|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

Baltic Tribal Groups Click on names (red letters) of human varieties (with yellow background) and read about their

decomposition into ethnic subgroups. Notice traditional fallacies and preconceptions concerning the traditional misleading categories of human races. Clickable terms are red on yellow background. |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

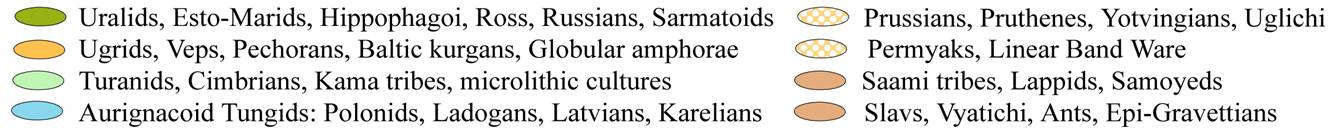

Baltic tribes in medieval and modern ethnonymy (from P. Bělíček: The Analytic Survey of European

Anthropology, 2018, p. 160) |

||||

|

|

The

Componential Analysis of Baltic Tribes

The earliest autochthons of Baltic

countries were the Balts, who belonged to Aurignacian populations of nomadic fishers. They did not

wander right from their Pontic starting-point north

of the Balto-Gothids: the dominant stock of the Gotho-Frisian Corded Ware culture (2900 BC) and its pignian

predecessors (10,000 BC); they moved eastward as Yotvingo-Prussians

and made battle- axes and boat-axes, Baltic racial

phenotypes derived from Nordic tall dolichocephals

mixed with Slavic and Saamic

brachycephals; heathen Prussians

lived in two-caste systems like Brahmans and Khattryias, they derived their origin from two brothers, the king Vaidevutis and the archpriest Bruteno. Prussians → Prussians (Latin

Pruteni), Bartians, Warmians/Varmians, Yotvingians (Latvian

Jātvingi, Polish Jaćwingowie, from Goths), (Samo)gitians/Zhemaitish

(from Goths), Sasnans. Baltids (Balto-Tungids): the second dominant of Aurignacian lacustrine fishers

and lake-dwellers in the Karelian lake

district, artificial islands on lakes, post-dwellings and above-water lake

houses, tepee huts of lavvu type, steep A-shaped houses, whose

gables had tepee-like crossed beams. Balts (Lithuanian

Baltai, Latvian Balti,

balt- means ‘white’ or ‘marshland’) → Karelians/Karjala,

Curonians, Lithuanians/Lietuviu, Latvians,

Latgalians, Ladogans. Balto-Lappids: Gravettian origins, cremation burials, yodelling, melodic

tones, abundant palatals and sibilant

affricates and diphthongs, satemisation, fronting

round and back vowels). Lappids →

Galindians/Goliadj, Semigallians (from Saamis +

Gallians), Samogitians

(from Saamis + Goths), Sambians (from Balto-Scythids (Ugro-Scythoid tribes of tall brachycephalous

kurgan-builders, mounds of cupolar and domed shapes, convex noses, often light

reddish skin and red hair) →

Chud’, Varangians,

Vod’/Votes, Ingrians/Izhorians, Veps, Sudovians (from Scyth-), Węgorzewo-Mazowsze. Balto-Uralids (the Pit-Comb

Ware culture 6000 BC, Narva culture, 5300 BC, moose-hunters, hippophagi

‘horse-eaters’, raw-meat eaters, exposition on scaffolds, cults of the World

Egg, the World Tree

and the World Duck) →

Estonians/Aestii/Eesti, Aukštaitians, Ross’. Table 55. An analytic decomposition

of Baltic peoples The Baltids

were known to ancient Greeks as Hyperboreans and

flowed into the riverside territories of The

dominant ethnic layer among Baltids was formed by Yotvingo-Prussians, who came to the Baltic area as

bearers of the Corded Ware culture. Their travels traced earlier routes that

lined the Mesolithic wanderings of Littoralids to

the Urals and The cultural dominance of the

Indo-European Gotho-Frisians could not menace the

chronological priority of Gravettian immigrants,

who contributed the most populous layer of the Slavic and Lappic

substratum. Its impact was seen in satem shifts,

consonant palatalisation, nasal vowels, rich

diphthongisation, i-plurals and melodic

pitch accent. On the other hand, Uralic languages penetrated into the Baltic

morphology by incorporating Estonian perfect tenses and locative cases. Their

declinations included Uralic cases distinguishing essives,

adessives, allative, illatives and comitatives. |

|

Slavonic Polonids and Baltids Poles are classed as a Slavic nation but

their name derives from Bulgaroid Polonids. Their ancestors were the Ukrainian Polovtsy/Plavtsy, who are

erroneously classified as Turcoids, because they

fused with the surrounding Turcoid element. They

differed from Turcoid neighbours by their Tungusoid descent from Aurignacian

tribes with tepee tents and conical post-dwellings. Their core resided north

of the Euro-Tungids (also called Ladogans,

Baltids, Karelians, Hyperboreans; nomadic fishermen, lacustrine

lake-dwellers, pole-dwellings, tepee huts, Finnish steep-sloping chalets with

tepee-like gables, Lappish huts laevu and goahti, lakeside fishermen, acorn-eaters, ABO

group B, low frequencies of Y-hg C): North route 1:

Karelian Tungids: Karelians (Karjalabotn, Kirjaland),1 NW route:

Latvian Tungids: Baldayskaya

Range ® Baltinava ® Latgalians ®

Latvia ®

Curones2, W1

Polochan Tungids: Polochans, Poloczanians3 (at Polotsk,

Belarusia) ® Lithuanians ® Belostok ® Polans (also Polanes, Polanians, Polish Polanie

in the W2 Polonian Tungids: Połomia ®

Bolokhoveni4, W3

Euro-Tungids: Plone

® Belesane ® Ostfalen (Ostfalia) ® Westfalen ® W4 Euro-Tungids: Balti ( NW Pelasgids: Pelasgians (Pelasgiotes) ® Belegezites ( Table 56. A systematic

reclassification of eastern Mediterranids as pure Eteo-Tungids Extract from Pavel Bělíček: The Analytic

Survey of European Anthropology, Prague 2018, Table 46, p. 156-163 |

|