi – Macedonians –

Moesians]

Scythoids: [Abkhaz – Abazin] + [Matiana – Media – Scythia – Sogdiana – Sacae]

Table 18. A survey of Bascoid

ethnonyms and cultural morphology

Mediterranids.

The traditional category of Mediterranids is firmly attached to the territory

north of the Mediterranean Sea but

it evokes association with similar human phenotypes evidenced in northern Europe as

well as in India and

other parts of Asia. Its

semantic content is too broad and should be narrowed to two closely-related

brotherly races of prehistoric nomadic fishers: Tungids with long prismatic

leptolithic industry and Turanids with small triangular or trapezoid flakes

inserted into bone hafts. These genuine varieties of Mediterranids are noted

for exhibiting mesocephalic skull indices and high hypsicranic faces. The

absence of these features makes it possible to distinguish them clearly from

false Mediterranids (Atlanto-Mediterranids, North

Atlantids, Berids) with long-headed crania.

Euro-Tungids (also

called Ladogans, Baltids, Karelians, Hyperboreans; nomadic fishermen,

lacustrine lake-dwellers, pole-dwellings, tepee huts, Finnish steep-sloping

chalets with tepee-like gables, Lappish huts laevu and goahti,

lakeside fishermen, acorn-eaters (?), ABO group B, low frequencies of Y-hg

C):

N1 Karelian Tungids: Karelians

(Karjalabotn, Kirjaland),

NW Latvian Tungids:

Baldayskaya Range → Baltinava → Latgalians

→ Latvia →

Curones,

W1 Polochan

Tungids: Polochans, Poloczanians (at Polotsk, Belarusia) → Lithuanians → Belostok → Polans (also

Polanes, Polanians, Polish Polanie in the Warta river basin) → Płońsk-Bielsk → Poel → Flensburg

→ Danes (Dani)

W2 Polonian Tungids: Volga

Bulgars → Polovtsi (Polish Połowcy, Plauci) → Polans

(Opolans), Połomia →

Bolokhoveni,

W3 Euro-Tungids: Plone

→ Belesane → Ostfalen (Ostfalia)

→ Westfalen → Belgium (Belgica,

Belginum) → Bellovaci → Flemish

Flanders (Flandria) → Belgae

(south England).

W4 Euro-Tungids: Balti

(Romania) ← Ipoly, Pilis, Ipel’ (Hungary, Slovakia) ← Pálava

(Moravia) ← Tuenagove ← Blesigove ← Pfalz (Germany),

NW Pelasgids:

Pelasgians (Pelasgiotes) → Belegezites

(Thessaly) → Illyri (Illyrioi, Illyrii)

→ Dalmatians → Carinthians (Slovenes in Austria and Slovenia)

Table 13. The colonisations and

migration routes of Aurignacian Tungids in

Europe

Tungusoid

Mediterranids. The group of European Tungids is not

documented satisfactorily by recent anthropometric measurements because it

dates back to archaic Palaeolithic eras. The core of their populations

arrived to west Europe with

Aurignacian colonists from the Black Sea

around 38,000 BC. Their heralds bore the original Tungusic Y-haplogroup C but

with the progress of time they declined to zero values. Its rates were not

increased by the Cortaillod-Chaséen and the Latenian revival, either. Neither

of them brought a new genetic infusion of this genome from the east. As the

Latenian/La Tène culture ranges from the Danubian estuary to France, Brittany and Ireland, the

Pontic seaboard looks like the possible starting-point of its influx. As a

consequence, we ought to adopt a more plausible hypothesis that the Latenian

bloom should be estimated as a cultural revitalisation of Chasseén

lake-dwellers propagating in eastward as well as westward direction. Provable

conclusions indicate only repeated Latenian passages to Britain and Ireland from

the boundary region between Switzerland, Italy and France.

Toponymic studies suggest the following ethnic migrations of the Pontic

homeland.

The earliest ancestors of

Spanish and West-European Iberids can be seen in Magdalenians, known as

reindeer hunters with microlithic tool implements. The typical representative

of their race was Chancelade man, documented also in ostial finds from

Laugerie-Basse and the Duruthy cave near Sorde-l'Abbaye. Chancelade

man exhibited a narrow but tall and long cranium, tall and wide face,

prominent cheekbones, tall and narrow nose and high orbits. His burials,

however, displayed also some incompatible heterogeneous admixtures: ochre dye

characteristic of Aurignacian Tungids, and also some Europoid heritage.

Europoid elements were demonstrated especially in the strong chin and the

sagittal keel spanning along the suture between the parietal bones.

|

Mediterranids → Euro-Turanids + Euro-Tungids (Aurignacians) +

Euro-Pelasgids (Cardial Impresso)

Euro-Turanids (Mesolithic microlithic flake-tool

cultures of Turcoid descent) → boreal

Turanids (Maglemosians) + meridional

Turanids (Magdalenians)

|

|

Magdalenians

Iberids

Madgalenians

Kimbern

Ahrensburgian

Trønderids

Cambrians

Eburones

Hibernids

Ahrensburgian

Tardenoisians

|

→ Iberids (rockcut-dwellers, reindeer hunters,

burnished ware, Y-hg R1b, 17,000 BP)

→ Iberians + Eburones + Kimbern + Cambrians + Hibernids

→ Azilians (rock art, imprints of phalanges,

hepatomancy, 14,000 BP) > Cantabrians

→ Hamburgian complex (15,500 BP) > Ahrensburgians

(12,900 BP)

→ Ertebølle culture (ca 5300 BC) > Kimbern

(Himmerland) + Trønderids

→ Komsa culture in

western Norway (10,000 BC)

→ Creswellians (Y-hg R1b, 13,000 BP, British Cambria, Cumbri)

→ Seine-Oise-Marne group (> Eburones, 3100 BC, rock-cut gallery tombs)

→ Fomoire (Irish cliff-dwellers) + Hiberni,

inhabitants of rock shelters in Ireland

→ Tardenoisians (Y-hg R-U152, 8,000 BC)

→ Tyrrhenes (> Etruscans) + Siculi (>

Sicilians)

|

|

Dnieper-Donets

culture, Y-hg R1a → Swiderians

(11,000 BC) → Silesians

|

|

Maglemosians

Cimbrids

|

→ Cimbrids (bog people, fishers, pointed-base

pottery, Y-hg R1a, 9,000 BC)

→ Cimbrians + Teutons + Germans

|

Table 16. The genealogic branching of Microlithic Euro-Turanids

Extract from Pavel Bělíček: The

Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, pp. 7-16.

|

|