|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

The Earliest Ancestors of Acheulean, Yabrudian,

Caucasian and Elamite Languages Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

||||||||||||||

|

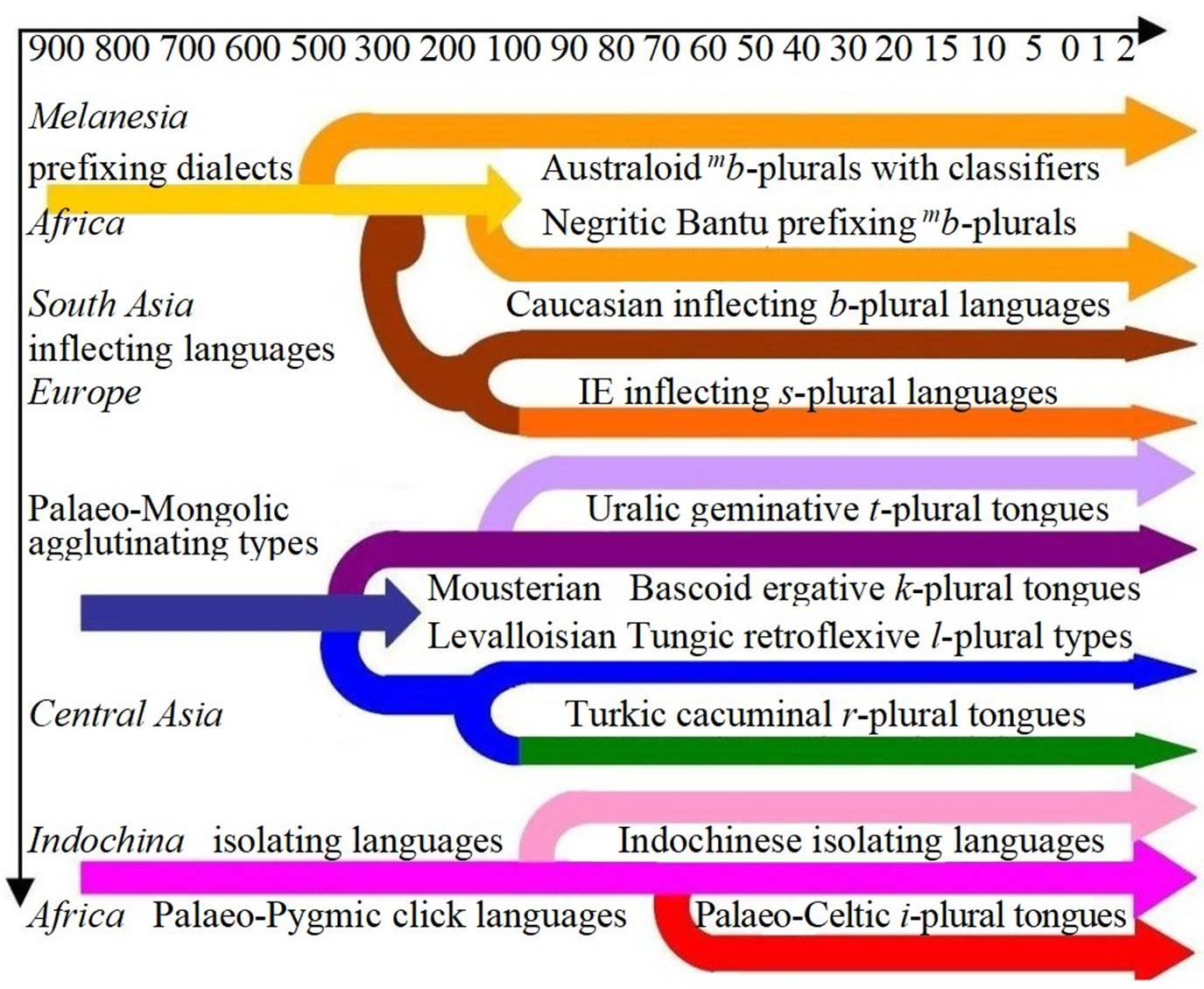

Table 1. The Systematic Glottogenesis of Human

Language Families |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

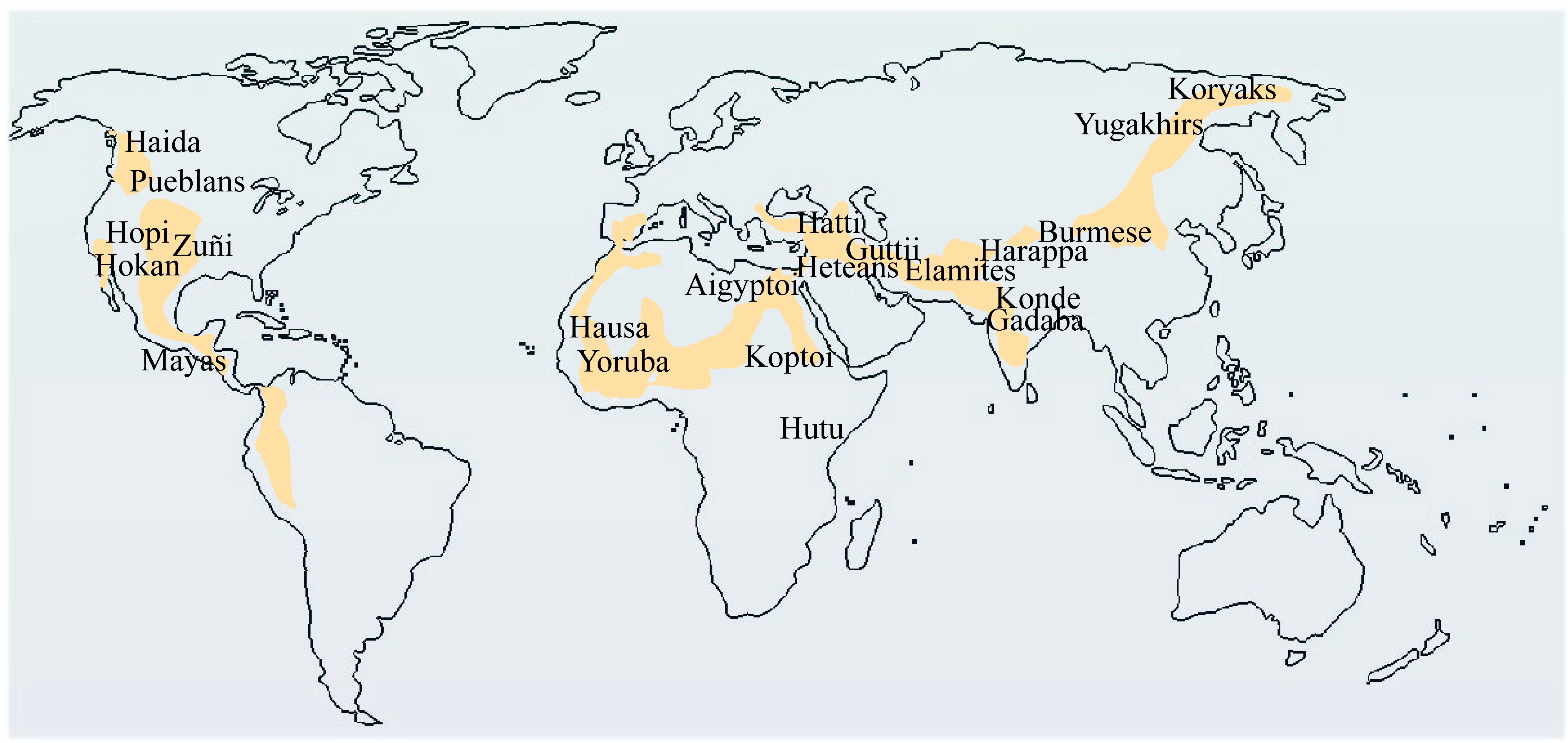

Map 1.

The Distribution of Ancient

Asiatic Language Families

Table 2. Renaming

Asiatic Language Families |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Map 2. The Distribution of Caucasoid

and Elamitoid Languages with b-plurals and Ergative Constructions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Elamite and Caucasoid Family of Languages

The problem of Caucasian proto-language and Indo-European is

solved by focusing on avalanches of ephemeral sound shifts instead of

considering genetic stability and structural typology. The white Caucasoid

race is an outgrowth of macrolithic hand-axe populations of tall

dolichocephals with vegetal subsistence and (pre)agricultural dispositions,

and its development competed with the Altaic races with flake-tool cultures.

These cultural traditions did not differentiate by unilinear monogenesis from

a common prehistoric unity but pursued independent growth by paragenesis in

several interfertile and interbreedable racial lineages. Their

archetypal differences were manifested by absolutely incompatible phonologies

and grammatical systems. African Negrids, Asiatic Caucasoids and European

Nordids applied cordal languages, whose consonantism was based on the

vibration of vocal cords and the opposition of voiced and surd phonemes

(Table 3). They pronounced vocalic cordal phonemes based on open syllables

and phonemes produced by airstream passing through vibrating vocal cords. If

there were any structural changes, they were caused by mixing with Altaic

agglutinating systems.

Table 3. The cordal

phonology of dolichocephals with macrolithic hand-axe industry Table 3 demonstrates an organic growth of

IE phonology from the Ursprache of Elamitoid Caucasoids and its

incompatibility with Germanic innovations hiding away Turanid origins. Table

4 attempts to reconstruct the steps that led to transformations of the earliest

Oldowan languages into Acheulean structure in grammar. It was a process of

changing Bantu language paradigms into the Caucasoid morphology and syntax.

It resulted from their clash with Asiatic flake-tool cultures with

agglutinating morphology. It implied turning African prefixing morphemes into

Asiatic suffixing constructions and reduced Bantu nominal classifiers to the

gender opposition of animate and inanimate nouns. Another result was the rise

of ergative constructions inherited from Tabunian Proto-Mousterians (Homo

heidelbergensis) settled in the Levant or the Arabian Peninsula. Elementary grammatical systems fall into

three types of nominal and verbal morphology. The gender-oriented morphology

is attributable to the language family of tall dolichocephals with hand-axe

industry and vegetal subsistence. In its original appearance documented in

African, Melanesian and Australian Negrids it partitioned nouns into classes

of animate, inanimate, vegetal and arboreal classes. These classed were

distinguished by prefixes put in front of nouns. In the Horn of Africa their

family ran upon Asiatic races with agglutinating language structures and

transitioned to suffixing morphology of inflecting type. The group of Asiatic

plant-gatherers, hoe-cultivators and agriculturalists reduced the system of

twelve nominal classifiers to the opposition of animate and inanimate nouns.

Their category included humans, animals, animistic spirits as well as sacral

deities.

Table 4. The nominal

morphology of dolichocephals with macrolithic hand-axe industry The chief representatives of Acheulean

languages were found in Anatolia, the Near East and Mideast. Their traces in

Asia Minor, Judea and Mesoponamia underwent assimilation, so their best

records have been preserved only in Georgian, Mingrelian, Persian and Burmese

languages. Another groups of survivals may be sought in Middle and New

Egyptian with w-plurals and in Ethiopian dialects. Their fates are

difficult to reconstruct but we may presuppose that there existed a strong

parallelism of development between Avestan and Sanskrit. Both dialectal

traditions were exposed to similar partners and absorbed their influences in

phonology as well as morphology. The categorisation in

Tables 3, 4 survived also in Anatolian tongues until their further expansion

in the Balkans encountered Gravettian tribes of Alpinids with sex-based

gender classifications. Their clash resulted in the rise of sex-based nominal

gender enriched by masculine o-stems and feminine a-stems. The

core of European languages accepted the dual opposition of masculine and

feminine gender. Yet some Iranian languages remained reluctant to their

addition and continued to adhere to nominal i-stems. Their subclasses

coexisted with Caucasoid vegetal u/w-stems that can be

explained as remains of Caucasoid b-plurals referring to agricultural crops

and instruments of farming activities. The classification of Indo-European

thematic and athematic stems may be regarded as a hold-over of ancient

invasions and infiltrations surviving in residual form in the territory of

Europe. The sex-based gender distinction of the suffixes -o and -a

first appeared in African Chadic and Ethiopian Galla languages and their

spread all over Europe was due to the Gravettian colonisation of short-sized

brachycephals to the north. They were embedded into the system of IE accidence

as new thematic stems distinguishing the masculine o-stems and

feminine a-stems. The u-stems penetrated into the IE word stock

with the propagation of Neolithic farming from the Fertile Crescent to the

Danubian river basin.

Table 5. Conservative

embeddings and regressive intrusions in Old Persian consonantism The first autochthons in

India were Negrids, whose word stock with prenasalised stops was absorbed

into Sanskrit by adding the prothetic vowel a-. As a result, the

initial phonemes /mb- nd- ŋg-/ were encapsulated into its norm as amb-, and- and ang-. After the arrival of black-skinned Negrids of Oldowan origin there

appeared a colonisation of Acheulean hand-axe cultures (800,000 BP) that

discarded prenasalisation and replaced the prefixing ba-plurals of

human beings with suffixal b-plurals as in Dravidian Gadaba and Gutob

in North Indian Punjab. In dialects of Central Asia they accompanied the

ethnonyms of Caspii and Lullubi. The first Indo-European

newcomers were Campignian Littoralists (10,000 BC) with cordmarked pottery,

who colonized the Vindhya Range in Gujarat. They were not populous enough to

Europeanise the entire Indian subcontinent but they disposed of an advanced

educated religious tradition that enabled their Brahman descendants to get

hold of an enviable scriptural monopoly. They managed to reinforce it as an

official administrative standard used in religious rites. Their integration

involved embedding the Brahmanic Proto-Gothic voiced plosives b, d,

g into the local phonological framework with murmured breathed stops bh-, dh-, gh-. Their heritage may be ascribed to Acheuloid racial groups with

Y-haplogroups G and H, whose occurrence culminates in the Indian

subcontinent. The Dravidian element in Old

Indian was represented by retroflex consonants written as ṭ, ḍ,

ṇ, ṣ, ẓ, ḷ, ɾ̣,

ɹ̣ but the IPA standard records them as /ʈ, ɖ , ɳ, ʂ, ʐ, ɭ, ɻ, ɽ/. They were notable for pronunciation with the tip of the tongue bent

backwards in a concave or curled shape. Their use was

obliterated in most language families but their remains often survive in the

affricates tr- dr-, tl- and dl-.

Most types of notation do not distinguish their apical and laminal

pronunciation. The laminal retroflex consonants were characteristic of

Tungusoid fishermen, who disseminated them in Eurasia with Aurignacian

colonisations around 40,000 BP. The apical or cacuminal retroflex consonants

must have been imported by Turcoid cultures with microlithic flake-tools

around 11,000 BC. These ethnic factions influenced also Iranian and Caucasian

languages but in less visible measure. (from Pavel Bělíček: The

Analytic Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, pp. 35-41) |

The Elamite and Caucasoid Languages with b-plurals Caucasoid languages do not

differ from Palaeo-Negroid languages only in age and dating, their principal

difference was one between a mixed heterogeneous system and a pure archetype.

They developed a new linguistic type of inflecting declensions and

conjugations because their grammatical morphemes lost their original

regularity and structural clarity by assimilation. Their inflecting paradigms

were hybrid structures mixed from Palaeo-Negroid prefixing languages and

Palaeo-Mongoloid suffixing agglutination. Some of their morphemes resulted

from transforming prefixes into suffixes and some were agglutinating suffixes

adopted from their northern neighbours. The inner Negroid substance was

preserved transparent as a substratum in the shape of a Mongoloid environment

in order to give birth to Caucasian and Indo-European irregular inflection.

This result of their symbiosis was as inorganic as is the white Caucasoid and

Nordic race. Both are two incongruous mixtures of black, yellow and dwarfish

people in different mutual rates. In spite of their secondary derived origin,

they formed compact contact unities owing to a long-term common

existence. In North Africa the element

of Palaeo-Negroid peasants and their prefixing classifiers is still dominant

but in the Near East and the Caucasus it was rather suppressed by Hamitoid

pastoralists and condemned’ to a subdominant position. Originally,

Palaeo-Negroids formed a continuous belt of plant-gathering populations

leading from the tropical forests of Africa to the tropical forests of

Austronesia. Later one stretch of this belt, centred in the Near East, formed

a bridge exposed to a long-term linguistic influence of Turkic, Uralic and

Altaic languages. As a result, there appeared a number of Hamitic, Semitic

and Caucasian dialects with different rates of their phonemic, grammatical

and lexical patterns. The most characteristic survival is a group of Lezghian

languages (Budukh, Botlix, Dargin, Godoberi) that have surprisingly preserved

Palaeo-Negroid phonemes, prefixing affixation, classifiers as well as subject

and object markers. This deep layer of Proto-Caucasian was

superimposed by Acheulian and Micoquian newcomers who started their travels

in North Africa and spread a new reformed standard as far as India, the Far

East and America. Caucasoid tribes remained inactive during the last Wurm

glaciation and were restored to life about 10,000 BC when they set out

as Basket-Makers to conquer America. Now it is amazing to compare Lezghian

languages as an archaic Eteo-Negroid survival with Georgian and Kartvelian

dialects that represent the reformed Caucasoid standard. Comparative linguistics

tends to subsume Caucasoid languages chiefly into two large families. The

first group are Semito-Hamitic languages (Cohen 1947; Diakonoff 1965)

that were renamed as Afroasiatic family thanks to the theoretical

initiative of J. H. Greenberg (1958, 1963a). The second group consists of a

few independent families in the Caucasus that A. Dirr (1928) called Caucasian

languages but Russian philology insists on applying the term of

‘Ibero-Caucasian languages’. These are divided into Kartvelian,

Abkhazo-Adygean, Dagestani and Nakh families (Deshiriyev 1978: 90) or into

Kartvelian, Abkhazo-Adygean, Avar-Andi-Cez, Lezghian, Dargino-Lak and

Bats-Chechen group (Jazyki narodov SSSR IV, 1967). The Kartvelian (Georgian, Mingrelian, Zan, Svan) and Abkhaz group

(Adygei, Abazin, Kabardin) are mostly found in Georgia, the Nakh group (Bats,

Ingush, Chechcn) and Dagestani languages are concentrated in the east

Caucasus. Such classifications of

Caucasian languages suffer much from imprecision because it is not based on

‘genetic kinship’ but on real grouping and ‘secondary contact unities’

(Palmaitis 1978). Two layers of their common dominant superstratum, which

cannot be mistaken for a common predecessor, are formed by b-languages

remarkable for the plural marker -b. Other subfamilies could be

classified as overlapping with Turkic, Bulgarian, Ossetic and Scythian

families and denoted as something like Turco-Caucasian. Instead of

introducing new tedious terms we had better use convenient working coinage

such r-Caucasian as an informal concept for all

Caucasian languages containing statistically relevant rates of Turcoid r-plurals.

Proto-Caucasian: Godoberi, Tindi, Bagvali, Dargin, Tsaxur, Bezhita,

Rutul, b-Caucasian: Georgian, Mingrelian, Lazi, Svan, Ginux, Gunzib, Xvarshi, r-Caucasian: Agul, Rutul, Tsaxur, Archi, Budux, Xinalug, Kryz l-Caucasian: Svan, Avar, Andi, Botlix, Axvax, Bezhita, Caucasoid b-languages

in Nigeria, Chad and Sudan cannot be divided into areal groups, either. Their

westernmost belt starts with the Fula or Western Atlantic subgroup

(Wolof, Serer, Fula), Hausa group (Hausa, Yoruba, Kotoko) and a Chadic

subfamily (Bolewa, Kotoko). The Coptic group includes (Middle Coptic,

Middle Egyptian) and some Cushitic languages (Sidomo, Iraqw). In the Near

East their stock was represented by Elamite that stands for related

dead languages of Kaspii, Gutii and Lullubei. In the

Caucasus their belt continued with b-Caucasian languages. Further travels

continued to the east and settled down in Tokharian remarkable for the plural

ending -wa (Poboźńiak 1985: 258.). Since the tongues of Harappa

civilisation have not been deciphered satisfactorily, their progeny must be

sought in most Indian and some Dravidian languages. In southern India the peasant

substratum with b-plurals is represented by the Kodagu subgroup

of Dravidians (Khonde, Kota, Kolami, Kodagu and Gadaba). Nobody can prove

that they are Acheulian autochthons who as far as the Movius Line in eastern

India where their eastward travels stopped (Feder, Park 1997: 255). More active that this

isolated archaic settlement was the group of Basket-Makers that

penetrated to the Amur and the Far East about 8,000 BC. The family of Palaeo-Siberian

languages with b-plurals includes Youkaghir, Aleutian and Koryak,

other kinsmen of this stock probably became extinct amidst the Ural-Altaic

element. The plurals in -vlak in Mari may document one isolated islet

and one possible travel route across Siberia. After passing the Bering Strait

basket-makers proceeded southward to the fertile lowland plains in the

southeast of North America but their mainstream headed for Mexico. The Siouan, Caddoan and Mayan families had

probably their starting-po Turkmenistan. The Tupí-Guaraní group, on the other

hand, seems to grow out from more ancient roots of Austronesian stamp. The Caucasoid Declension

Inflecting languages are considered as one of independent

linguistics types common in the European and Caucasian area (Skalička 1951;

Miłewski 1948). Typical inflecting systems may be studied in the

Indo-European family and the Kartvelian group. Inflection resembles

agglutination safe for a lack of clear etymology and structural regularity.

Whereas Ural-Altaic agglutinating suffixes may be joined arbitrarily and cumulated

mechanically to one another, every Indo-European and Caucasian inflecting

marker is a unique complex indecomposable unit without clear etymology. Owing

to a strong tendency to fuse morphemes into irreducible units, inflecting and

‘flectional’ languages are also classified as fusional, ‘amalgamating’

or ‘assimilating’ language structures (Axmatova 1966: 532, Erhart 1984).

The most remarkable manifestation of inflection are Indo-European

declensions considered as system of case paradigms divided according to

different stems, numbers and gender categories. The Caucasoid inflection may

be represented by Elamite that that has two gender categories (genus

personale for animate beings and genus materiale for inanimate

things). There are two numbers, singular and plural, no evidence of

duals was indicated. Singulars of animate nouns end in -k, their

plurals are remarkable for the ending -p that corresponds to the markers ua-,

ui- and pi- in Hattic. Inaminate nouns have a singular marker -r

and a plural ending -me which is often dropped. This state of nominal

categories is compatible with Hattic, Luvian and Hittite that display the

opposition of animate gender and genus commune for inanimate abstract

and material entities (Labat 1947, McAlpin 1974).

Less typical is the state in Hurrian, Urartean and Georgian. These

languages are Caucasoid in lexical substance but they lack nominal gender and

their case paradigms exhibit more agglutination than pure inflection (Klimov

1979: 115). The Geogian plural marker -eb, Elamite animate plurals in

-p and Hattic ua- and Aramaic -w demonstrate how the

Bantu animate plural prefix b/ba- turned into the Caucasian animate

suffix -p/b. Under the influence of the suffixing Asiatic languages

Caucasoid dialects abandoned prefixing morphology and shifted the

classificatory prefixes to the end of the word. The original prefixed plural

markers were preserved in Hattic pi-, Gunzib b- or Hokan ba-.

In other languages they were shifted to the word-final position and appended

to the root as inflecting suffixes.

On the Caucasian crossroad of prehistoric civilisations the

Palaeo-Negroid nominative construction clashed with the Palaeo-Mongoloid

accusative construction to give birth to the Caucasian ergative

construction. Caucasoid morphology developed from Palaeo-Negroid

classifiers by several fundamental overturns. The most important step

consisted in abandoning Palaeo-Negroid object markers and verbal infixes that

were replaced by case endings attached to nouns. Caucasian case systems and

European declensions originated by dissociating verbal affixes from verbs and

attaching them to nouns in objects following the verb. So the Bantu causative

verbal infix -s- probably turned into the ergative case s-ending

in Caucasoid languages and the Bantu plural marker b- became the

ending of the Caucasian absolutive case. In European languages, where the accusative

construction won owing to Mesolithic hunters of Asiatic origin, this

transformation proceeded in a different way. The Negroid causative infix -s-

became the ending of plural nominatives and the marker -b- began to

refer to plural datives.

There were several groups of languages involved in the ‘ergative

revolution’. Ergativity became very common in the Hamitic, Abxaz and Scythian

family of megalithic cultures though their southernmost archaic promontories

in South Africa (Hottentot Nama, Masai) have an accusative construction.

These pastoralist cultures were intertwined with colonies Caucasian peasants

who acquired the ergative construction by copying Hamitic syntax.

Indo-European languages either escaped ergative constructions or disentangled

their remains by adapting them to Asiatic accusative syntax (Schmalstieg

1980, 1985). (from Pavel Bělíček: Prehistoric Dialects I, Prague 20014, pp. 206-208, 219-220) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||