|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

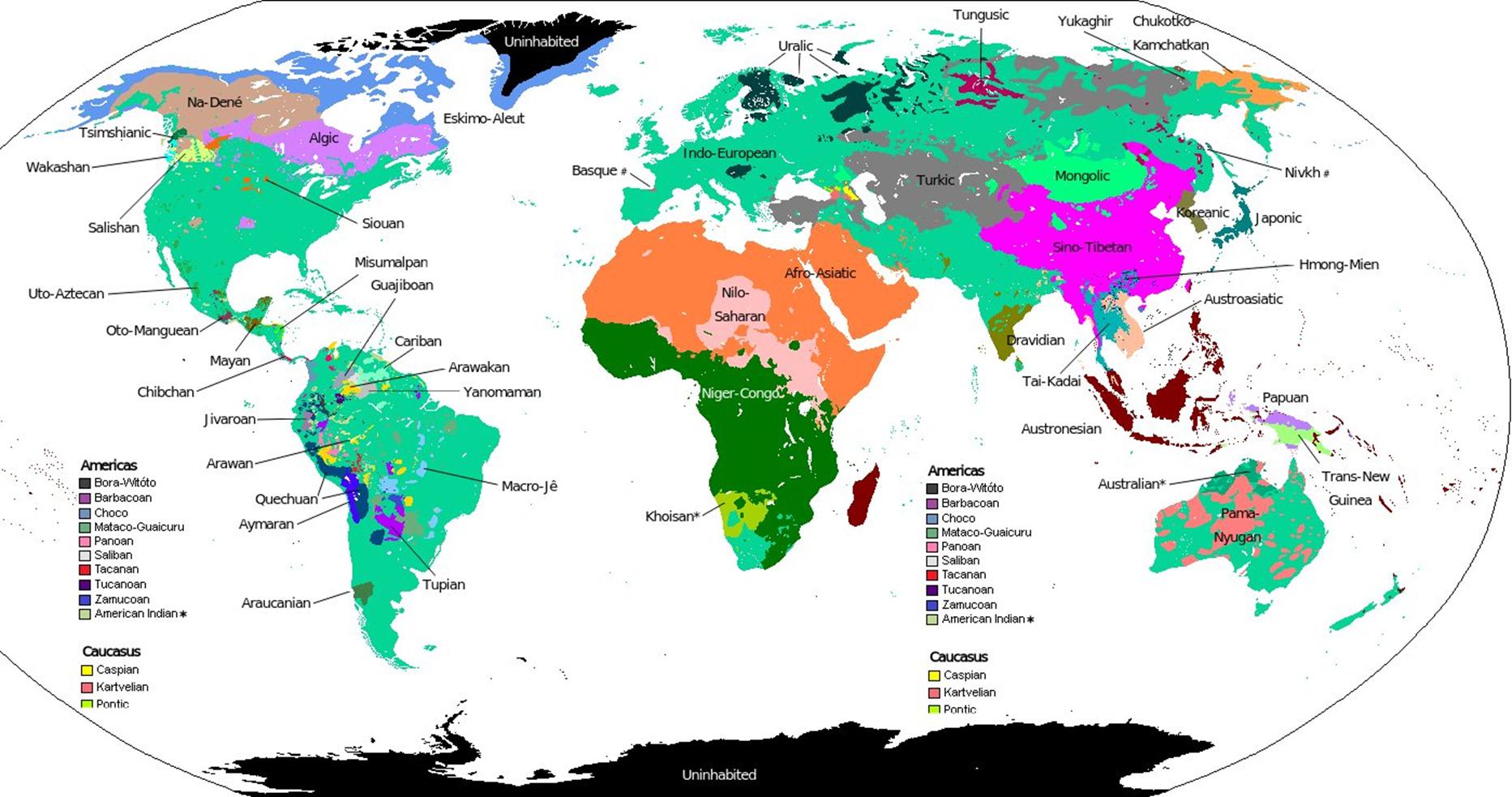

The Proto-Languages of Families Reinterpreted as

Heterogenous National Administrative Domains Clickable terms are red on the yellow background |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Table 1. Worldwide Human Language Families |

||||||||||

Table 2. The Syncretic Domains of Traditional Language

Families |

||||||||||

|

Hypothetical Language

Families Decomposed into Palaeolithic Tribal Dialects Practically all

proto-languages, common languages and their language families rely on several unconfirmed and uncertified

presuppositions of ‘prehistoric unitarianism’. They believe that human

cultures and languages originated by a sort of self-fertilising autogenesis

enabling a procreation of a single ancestral Adam, who spread one

proto-language, populated some vast area and

filled it with his family offspring. Every continent, country and region had

one unique progenitor, spoke one pure father tongue and grew into an entire

nation. In the Bronze Age human populations of entire

The following reclassification of traditional languages warns that

they represent cumulative sums of heterogeneous contact neighbourhoods and

have to be decomposed into elementary atoms of palaeolithic

tribal dialects. Its subcategorisation applies various types of pluralisation

with plural x-suffixes: l-dialects: Epi-Aurignacian Leptolithic lakelanders

of Tungids with pulmonal fortis/lenis correlations, laminal retroflexed

consonantism, vocalic synharmony, agglutinating morphology, l-plurals and SOV word order. r-dialects: Epi-Magdalenian and Magdalenian Microlithic

cliff-dwellers of Cimbrids with pulmonal fortis/lenis correlations,

apical/cacuminal retroflexed consonantism, vocalic synharmony, agglutinating

morphology, t-preterits, r-plurals and SOV word order. n/k-dialects:

Epi-Megalithic cultures of pastoralist highlanders of Abasgo-Scythoids with

glottalic ejective/implosive consonantism, reduced vocalic repertory, incorporating

morphology, n/k-plurals and OVS word order. t-dialects: Epi-Solutrean cultures of pastoralist

steppe grasslanders of Sarmato-Sumeroids with glottalic ejective/implosive

consonantism, agglutinating morphology, analytic verbal predication, reduced

vocalic repertory, collective t-plurals

and SOV word order. b-dialects: Epi-Yabroudian cultures of oriental

agricultural Elamo-Hittitoids with flat-roofed labyrinths, tell-sites, voiced-voiceless cordal consonantism,

rich quantitative vocalism, b-plurals

and SVO word order. s-dialects: Epi-Micoquian cultures of western

agricultural Getids with longhouses in alluvial valleys, voiced-voiceless

cordal consonantism, rich quantitative vocalism, s-plurals and SVO word order. i/e-dialects:

Epi-Gravettian cultures of short-sized Lappids/Alpinids with semidugouts and

lean-tos in forest thickets, palatal lingual consonantism, rich quantitative vocalism,

nasal vowels, tonality, i/e-plurals, reduplicative

pluralisation, isolating morphology and SVO word order.

Such x-dialects

dissect mixed modern living languages into typologically consistent

subphonologies, subvocalism, subconsonantisms, submorphologies and

sublexicons. |

Indo-European Projections of

Language Hyperfamilies

The reformed discretive taxonomy of languages families assumes that

most post-eneolithic language group are hybrid cumulative amalgams of

heterogeneous ethnic components and ought to be distilled into genuine

eteo- languages such as Eteo-Cretic

and Eteo-Cypriotic (from Greek eteos

‘genuine, pure’). The principal task of comparative linguistics and ethnology

is to atomise current cumulative proto-languages and mixed languages families

into eteo-dialects of Palaeolithic tribal tongues. After their subtle

differentiation it will be possible to link them into long chains of

prehistoric migrations and reconstruct their supracontinental hyperfamilies.

These methods will make it possible to unite isolated eteo-languages

(Noricum, Celticum, Slavicum) into supranational unities such as

Pan-Scythicum, Pan-Sarmaticum, Pan-Cimbricum, and Pan-Geticum). The best

illustration of cumulative amalgamation in post-eneolithic societies is

provided by the study of lexical word stock and different ‘sublexicons’ in

current mother tongues. The seemingly extinct tribes survive in the

traditional Indo-European nominal stems (o-stems, a-stems, i-stems,

u-stems, t-stems, r-stems and n-stems) and shine

translucently in numerous grammatical exceptions. What looks like a lawful

category of archaic Indo-European heritage are mostly individual exceptions

and residual remains of double plurals immersed into a common language

together with original alien plural suffixes. Anomalous

nominal stems appear as products of different tribal cultures and

professional castes in prehistoric civilisations. They elucidate how mixed

post-eneolithic societies composed from incompatible incompatible layers.

Most of them integrate heterogenous admixtures of rural agricultural

lowlanders with dolichocephalous physiognomy, short-sized suburbans of

brachycephalous phenotype, big-game hunters remarkable for tall-sized

brachycephalous features and piscatory wetlanders with flat faces and protruding

cheekbones: a. the most populous class of Indo-European autochthons encompasses occidental agricultural lowlanders with s-plurals

and animate or inanimate i-stems, b. their oriental brothers were Anatolian

farmers, who imported u-stems derived from original b-plurals, c. big-game hunters descended from boreal

steppe grasslanders with kurgan burials and imported Scythian n-plurals, d. the plural suffix -n probably stemmed

from k-plurals and transitional nk-plurals; k-plurals

were common among Bascoid megalith-builders, Caucasian Abasgoid kurgan

builders and pastoralist highlanders, who intruded into the IndoEuropean area

from without, e. their brotherly Uralic tribes originated

from horse-flesh eaters (hippophagi) and contributed by collective t-plurals, f.

their common home was in Palaeo-Siberian languages

with collective t-plurals and distinctive k-plurals, g. Neolithic fishermen composed from

Palaeolithic lakeside wetlanders and seaside waterlanders remarkable for

retroflexed consonants, h. Epi-Aurignacian tribes colonised wetland

areas located below sea level, specialised as lakelanders, inhabited lakeside

stilt-dwellings or pole-dwellings and used original Tungusoid l-plurals,

i. their affiliated outgrowth consisted from

Turcoid tribes, who were responsible for spreading Magdalenian and

Maglemosian Microlitic cultures; they imported r-plural

and applied consonantisms with apical retroflexed plosives, j. populous incomers

included Epi-Gravetttian Lappids with masculine o-stems with i-plurals

and feminine a-stems with e-plurals that stemmed from North

African Alpinoids (Hausa, Joruba, Vandala, Boleva). |

|||||||||

|

INDO-EUROPEAN DOMAIN GERMANS ® r-Germans + s-Goths + k-Scandinavians.

k-Scandinavians ® Scots,

Scandinavians, Sudini, Sudeten

Germans + Varyagi. r-Germans ® Hermunduri, Irminiones + Teutones + Cimbri, Ambrones + Thuringi + Vikings. s-Goths ® Goths + Frisians + Angles +

Saxons; Langobards + Burgundians + Rugians; Swabians + Franks + Senons. CELTS ® i-Gauls + r-Cimbri + s-Britons + l-Belgae + t-Volcae. i-Gauls ® Celts, Gaels + Albanians + Veneti, Gwynt, Goidel, Gwynned. l-Belgae ® Belgae, Firbolg + Daanu + Picti? +

Cornish, Cornubii? t-Volcae ® Welsh, Volcae Tectosages + Morini

(Myrsingen) + Ossi. r-Cimbri ® Cymri, Cambria-Cumber, Iberi, Hiberni, Ombrones, Eburones. ROMANCE ® s-Italians + r-Umbrians

+ t-Oscans + l-Apulians + i-Gauls. s-Italians ® Italiotes + Bruttii. l-Apulians ® Apuli,

Paeligni + Daunii +

Sardi + Latini + Piceni. r-Umbrians ® Umbri,

Cimbri + Taurini,

Tyrhenes, Etruscans + Siculi,

Sicani. t-Oscans ® Osci, Ausoni + Volsci,

Veleiates + Boii + Marsi, Marsigni, Marrucini, Marici + Sabini,

Samnites. i-Gauls ® Veneti

+ Albanenses +

populi galloitalici. GREEKS ® k-Cyclopes + i-Hellenes

+ r-Dorians + l-Pelasgians. l-Pelasgians ® Paeones, Pelasgiotes + Danaides + Karoi + Leleges. r-Dorians ® Doroi, Tauroi + Kimmerioi + Greeks, Geryones. k-Cyclopes ® Thracians + Bessoi, Mysioi, Mosxoi. i-Hellenes ® Galatians, Hellenes + Ionoi (< *Jav/Alban) + Aetolians (< *Ant). BALTS ® s-Prussians + i-Lapps + t-Uralians + k-Scythians.

s-Prussians ® Borussi, Prutenes +

Jaćwings, Jotija. t-Uralians ® Estonians, Aesti, Eeste + Veltai + Lithuanians, Latvians, Letgala,

Lettia + Mera, Muromi. i-Lapps ® Laplanders (< elves) + Finns (< Wends) + Galinda, Semigala. k-Scythians ® Scandinavians, Sudavi, Sudini,

Tchud’ + Vesi, Vepsa + Varyags. SLAVS ® s-Prussians + i-Polabane

+ t-Russians + k-Ukrane + l-Polane + r-Silesians. i-Gravettian

Palaeo-Slavonians ® Slavs + Sorbs/Sorbians + Slovaks + Slovenes. i-Lusatian Neo-Slavonians ® Holasici + Koledici+ + Polabans + Croatians + Czech + Lechites +

Mechites. i-Polabane (< elves) + Wends + Antes + Vyatichi. k-Ukrainians/Ukrane (< Ugrids) + Magna Scythia, Scythia Minor + Mazuri +Masovians/Mazowsze + Varangians/Varyagi (< Ugrids) + Buzhans + Pshovane/Pšovane. s-Prussians ® Borussi, Prutenes +

Jaćwings, Jotija + Chutici (< Goths), Ulichi (< Uglichi, Angl-). t-Russians (< Erzya,

Aorsi, Roxolani) + Ross’ + Carpathian Rusyns. t-Rusyns

+ Moravians/Moravane/Merehani

+ Wallachians (< Volcae) + Veleti + Boihemi. l-Bulgars ® Polyane + Polotses + Polane + Volha Bulgars + Belarusians + Luitizes +

Lendians (< Lędane). r-Cossacks (< Kazakhs) + Silesians/Slezans

+ Kaszubians + Tverians + Yam/Hamme (< Huns). IRANIANS ® n-Scythian + t-Sarmatian + i-Kafir. n-Scythian ® Persian, Talysh, Tat, Gilaki, Semnani, Sogida, Pashto, Kurmanji,

Mazanderani, Mukri, Khowar. t-Sarmatian ® Ossetic, Yaghnobi, Ishkashmi, Yazghulami. i-Kafir ® Kashmiri, Waigali, Kati, Ashkun. INDIANS ® s-Indian + i-Indian + r-Indian + l-Dravidian

+ r-Munda + t-Aryan. s-Indian (Vindhyas cord-impressed ware, 10,000BC) ®

Getae + Brahmans + Kshatriya. i-Indian (Buddhist

cremating incinerators, H-cemetery 1800 BC ) ® Hindi, Kashmiri, Malayam, Telugu. r-Dravidian (Turcoid Shivaists) ® Tamil, Tulu, Malayam, Kurukh, Gadaba, Parji, Kolami, Naiki, Kannada, Konda,

Kodagu. l-Dravidian (Tungoids) ® Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Kolami,

Purji, Gadaba. b-Dravidian

(agriculturalists) ® Kodagu, Kolami, Gadaba, Purji. k-Dravidian ® Kui, Naiki, Tamil, Gondi, Braui, Kuvi. t-Aryan (Sarmatic

raiders, iron metallurgy) ® Aryas, Ashuras, Assamese, Moran, Hmar. t-Myanmar (Sarmatic

raiders, iron metallurgy, Myanmar 600 BC) ®

Mru, Rohingya, Asli. |

NOSTRATIC DOMAIN DRAVIDIANS ® s-Indian + i-Indian + r-Indian + l-Dravidian

+ r-Munda. r-Indian ® Nepal, Assam, Oriya, Benghali. r-Dravidian ® Tamil, Tulu, Malayam, Kurukh, Gadaba, Parji, Kolami, Naiki, Kannada,

Konda, Kodagu. l-Dravidian ® Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Kolami,

Purji, Gadaba. i-Indian ® Kashmiri, Malayam, Telugu. b-Dravidian ® Kodagu, Kolami, Gadaba, Purji. k-Dravidian ® Kui, Naiki, Tamil, Gondi, Braui, Kuvi. CAUCASIANS ® b-Caucasians + l-Caucasians + r-Caucasians. r-Caucasian ® Agul, Rutul, Tsaxur, Archi, Budux, Xinalug, Kryz. s-Caucasians ® Bats, Ingush, Chechen. l-Caucasian ® Urartian, Svan, Avar, Andi, Botlix, Axvax, Bezhita, Bagvali, Tindi, Chamalal. b-Caucasian ® Georgian, Mingrelian, Lazi, Svan, Ginux, Godoberi, Lezghian, Tindi, Bagvali, Dargin, Kapucha, Tsaxur,

Karat, Dido, Gunzib, Xvarshi, Cez, Bezhita, Rutul, Kryz. URALIANS ® k-Ugric + t-Uralian + i-Saamic + s-Perm. k-Ugric ® Vepsa (Vesi), Varyags,

Magyars, Xanty, Mansi. t-Uralian ® Finnish, Estonian, Mordvin. Ostyaks, Meru. l-Bulgarian ® Upper Mari, Lower Mari, Karelian, Bashkir, Volga Bulgars. i- Saamic ® Lappish, Samoyedic, Selkup, Nenets, Enets. s-Permian ® Komi, Perm (< Barmia), Udmurt. TUNGUSIANS ® l-Tungic

+ t-Sibiric + s-Khitan Getic + r-Yakut + n/k-Ugric + Chukchi. l-Tungic

(Eteo-Tungids) ® Evenki (-l, -sal), Negidal, Even, Udegei, Birar. n/k-Ugric (Kerek-Ugrids, from Ugr-) ® Orok, Oroch, Orochon-Oroqen. k-Tungids(?) ® Udegei (-xal), Manchu (-xon), x-plurals may be

derived from the suffix -sal. t-Sibiric (Uraloid

Sibirids) ® Manchu (-ta), Eskimo (collective plural in -t). t-Sibiric (Uraloid

Sibirids) ® Manchu (-ta), Eskimo (collective plural in -t). s-Khitan Tungic ® Evenki (-sal),

Nanai (-sel), Udegei (-l, -xal),

Manchu (-sa, -se, -si, -so). s-Khitan Getic

(Cord-Impressed Ware, Jōmon Nordids) ® Manchu (-se) r-Yakut

Turanic ® Yakut (-lar), Manchu (-ri), Barguzin Tungus

(-war). b-Tungids ® Barguzin Tungus

(-war), Koryak (-wwi), Aleutian (-wwi), x-Sinitic

® Chukchi, Evenki, Even and Athapascan Na Dene display

reduplicated plurals that betray origin from Sinids. TURKIC ® r-Turkic

+ l-Tungic + t-Uralo-Sibiric + s-Khitan Getic + n/k-Ugric. (The Yamnaya culture with Tungic

l-plurals was overlaid by the Catacomb culture with Turanic r-plurals

and their overlapping gave rise to the agglutinative double plurals with -lar). lar-Turkic ® Oghuz Turks,

Turkish (-ler, -lar), Azerbaijani (-lar, -lər). l-Tungic

(Eteo-Tungids) ® Polovtsy,

Plavtsy, Balkars. n/k-Ugric

(Kerek-Ugrids) ®Turkic (-n, -an). t-Sibiric (Uraloid

Sibirids) ® Turkish (-t, -an). s-Getids

(Corded-Impressed Ware, Baikal Nordids) ® Turkic (-z), Yakut (-čït, -sït), Kirghiz (-z). (Kitoi and Afanasievo cultures near Baikal Lake created crossbreds of

Turanids with Getids). MONGOLIANS ® t/d-Mongolic + + t-Sibiric + l-Tungic + s-Khitan

Getic + r-Yakut + n/k-Ugric. t/d-plurals ® Mongolic (-d, -ud, -γud,

-nuγud), Literary Mongolic (-nar, -s, -d,

-ud), Buriat (-t, -D). d-Mongolic ® Ordos/Urdus (-d > -D or -t). l-Tungic

(Eteo-Tungids) ® Mongol (-l, -tšūl, -čūl). n/k-Ugric

(Koryak-Ugrids) ® Mongolian (-n, -nar, -nad,

-nuγud), written Mongolic

(-nar), Khalkha (-ner). t-Sibiric (Uraloid

Sibirids) ® Turkish (-t, -γut). s-Khitan Getids

(Corded Ware Nordids) ® Mongolic (-s, -us, -čud, -tšūl < -šūl), Literary Mongolic (-s), Ordos (-s, -ūs), Khalkha (-s), Kalmyk

(-s), Moguor (-s, -sGi), Chuvash (-sɛm,

-sayun), Mogol (-s > -z), Alar Buriats (-šūl, -tšūl). r-Yakut ® Khalkha (-ner),

Yakut (-lar). |

|||||||||

|

Table 2. The Phylogenetic Taxonomy of Discretive

Substratum Subfamilies |

||||||||||

|

Syncretic Natiography vs. Discretive Substratum

Taxonomy in Prehistoric Studies Classic prehistoric studies have built an

all-embracing syncretic nomenclature of language families based on recent

contact mixtures in concentric neighbourhoods and administrative domains. Its

tenets cherish several fallacious Linnéan preconceptions misleading to inacceptable

conclusions. They believe that human phenotypes originated as a result of

short-term climatic adaptations and every continent was populated by a race

of white, black, brown, yellow or red people (C. Linné 1756). August

Schleicher (1961-62) assumed that every race had spoken a different common

mother tongue and elucidated how Nordic Indo-Europeans split into modern

families of national languages. His Stammbaumtheorie, J. Schmidt’s Wellentheorie

(1872) and O. Höfler’s Entfaltungstheorie

(1955, 30–66) devised models of divergent monogenism explaining

the genesis of European families from a common proto-language. They

reconstructed hypothetical Ursprachen that neglected incongruent heterogeneous components and did not realise ‘the mixed

character of all languages’ (Baudouin de Courtenay 1901). Such omissions

resorted to methods of syncretic cumulativism that mixed incompatible

admixtures into artificial unities boiling in one melting pot. A curative antidote to syncretic

cumulativism was discovered in approaches of discretic decomposition that

poised rough synthetic cumulation with procedures of subtle analytic

substratic disassembly. New diffusionist trends of the 20th century

admitted processes of convergent acculturation and diverted attention from schematic

genealogies to cultural typology of indigenous civilisations. Fritz

Graebner’s diffusionism (1911) turned focus to migrations of ethnic Kulturkreise that diffused over large areas of the

world. Leo Frobenius (1933) discovered surprising transcontinental

parallels between African, Indian, Siberian and Southeast Asiatic typological

paradigms. Nikolai Trubetzkoy (1939) and Heinrich Wagner (1970) developed a

new model of ‘chain theory’ (Kettentheorie) that traced typological

congruencies in different families along lengthy migration corridors. A

similar theoretical campaign was launched by Vittorio Pisani’s Neolinguistics

(1957) and Mario Alinei’s Palaeolithic Survival Paradigm (1996). They refuted

preconceptions of Common Celtic and Common Italic that united different

ethnic groups in spite of their genetic and cultural incompatibility. Their

arguments are supported also by Transparenztheorie (Bělíček 2004, 2018) emphasising

that relevant residues of Palaeolithic dialects shine through modern national

tongues. Most terms of prehistoric disciplines are

mixed syncretic categories because their evidence is based on late

postdiluvian or post-eneolithic archaeological cultures composed from

heterogeneous substrates and ethnic castes. Most archaeological

technocomplexes and languages families are mixed concoctions of diverse

ante-eneolithic remnants. They do not meet requirements of systematic taxonomy

and may be arranged only in enumerative catalogues of items. Their assortment

tackles the inconveniences of primeval alchemy that worked with mixed

substances such as clay, mud and dirt. They lack homogeneous consistence and

have to be analysed into atoms of discrete elements. Their hypothetical

reconstructions of proto-languages have to be broken into heterogeneous

subgrammars before they may be composed into molecules of consistent and

congruent macrofamilies. Syncretic cumulativism confuses prehistoric

ethnic groups with medieval principalities and their incoherent multiethnic

administrative domains. It does not pursue the natural course of real

progressive evolution and proceeds in regressive counter-clockwise direction

from the recent present to the remote past. Its reconstructions start from a

modern written national language (New English), derive it from late and early

medieval predecessors (Middle English, Old English) and end with

reconstructing a hypothetical eneolithic subcontinental generalisation (Common Germanic, Proto-Germanic). The latter are grouped

into large cultural empires of continental macrofamilies such as

Indo-European. Such a readymade template was slavishly applied also to

families of Asiatic, African, American, Australian and Oceanic world’s ends.

Its chief fallacy consists in relying exclusively on sovereign’s written

literary records and neglecting hundred thousand years of tribal oral

dialects. It leads to overrating recent national languages and entrusts them

with an undue monopoly in identifying ethnicity. It misinterprets mixed

nations as pure ancient tribes and creates false language unities that are

thoughtlessly transplanted into other prehistoric disciplines. Such

misleading subcategorisation necessarily misguides them to a terminological

deadlock. References Alinei, Mario. 1996. La teoria della

continuità. Bologna: Mulino. Ascoli, Graziadio di. 1861. The First Letter to Francesco D’Ovidio. Rivista

di filologia e d’istruzione classica, 10, 1881—1882, 1-71. Baudouin de Courtenay, J. 1901.

O

smeshannom kharaktere vsekh yazykov. Zhurnal Ministerstva narodnogo

prosveshcheniya, no. 337, 1901, 362-372; On the Mixed Character of All Languages [1901], in: A Baudouin de

Courtenay Anthology. The Beginnings of Structural Linguistics. Bloomington -London 1972, 216-226. Bochkovsky, Olgerd. 1927. Natiology and Natiography. Prague. Bochkovsky, Olgerd. 1934. Foreword to Natiology. Prague. Bombard,

Allan R. Toward

Proto-Nostratic: A New Approach to the Comparison of Proto- Indo-European and Proto-Afroasiatic. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1984. Bombard,

Allan R. 2011. The Nostratic

Hypothesis in 2011: Trends and Issues. Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man. Dilthey, Wilhelm. 1883. Einleitung in die Geisteswissenschaften,

Leipzig : Duncker & Humblot. Gimbutas, Marija. 1956. The Prehistory of

Eastern Europe. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum. Graebner, Fritz. 1911. Die Methode der Ethnologie.

Heidelberg. Haeckel, Ernst. 1866. Generelle

Morphologie der Organismen. Berlin : G. Reimer. Haeckel, Ernst. 1877. Anthropogenie: oder, Entwickelungsgeschichte des

Menschen. Keimes- und Stammesgeschichte.

Vol. 1. Leibzig : Engelmann. Höfler, O. 1955.

Stammbaumtheorie, Wellentheorie, Entfaltungstheorie 1. Beiträge zur

Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur 77,

30–66. Linné, C. 1758. Systema Naturae per regna tria

naturae. 10 Ed. 1 Holmiae. Mendeleev, Dmitri. 1868.

Основы

химии. Osnovy khimii. Moskva. Paul Reinecke: Zur Chronologie der 2. Hälfte des Bronzealters

in Süd- und Norddeutschland. Korrespondenzbl. d. Deutsch. Ges. f. Anthr.,

Ethn. u. Urgesch. 33, 1902, 17–22. 27–32. Reinecke, Paul (1965). Mainzer

Aufsätze zur Chronologie der Bronze- und Eisenzeit (in German). Bonn: Habelt. Schleicher, August. 1861/62. Compendium der

vergleichenden Grammatik der

indogermanischen Sprachen. (2 vols.)

Weimar, H. Boehlau (1861/62) Johannes Schmidt. 1872. Die Verwandtschaftsverhältnisse der

indogermanischen Sprachen. Weimar :

H. Böhlau. Trubetzkoy, Nicolai S. 1939. Gedanken über das Indogermanenproblem. Acta linguistica 1,

81-89, p. 82. Wagner, H. 1970. The origin of

the Celts in the light of linguistic geography. Trans. Phil. Soc.

1969, 1, 203-250, p. 228-9. Samuels,

L. K. Souzdaltsev, Igor. 1999. Natiology : social science for the third

millennium Englewood Cliffs, NJ : R & R Writers/Agents, ©1999. Wagner, Heinrich. 1970. The origin of

the Celts in the light of linguistic geography.

Trans. Phil. Soc. 1969, 1, 1970: 203–250. Windelband, Wilhelm 1894: “Geschichte und Naturwissenschaft”,

reprinted in his Präludien, vol. 2, pp.

136–160. Translated as “History and Natural Science”, by Guy Oakes, in NKR:

287–298. |

The Deadly Sins of Dogmatic Comparative

Linguistics The greatest hindrances hampering

progress in comparative linguistics and ethnology consist in the following

unpremeditated dogmatic preconceptions or inglorious ‘deadly sins’ (peccata

mortalia): (1) preferring the testimony of written inscriptions to oral

dialects and (2) regarding dialects as newborn daughters of the medieval

royal national standard; (3) inventing an artificial family and common

proto-language for every two neighbouring and overlapping national standards

sharing similar loanwords; (4) excogitating a vast indiscriminate language

unity for every subcontinent and world’s end; (5) neglecting antediluvian

prehistory as extinct and starting evolution from postdiluvian mixed

civilisations; (6) exterminating the Palaeolithic past as ‘a dead story’ and

mistaking eneolithic civilisations for tribal prehistory; (7) blending recent

heterogeneous ethnic mixtures instead of analysing them into elementary atoms

of pure Palaeolithic tribes; (8) deriving ethnic identity from final

geographic destinations instead of searching for original homelands; (9)

mistaking vicinal permeation and intertwinement for cognate genetic

affiliation, (10) studying sound shifts as phantoms without regard to

underlying live tribal bearers; (11) treating cultures as nameless spiritual chimaeras

detached from their material ethnic movers; (12) refuting principles of

‘linguistic materialism’ by dissevering language changes from underlying

ethnic and social reshufflings; (13) constructing humanities as

monodisciplinary chimaerologies where all terms are isolated solitaires

incompatible with taxa in their superordinated portative scientific fields;

(14) wasting too much time by focusing on isolated hybrids instead of

decomposing them into original primordial components; (15) building ethnology

and humanities on a rotten basis of breeding hybridology because missing

phylogenetic categories are made up for by ad hoc mongrel groupings, (16) disconnecting ancient tribal chains into isolated

unrelated phenotypes and filling their contact unities with heaps of

incompatible rubbish; (17) fabricating false recent national mixtures into

fictitious incongruous macrofamilies and pretending that they are primeval

proto-languages; (18) refuting attempts at an

all-embracing linguistic typology and ethnic characterology; (19) neglecting

the need to coordinate the multidisciplinary systematic taxonomy that links evolutionary glottogenesis with prehistoric

migrations and Palaeolithic typological archetypes; (20) yielding to periodic

returns of idealistic scholasticism in modern and postmodern prehistoric

studies and reducing them to a slavish description of isolated idiographic, person-oriented and subject-specific

phenomena (Windelband 1894: 150, Dilthey 1883). Idiographic preconceptions exert a

detrimental effect on all humanities since they dissolve lawful evolutionary

processes into unrelated sherds of chaotic factography. What now pretends to

be a systematic prehistoric ethnology is actually only a civilised historical

natiology (Souzdaltsev 1999) or natiography (Bochkovsky

1927, 1934). What puts on the appearance of

prehistoric studies is de facto only modern human geography and

political topography (Landesbeschreibung). It replaces valuable

prehistoric knowledge by Sunday school stuff training little children in

homeland study (Vaterlandskunde). It impermissibly omits prehistoric spoken tribal

languages and reduces them to late outgrowths of written national mother

tongues. As a result, comparative historical grammar discards

prehistoric oral dialects and starts its theoretical accounts from written

inscriptions on monuments. Such an inadmissible vivisection prevails in all

social and cultural studies. Literary theory omits prehistoric oral tradition

and starts with written literary history. Religionistics

starts with medieval syncretic religions without realising that they were

composed from aboriginal magic cults. Philosophy is no more aware of

its roots in proverbial sayings of magic folklore and begins with juristic sophistry. Modern historiography buries

prehistoric myths and legends as unscientific excogitations and acknowledges

only the testimony of written chronicles. These disciplines cannot establish

their systematic taxonomy since they speculate only on last few centuries and

bury several

hundred thousand years of Palaeolithic origins as extinct. This is why humanities deserve a

fundamental reform of their weak foundations and a radical amendment of their

anomalous malformations. They primarily need revisiting chaotic ad hoc terms

for isolated local phenomena, distil them into elementary atoms and recast

them into valid categories of systematic categorisation. The first step is to

devise a tenable systematics of disciplinary ‘pre-sciences’ that can classify

stages of evolutionary typology and elucidate archetype predecessors of

cultural genres. The concept of pre-science is derived from Latin praescientia and means oral ‘fore-knowledge’ in the early puerile stage of

indigenous communities. Current humanities distinguish only applied,

descriptive and summative research (-graphy, -logy) but rarely classify prescientific oral ‘fore-sciences’

(-genies), typological

classificatory ‘para-sciences’ and systematic nomothetic

‘pan-sciences’ (-nomies) in (Table

1). Such proposals develop Ernest Haeckel’s ‘recapitulation laws’ proclaiming

that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny and contemporary classificatory

phylology maps pathways of prehistoric phylogenesis (Haeckel 1866, 1877). |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||